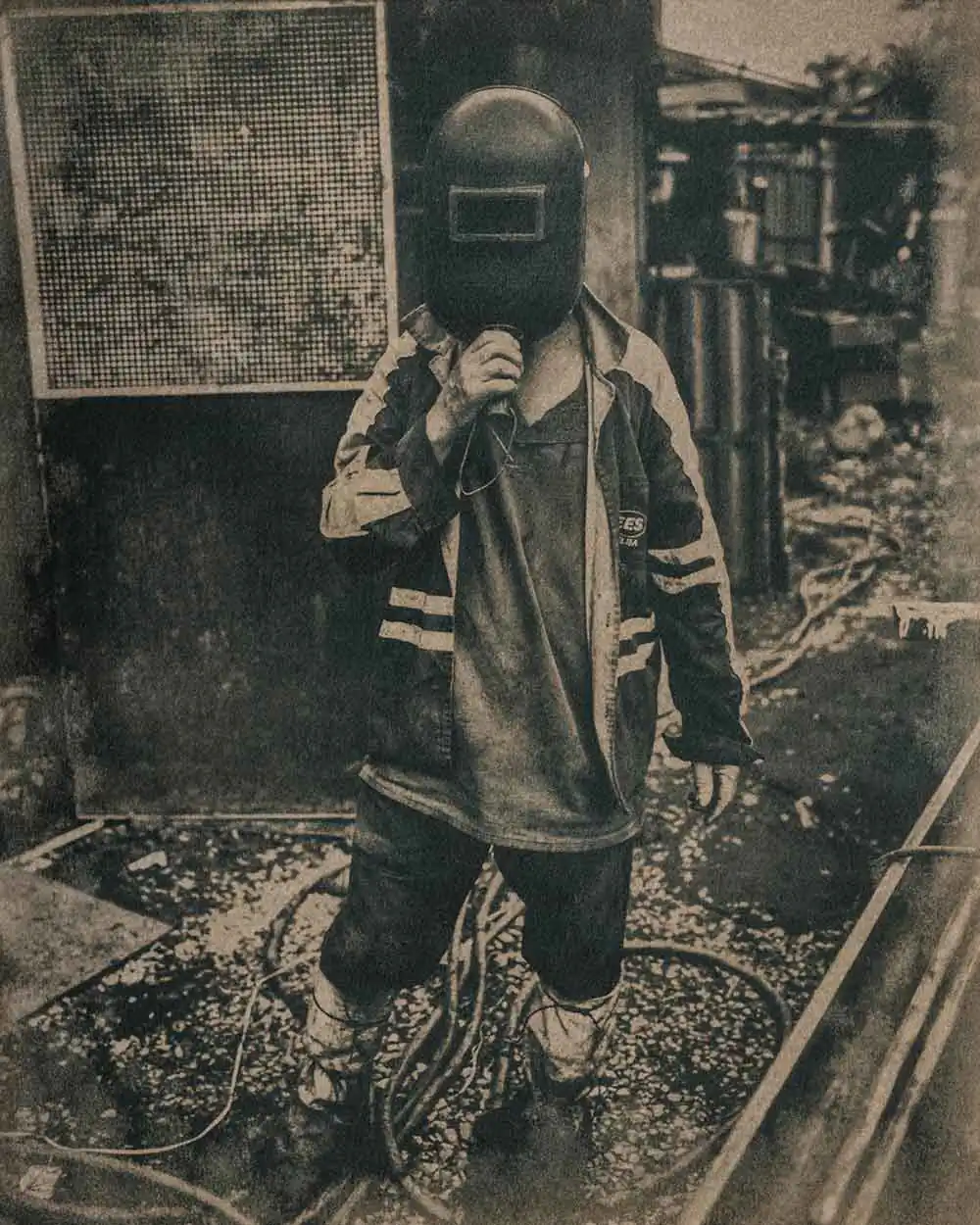

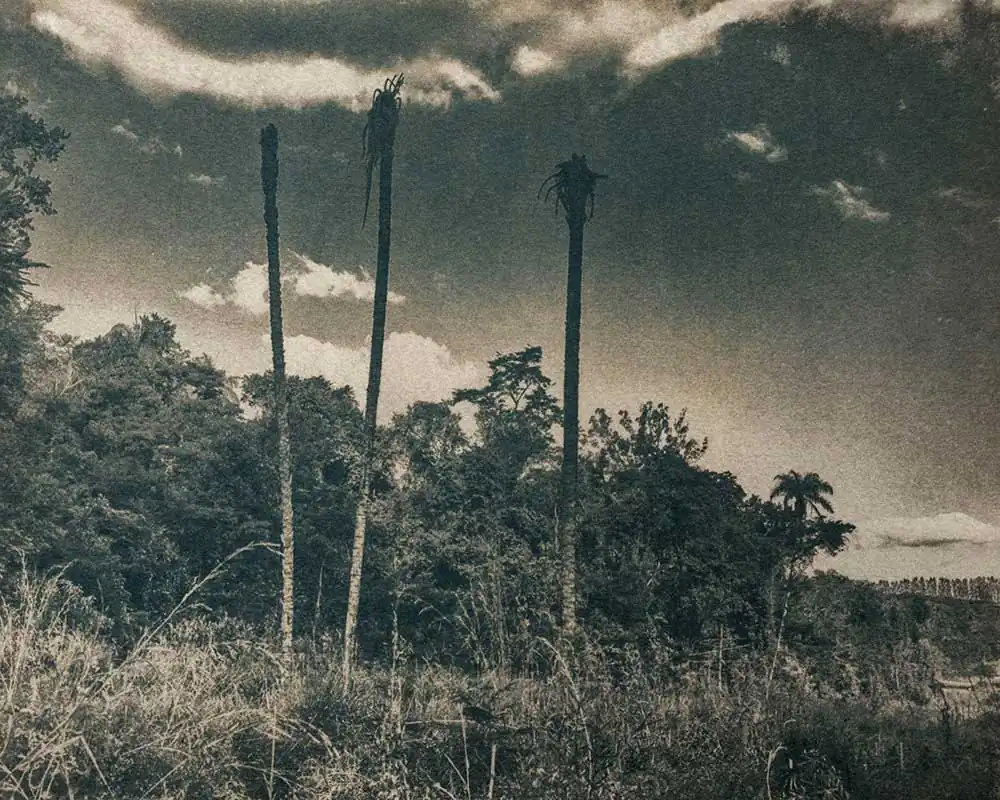

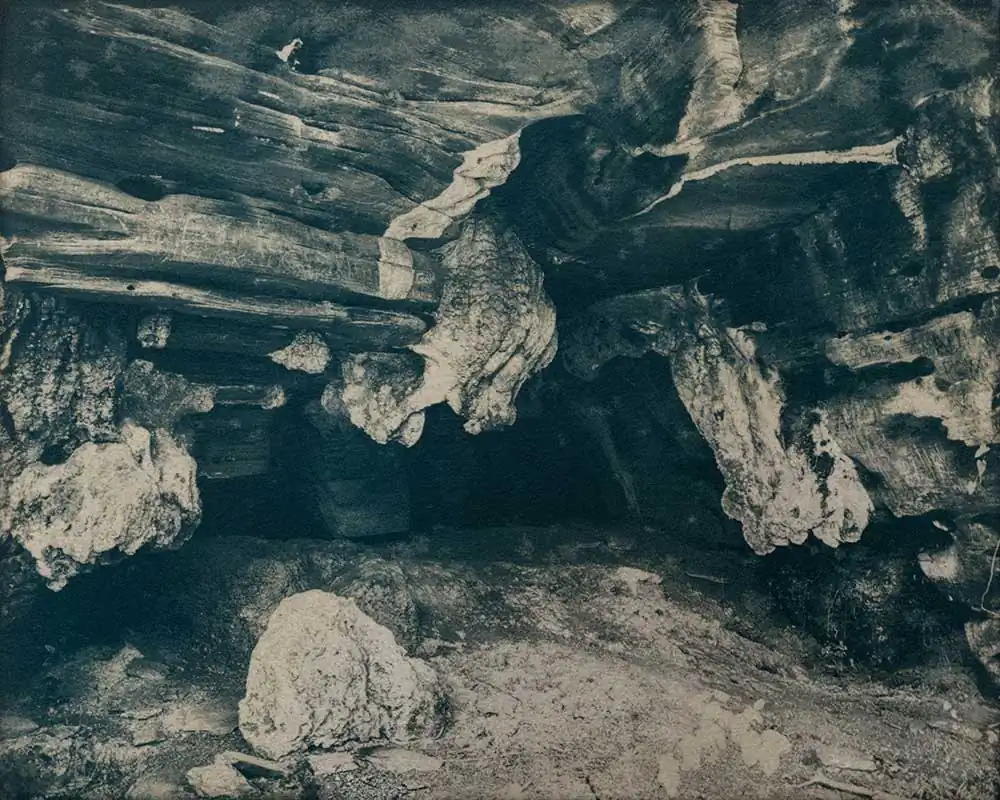

