Photography emerged hand in hand with portraiture.

In the nineteenth century the new bourgeois class embraced the daguerreotype as a tool for preserving their likeness and achieving a kind of visual immortality.

Until then, accurate representations of the face had been limited to emperors and nobles through marble busts, engraved coins or oil paintings. The camera opened that privilege to many more people, and the flood of individual and family portraits showed that the medium was both a mirror of identity and a public statement of status.

Theory usually separates this practice into two threads: the portrait that highlights personal traits and the effigy that underlines social position. In reality the two often overlap. August Sander, for instance, documented professions and classes with near-anthropological rigor, while Nadar exalted the personality of writers and artists yet still revealed their cultural standing. Implicit in every frame lies the logic of inclusion and exclusion; whoever appears inside the rectangle defines themselves, while those outside are marked as different.

Family portraiture extends that logic. More than a simple document, it certifies blood ties and emotional bonds, displaying physical inheritance in a shared space and moment. Few photographers have chosen entire families as a central theme; Thomas Struth is a notable exception. Another, more contemporary and singular, is the South Korean photographer Byun Soon choel with his series on displaced families.

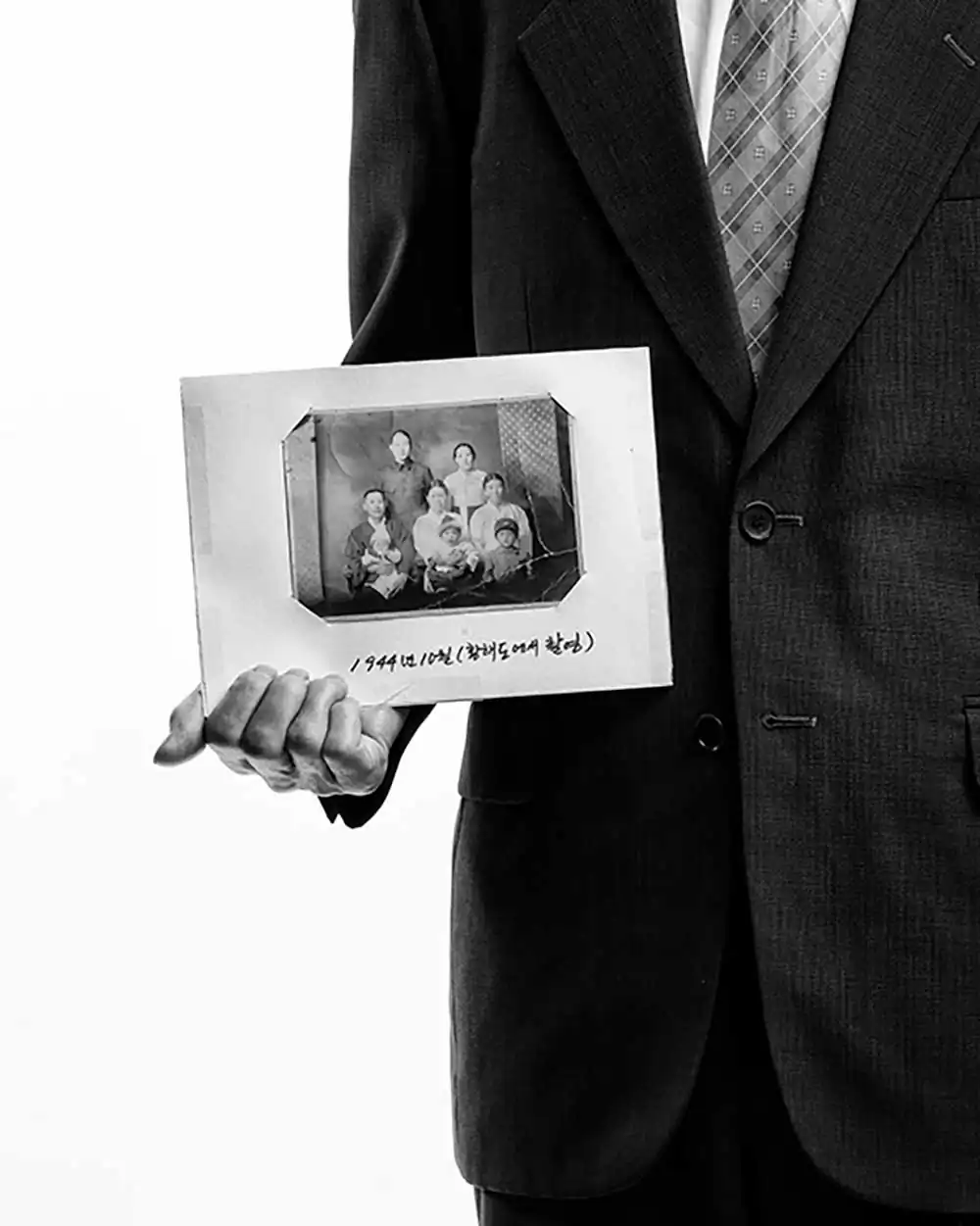

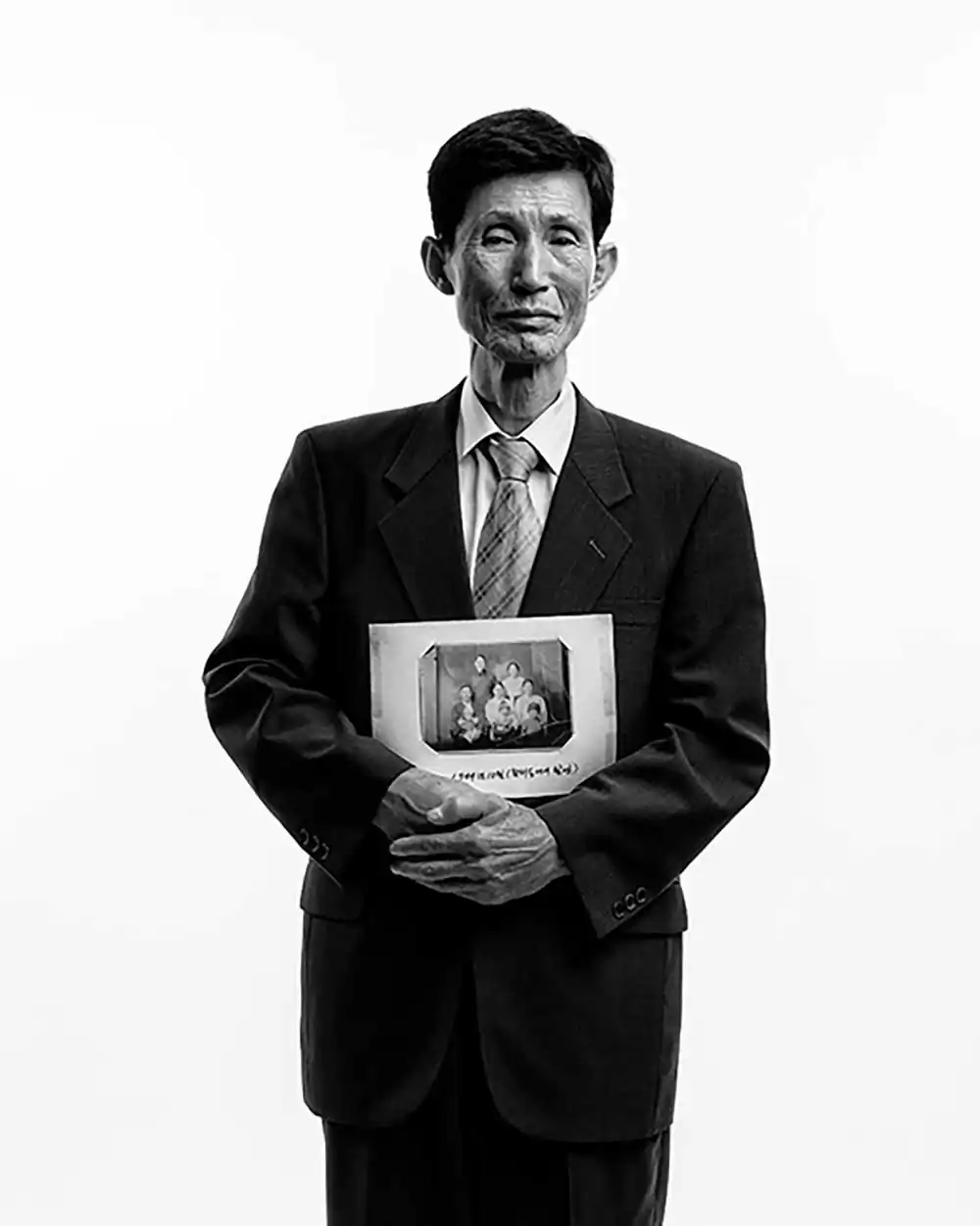

