A photograph acquires something of the dignity which it ordinarily lacks when it ceases to be a reproduction of reality and shows us things that no longer exist.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time Vol. II, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower

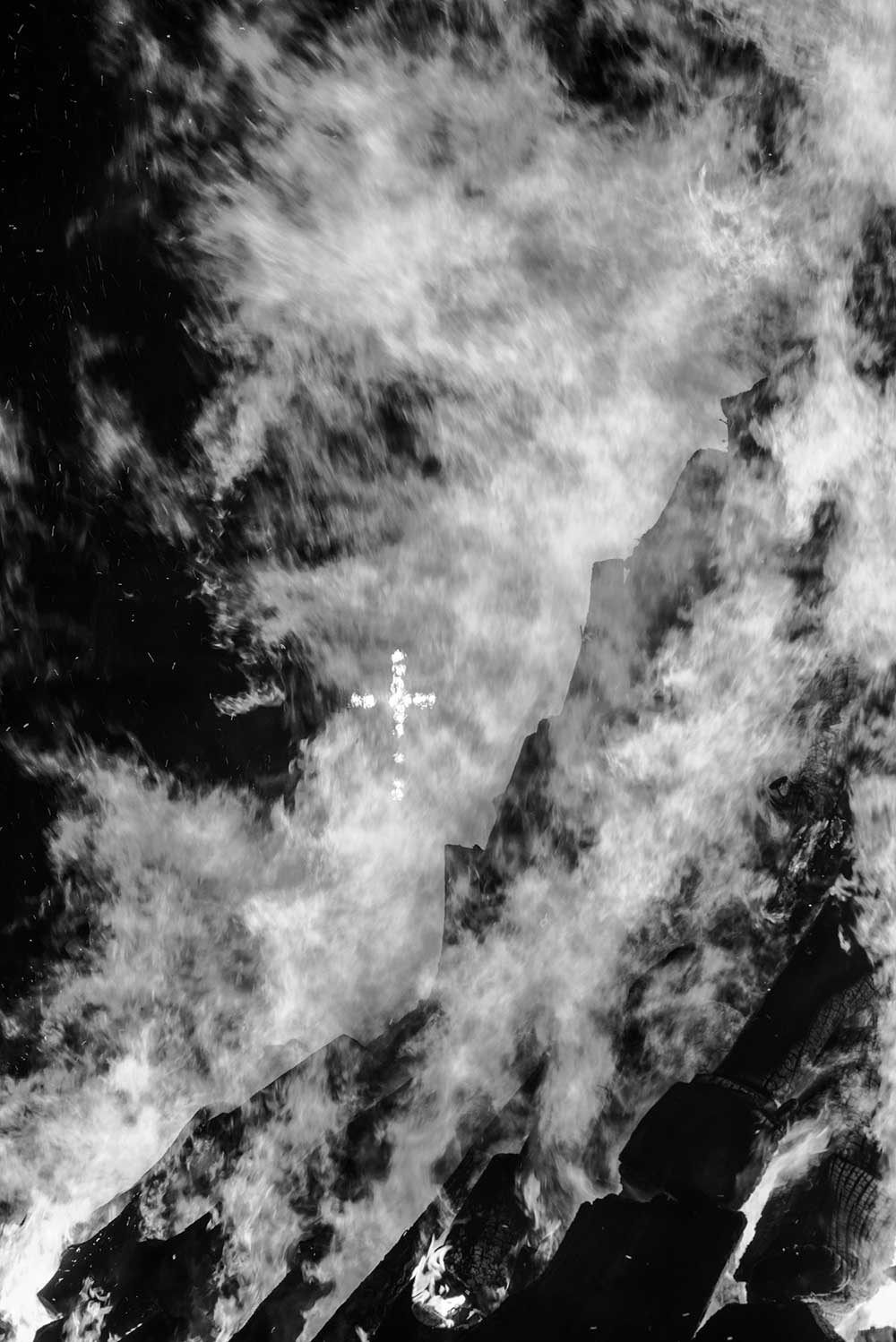

What if, in a diaphragmatic space located next to the passage cited in the exergue, it were precisely by reproducing reality that photography managed to show “things that no longer exist”? To a gaze that looks obliquely, as it were, at the photographic images in this volume, Gian Marco Sanna’s challenge with Paradise seems to be just this.