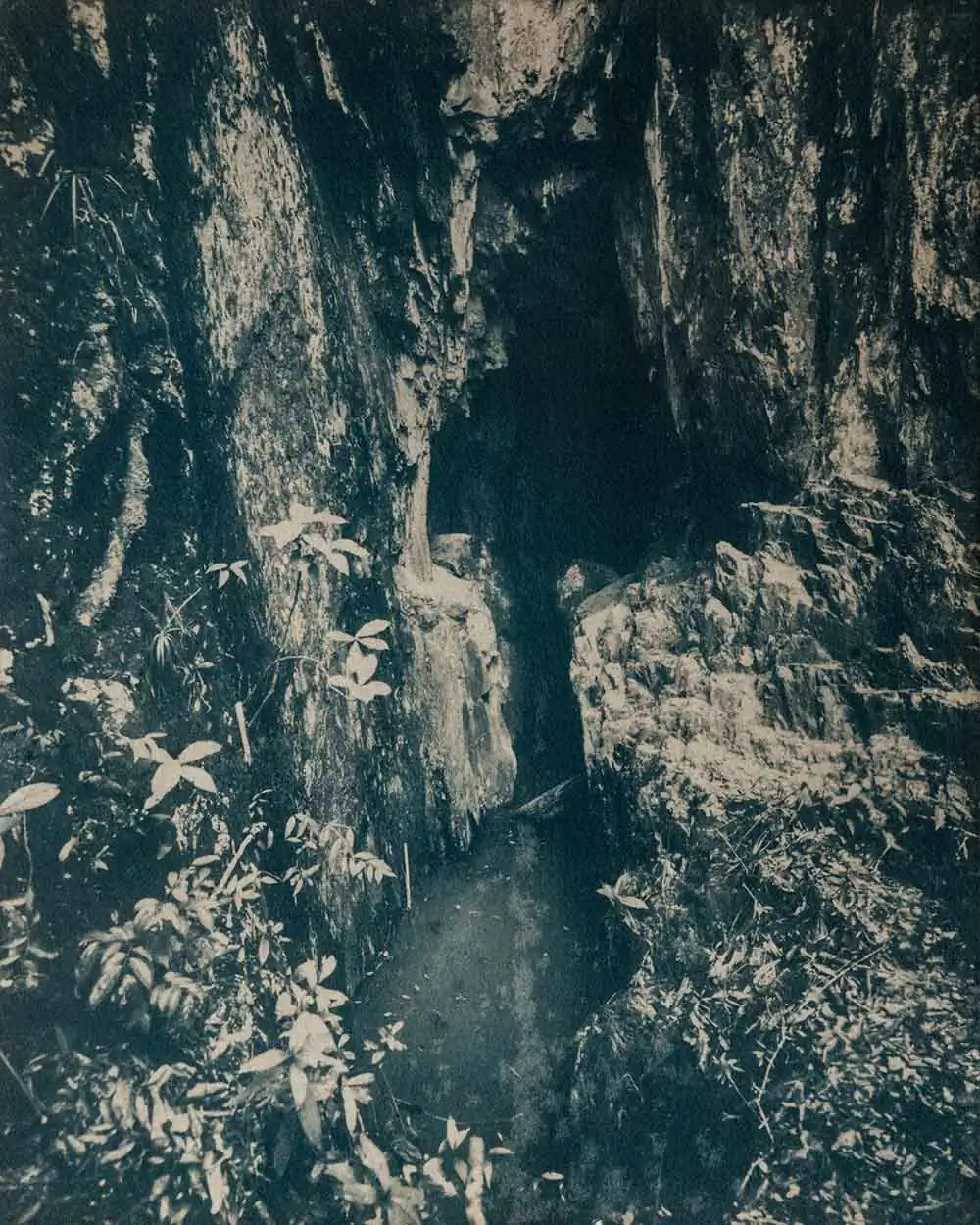

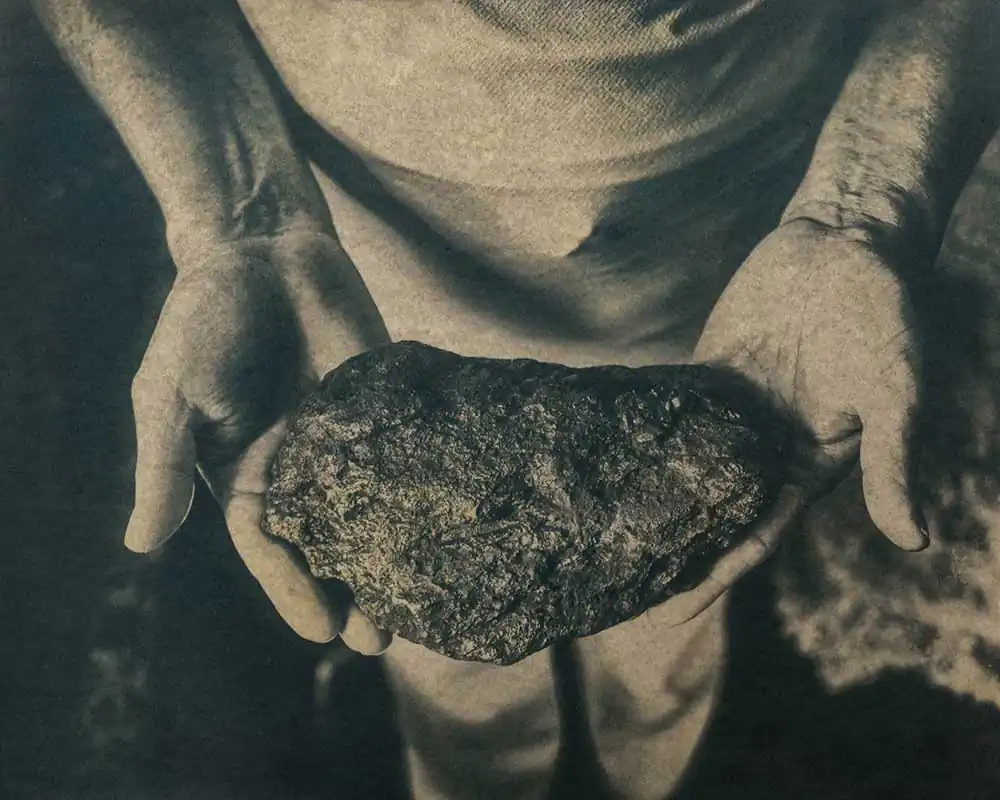

Origins is a body of work that attempts to scratch the surface of a rich but brutal history—a history of discovery and exploitation in the mineral-rich region of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