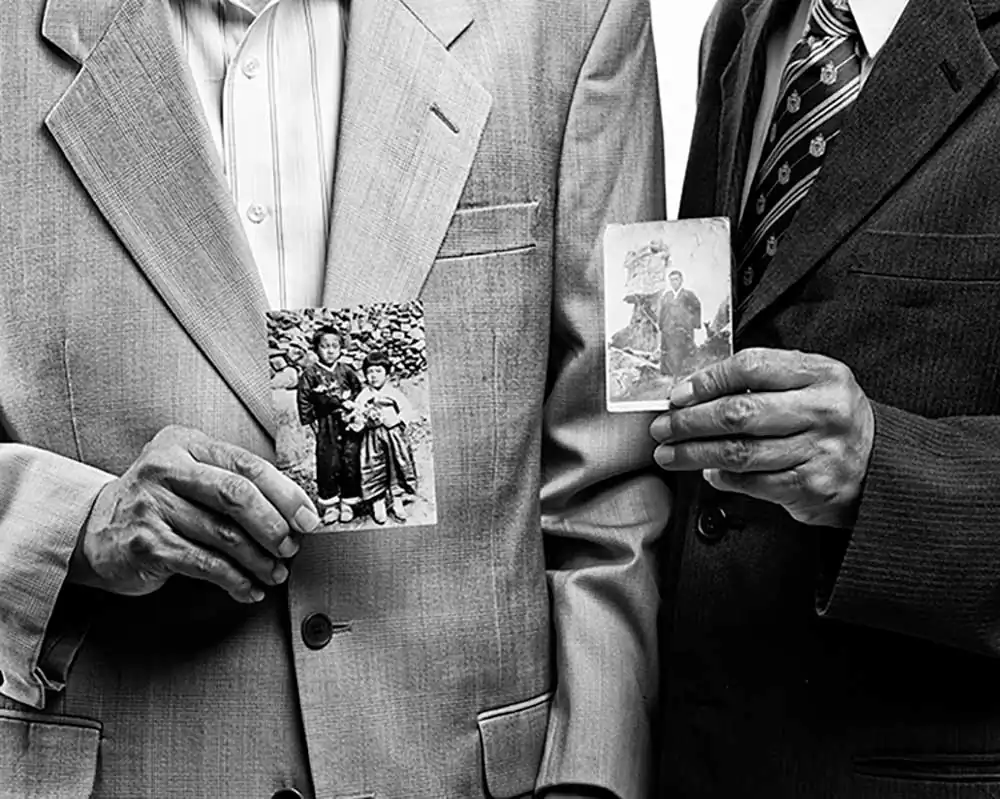

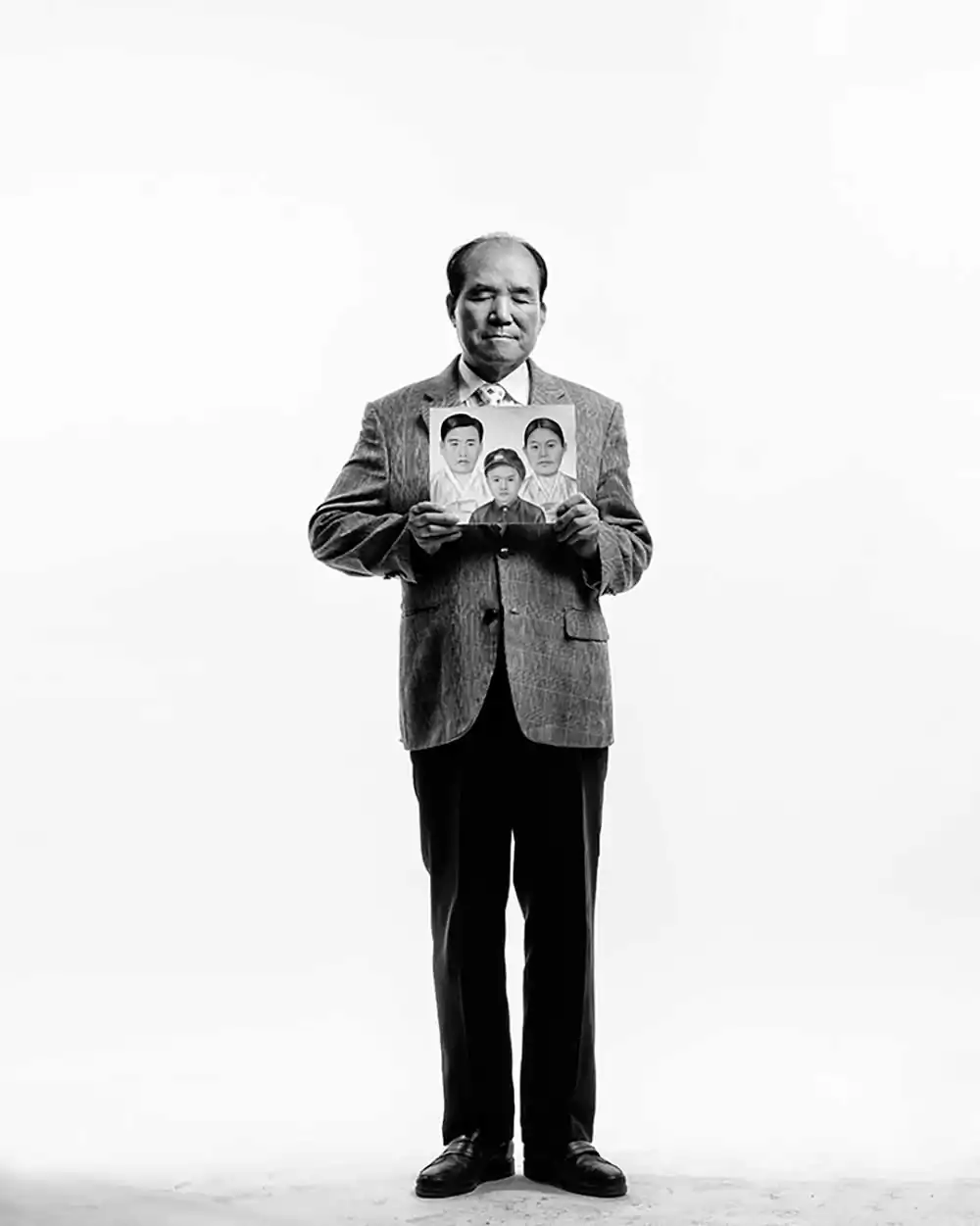

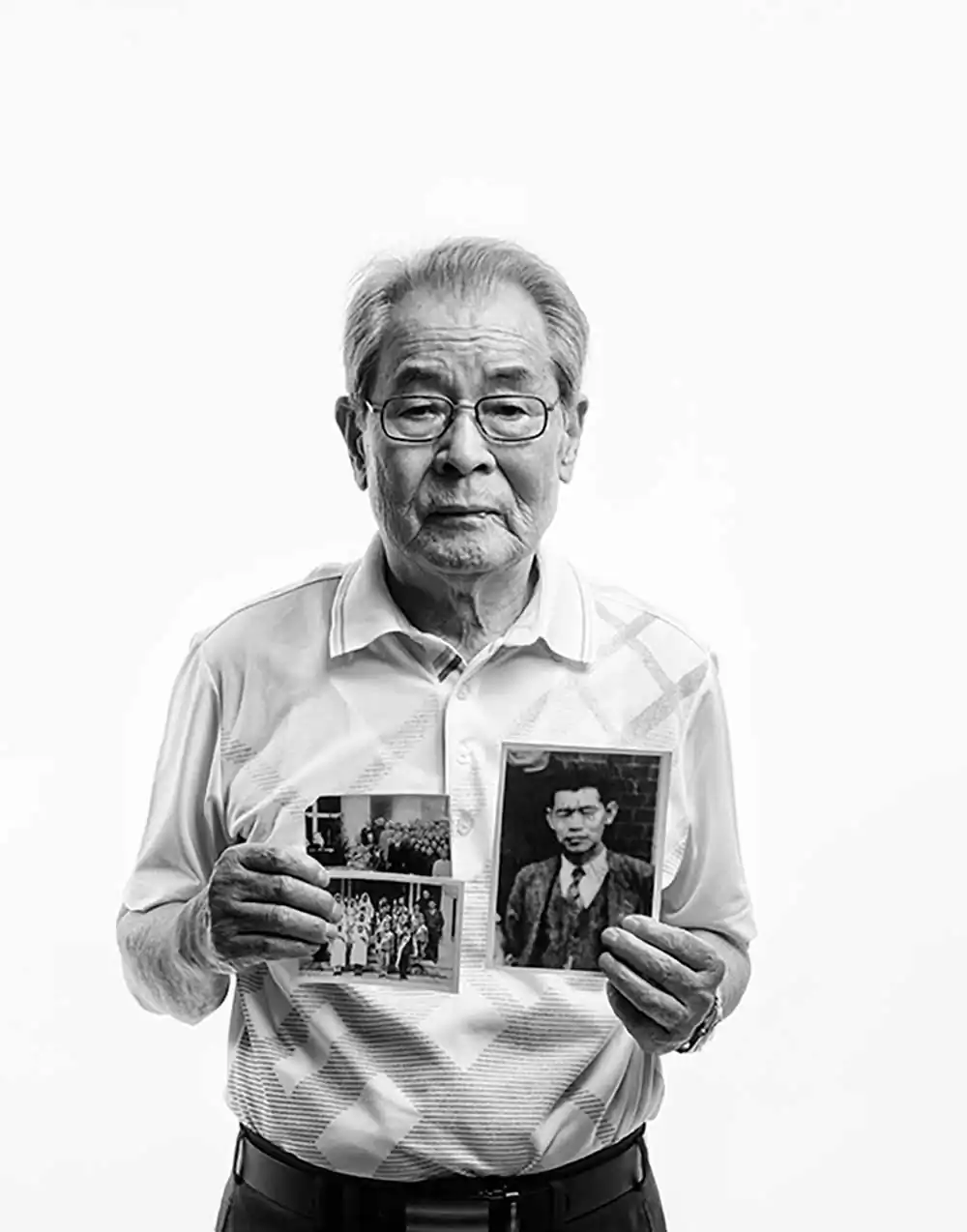

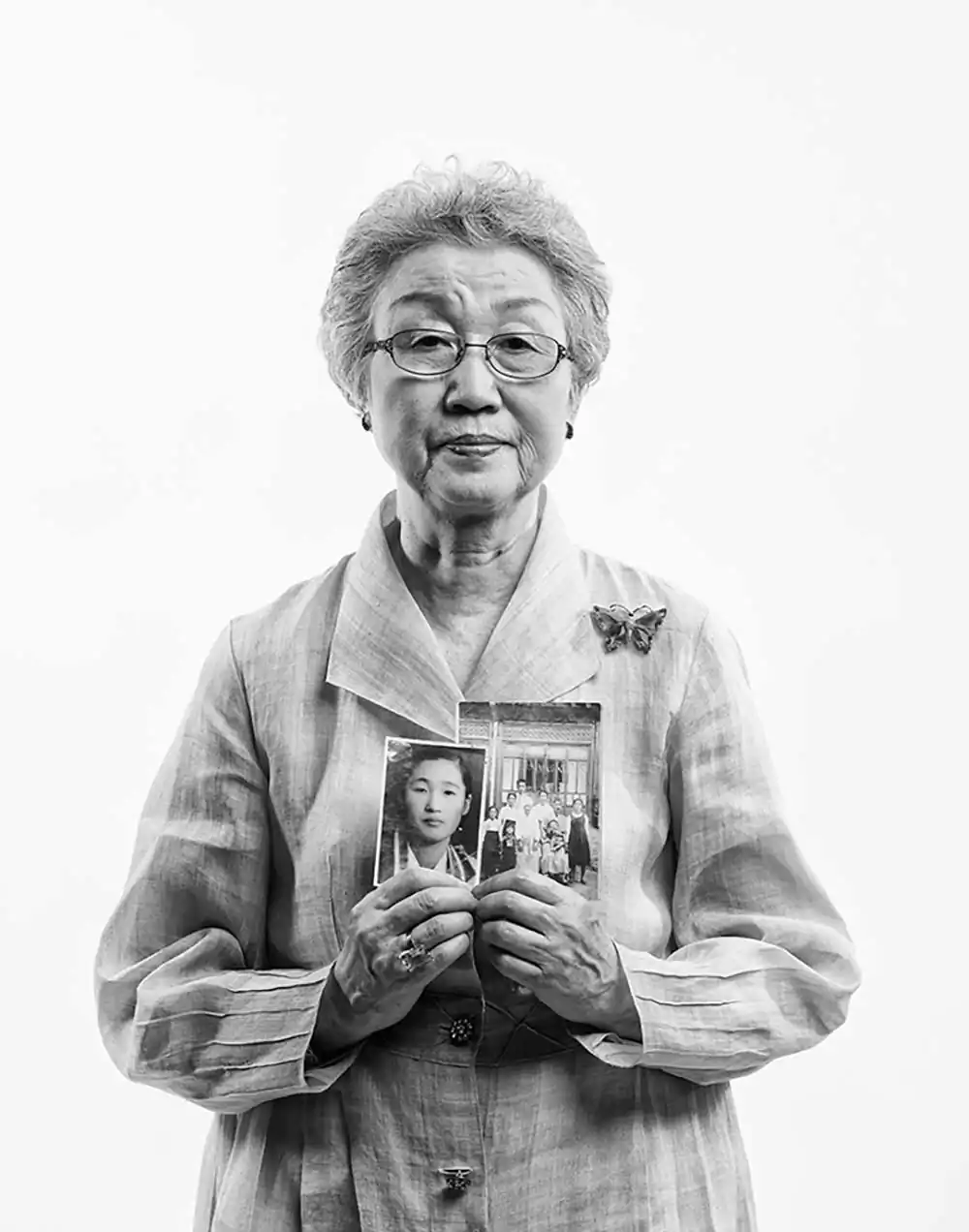

In Korea the term displaced refers to people who fled the North during the war and were permanently separated from relatives. Statistics differ, some sources exceed eight million when counting second and third generations, but the crucial fact is the rupture that only rare government-run events can temporarily bridge. Byun conceived a way to restore those bonds visually. After securing corporate backing and with help from the Red Cross, he contacted two thousand refugees eager to “meet” their loved ones again. Barely one percent still possessed photographs old enough to serve as raw material.