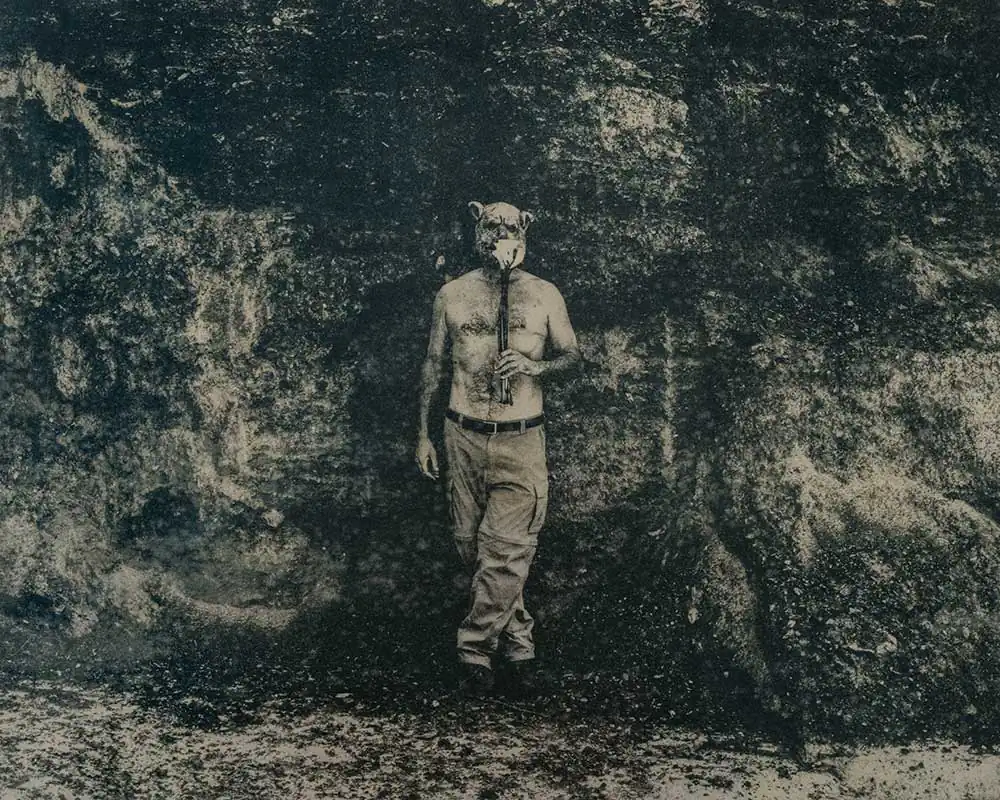

In Portuguese, the word exploração translates as both “exploitation” and “exploration,” a linguistic duality that captures the essence of this land’s story.

My work cannot begin to describe the wounds left on the earth and humanity by human avarice; I can only try to document the marks left behind.