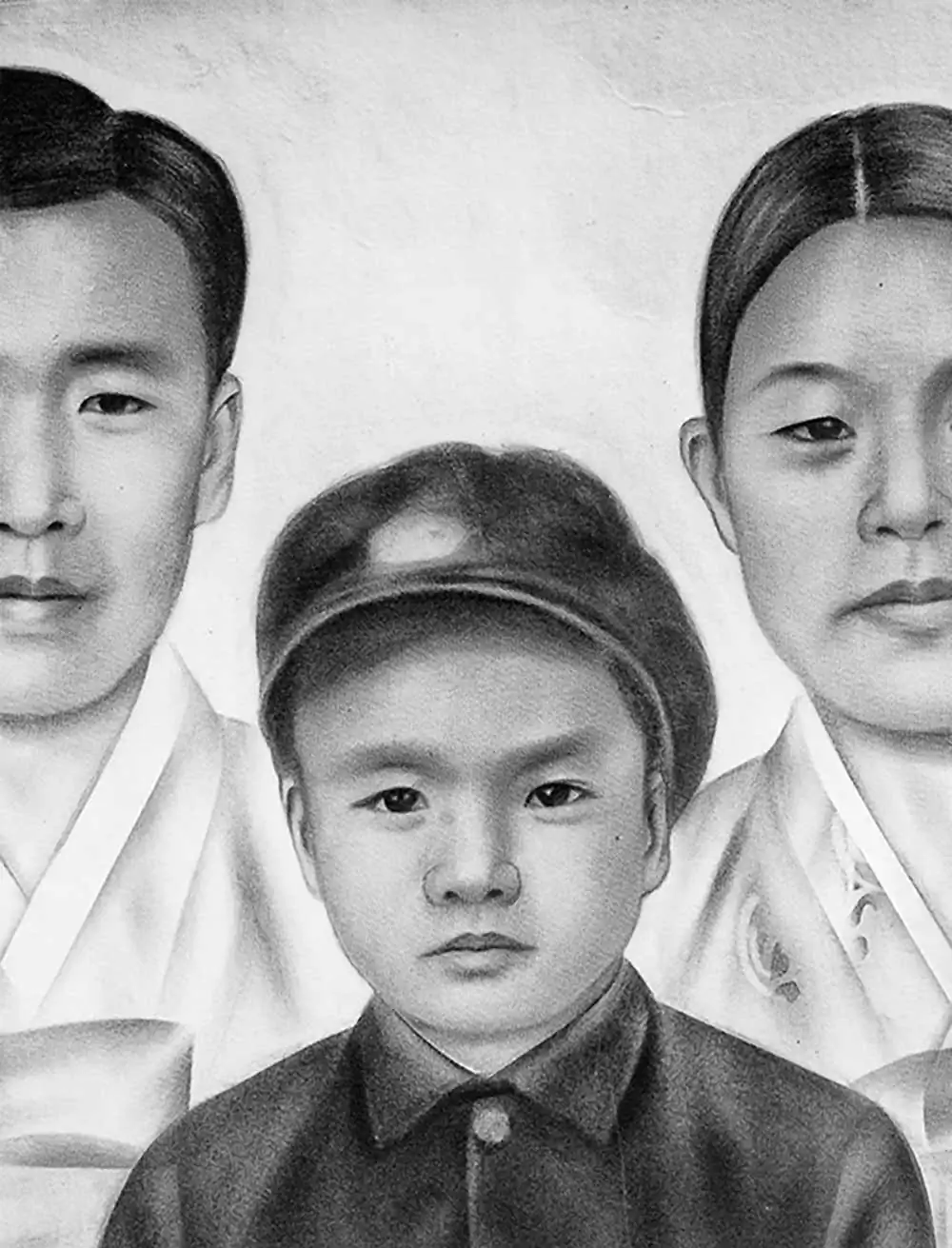

The project relied on the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, whose imaging lab created a 3D aging program in 2014 for missing-person cases. The software analyzes wrinkle volume, skin thickness and micro-expressions, then renders an aged version of each face with up to eighty percent accuracy. Byun paired those updated faces with bodies of studio models of the correct age, producing twenty-three composite portraits where parents, children and siblings divided by a militarized border stand together decades later.

The result is both moving and disconcerting. In the vocabulary of Vilém Flusser the pictures occupy a pataphysical space where virtual and real intermingle until they are hard to distinguish. For the refugees they operate as potent emotional surrogates. One participant visited the studio almost daily, explaining, “I cannot leave my father there alone.” The images reveal how photography in the digital age can transcend physical absence.

They also reopen basic questions about the medium. Once regarded as proof of reality, the photograph now becomes a device for manifesting a wished-for unreality. Flusser’s concept of the Techno-bild describes this fusion of bits and concrete life. Everyday culture often recognizes this power before art does, as seen in Korean subway ads for cosmetic surgery that present equally uncanny transformations.

Byun shoots his subjects head-on, honoring classical portrait conventions yet stripping away the indexical trace of light by inserting virtual elements. The people in his frames resemble what art critic Hal Foster calls “traumatized subjects” who replace the heroic modern individual. The historical wound of a divided Korea becomes visible in their digitally reassembled families, echoing motifs that have long interested the photographer, from his stark Interracial Couple series to the nationally beloved National Song Contest portraits.

Through this project photography recovers its primal role in memory and healing while expanding its technical and ontological limits. Future advances in artificial intelligence promise even more convincing reconstructions, raising new questions about authenticity, empathy and the essence of the image. Byun’s next chapter, and the next chapter of photography itself, will likely push further into that borderland where fact and longing intersect. [Official Website]