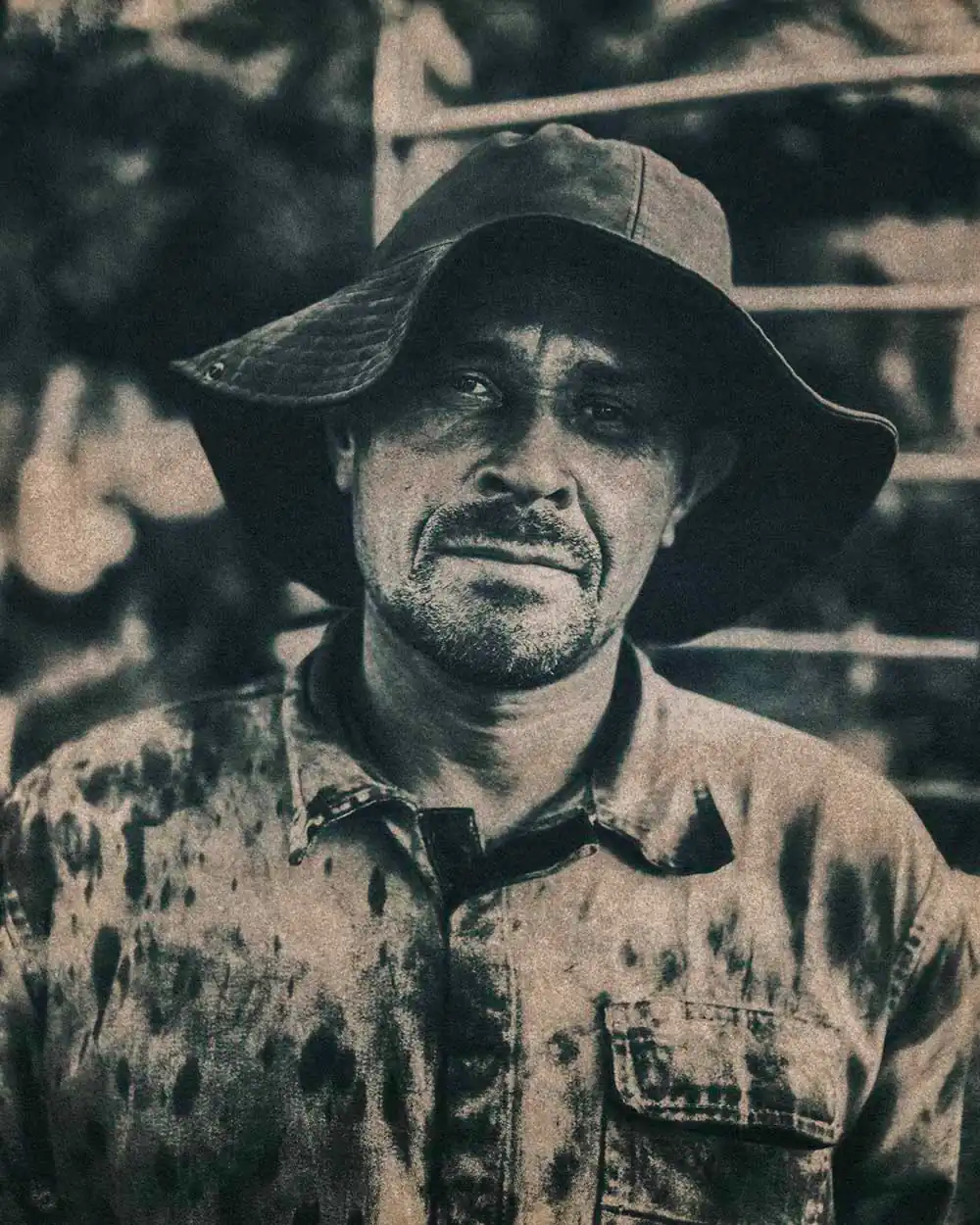

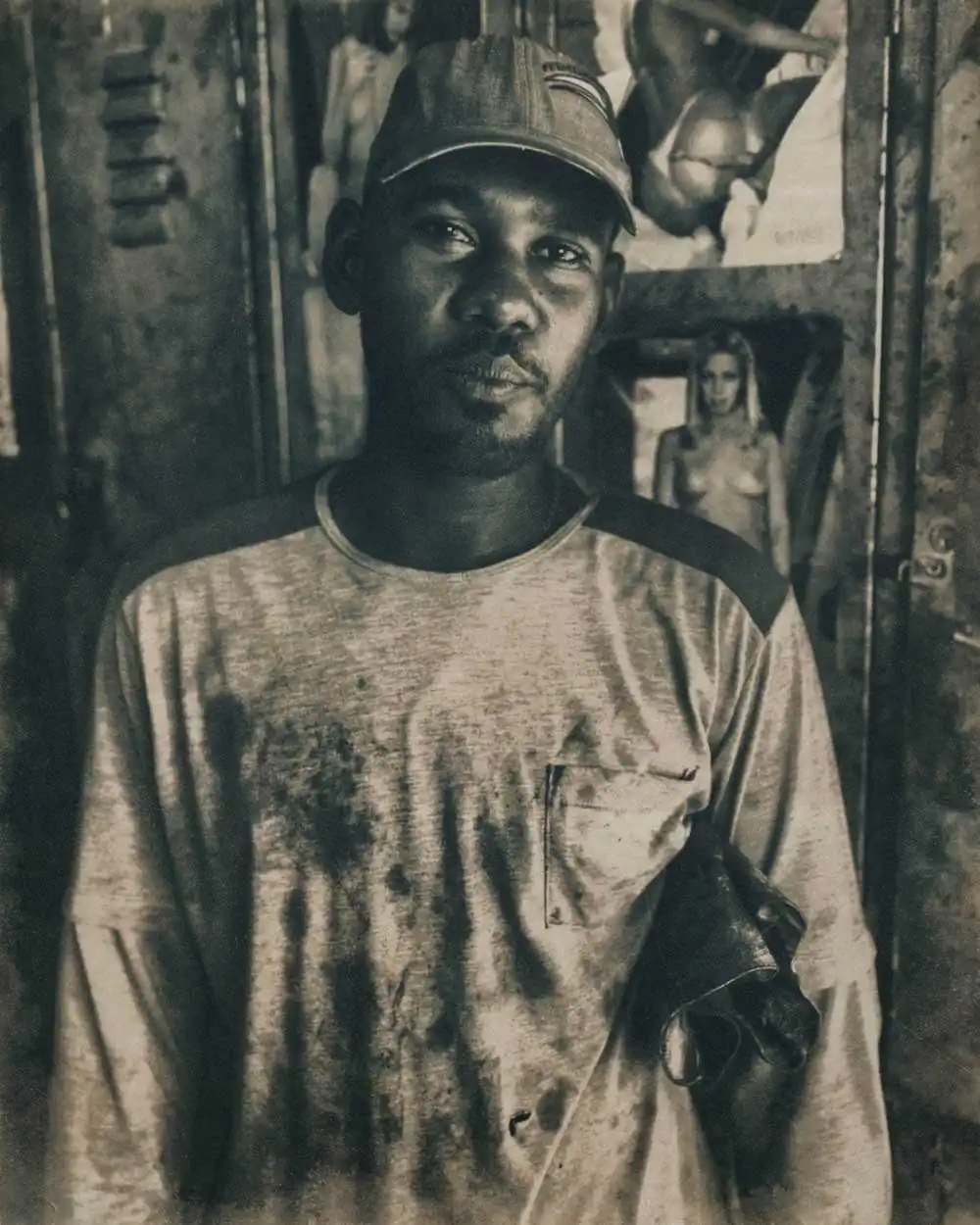

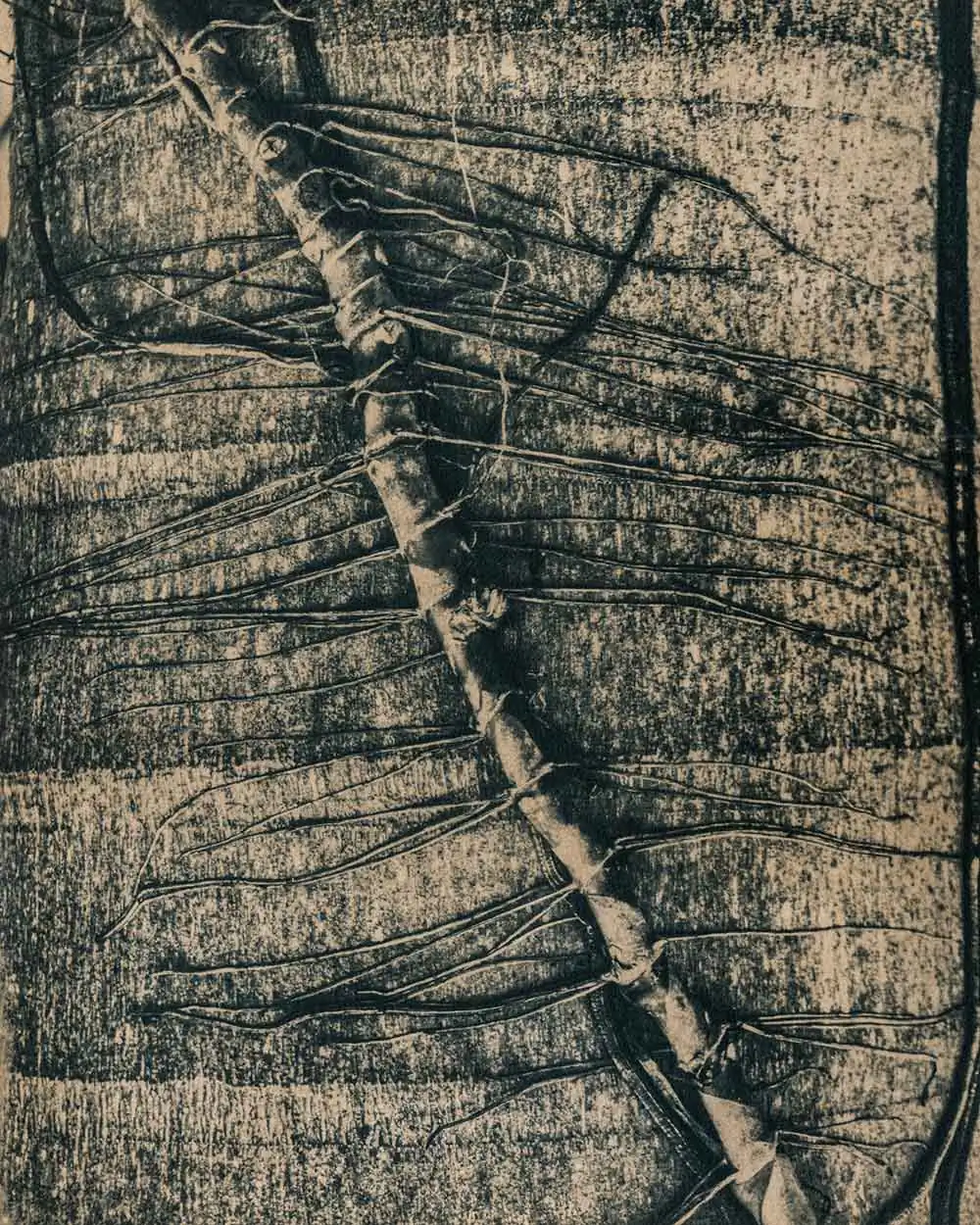

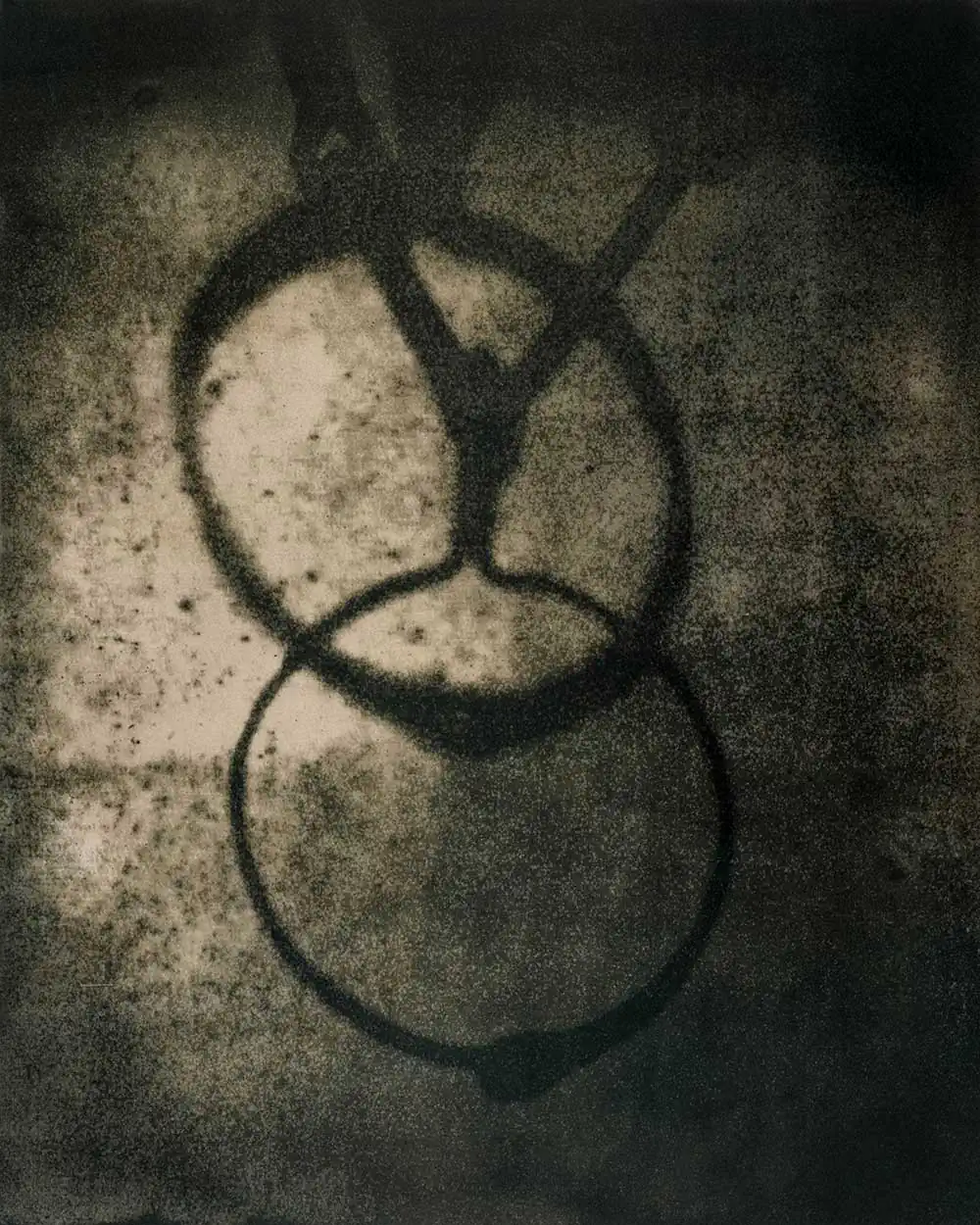

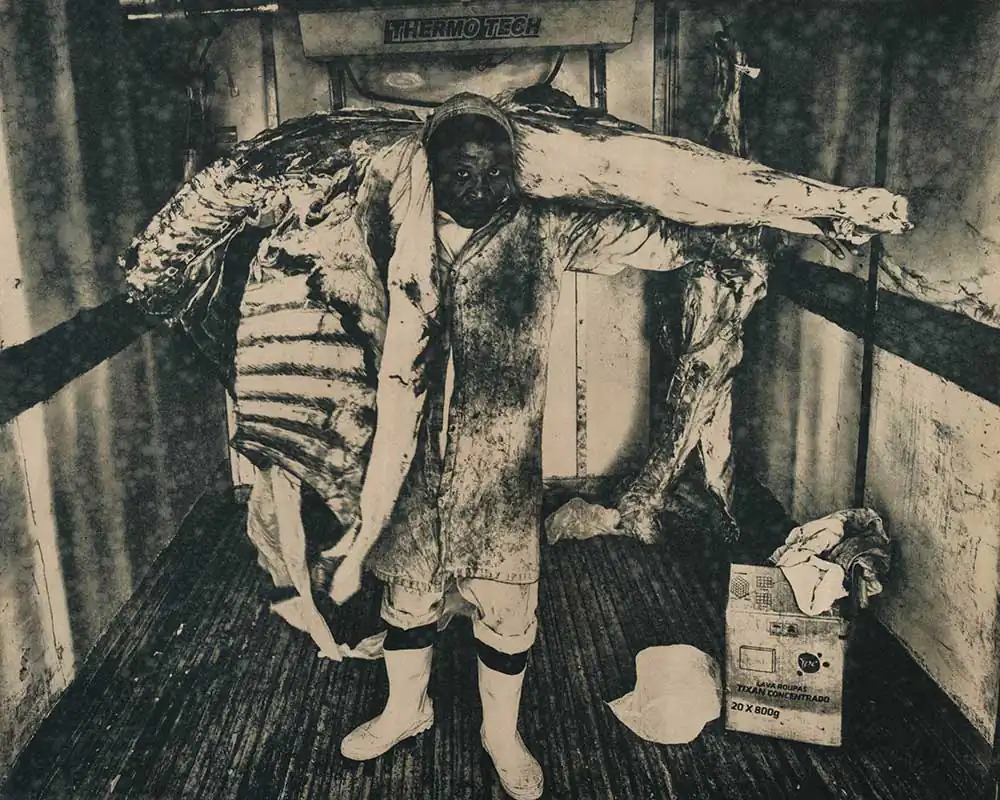

This project consists of coffee-stained cyanotypes, created using one of the first photographic processes developed in the mid-19th century. The principal active ingredient is iron salts, evoking the area known as the “Iron Triangle” where this imagery was captured. The state contains the world’s richest veins of iron ore, and mining comprises much of its economic activity today. Slavery was essential to the gold mining cycle that began in the 17th century and preceded the current iron industry. While Brazil abolished slavery in 1888—the last country in the Americas to do so—its systems and structures persist to this day.

The process of staining the images with coffee not only alters their color and tone but also references one of slavery’s primary activities in 19th-century Brazil: the harvesting of coffee beans. The coffee and iron salts used to render these images are themselves commodities still produced in the region, alongside gold, silver, and the exploitation of human labor. The staining process resonates with the idea of remnants. My work records both the reflections and shadows I perceive of this history and its direct evidence.

My work is concerned with recording the reflections and shadows of a history that remains opaque at best. As in my own country, the United States, it is a sordid story that has permeated society’s bedrock foundations. Capitalism, colonialism, and political systems were all created with explicit disregard for the human beings they commodified—people considered less valuable than the minerals they extracted to be sent back to Portugal.

In Brazil, the Estrada Real (Royal Road) extended from Paraty on the coast to Diamantina in the interior of Minas Gerais—a town named for its diamond discoveries and extraction. The Royal Road was a tool of supremacy designed to guarantee the flow of mineral wealth from Brazil to Portugal. Simultaneously, it was meant to limit Brazil’s potential by making it dependent on and subservient to Portugal. Despite its grandiose name, the Estrada Real was designed to choke Brazil’s ability to stand independently. The country was kept poorly educated, and all manufactured goods were meant to come from Portugal, with the intention of making Brazil a permanent vassal to the crown.

As both a historian and photographer, I am fascinated by this system of supremacy—its intricate mechanisms of control that people learned to live with. Those who held power became the elites, while those who toiled under their yoke became accustomed to what they could not change. The system was installed, and society grew around it, just as it did in the United States. The modern institutions of capitalism were being invented at the time, and they too accommodated themselves to the prevailing systems of supremacy.

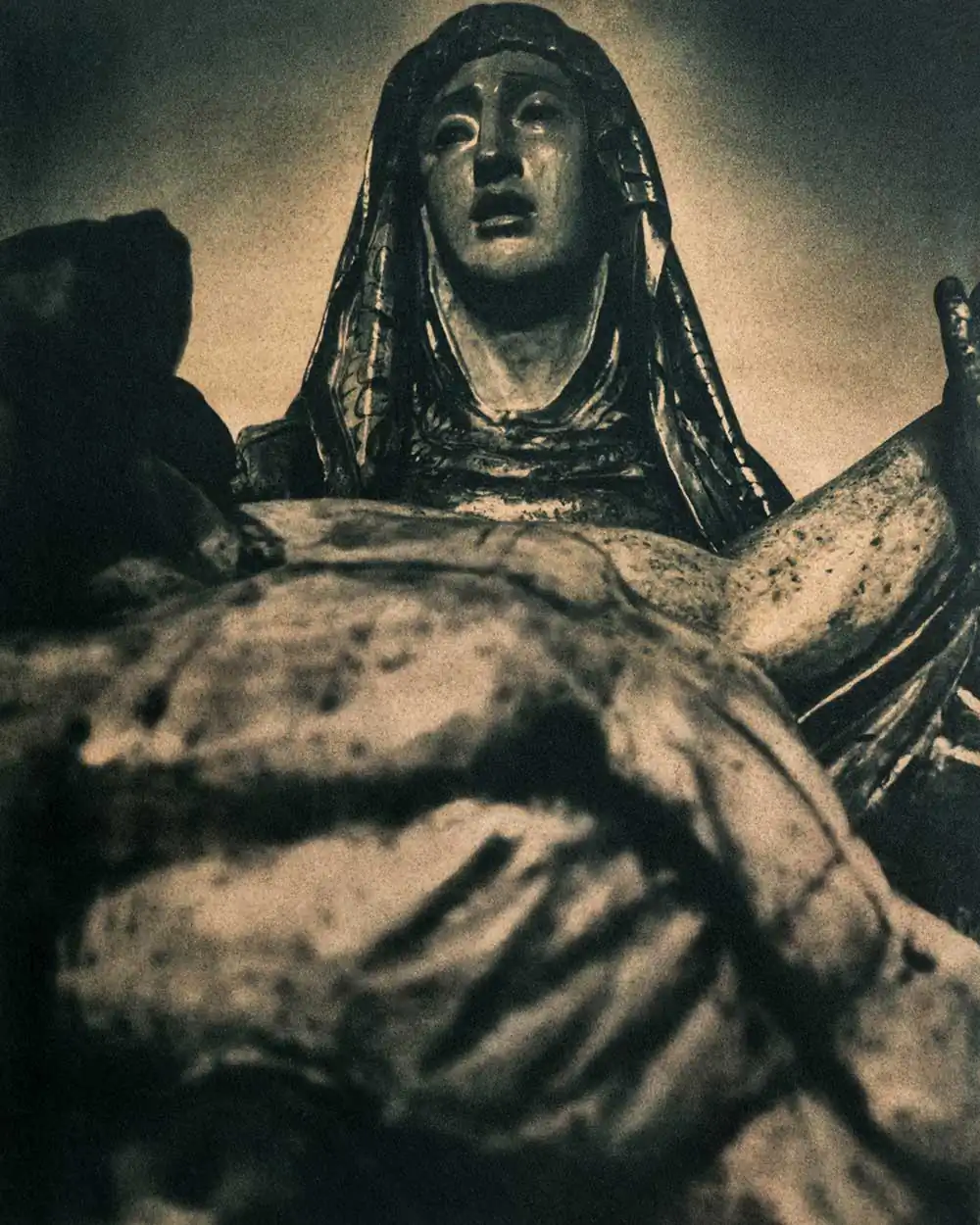

Despite these evil legacies, there is a bright side. The culture of the peoples who were part of this complex system exists vibrantly today. The incredible culture of colonial Brazil is exemplified by UNESCO World Heritage cities like Ouro Preto, Congonhas, and Diamantina—breathtaking in their beauty. Equally incredible is the culture that developed from the African peoples brought to mine the riches so desired by the Portuguese crown. Today, these places stand as monuments to a past built on ambition and avarice. [Official Website]