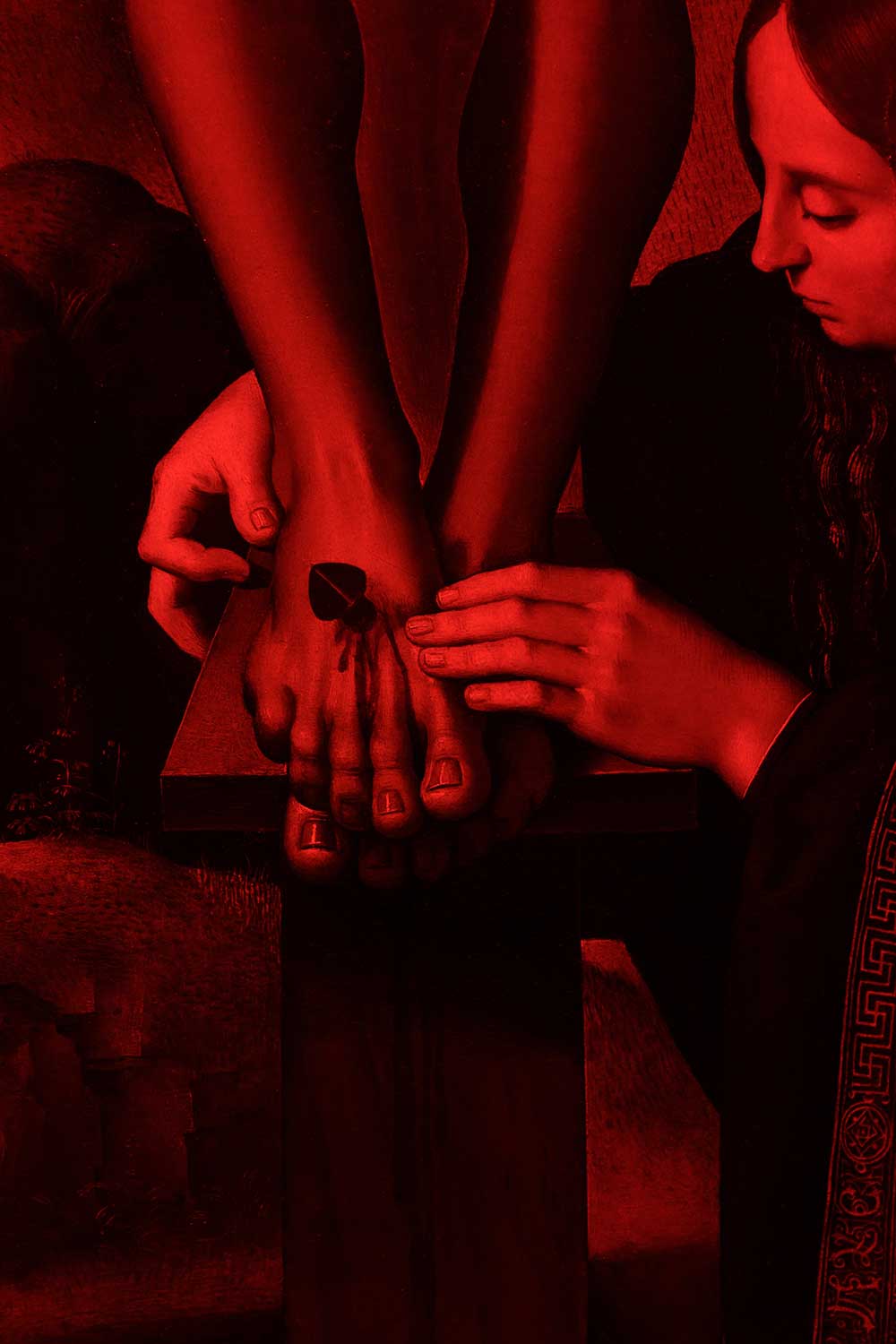

“Earth is paradise. Hell is not noticing it.” Sanna has often cited this apho- rism by Borges in various interviews as the seed from which Paradise began to germinate within him. Hence, the choice of the red filter by which the eye is overwhelmed when viewing the shots: i.e., to make a sign of the exhaustion and weariness of a planet where, from many quarters, it is said that ‘life’ cannot go on like this for long. Covering the image with a filter – to be provocative – is not, however, a gesture so unlike the one that has brought the ecosystem to the brink of the abyss (assuming, of course, that we are still on this side and not al- ready beyond it). However, by re-proposing such a gesture, Paradise lays its logic bare. In other words, it highlights the fact that the planet, over the time it has been inhabited by homo sapiens sapiens, has seen the filter of technical-linguistic paraphernalia placed between itself and the latter, which has led it ultimately to become a source from which to draw resources for purposes of endless ac- cumulation.

Without assuming Manichean positions on the matter, Paradise’s laying bare shows just this: that the relationship between the homo and ‘the world’ is always mediated by this or that technical device. And thus the very experience of the world, for the homo, can only open up – and the unpredictable scenarios that ensue unfold here – through something technical. This is what the ope- ning scenes of 2001: A Space Odyssey already clearly portrayed: the trouble, so to speak, begins when a bone is no longer merely what apparently remains of life, but becomes a tool that can violate it. The problem with technology is ‘all here’ – so to speak, given the space available – in its constituting a supplement to the non-immanence of the datum;1 in other words, in its representing the entirely human way of coming to terms with the fact that, however homo wants to put it, there seems to be no ‘natural order’ – a meaning – of things for him. We might mention in passing how it’s particularly remarkable that Paradise was born out of Sanna’s stay in Jordan. That is, it’s remarkable how a work like this originated in an area that has witnessed the emergence of the three monothei- sms. Each in its own way has laid claims to indicating this ‘natural’ order of the world.

Amid the folds of its photographic images, this is what Paradise seems to show. By reproducing reality, Sanna signals to a world that no longer exists. ‘Reproducing reality’: not in the tired and rehashed sense of its imitation: ‘re- production’ here should be understood as ‘representation’, i.e. the (re-)presen- tation of a reality that, as such, is presented, giving an image of itself. From this point of view, when not a mere shadow or reflection of the existent, the ima- ge always wrests the thing from its autistic self-presence. The image, in other words, is always violent. It contends with the things for their presence: “In the image, the thing is not content simply to be; the image shows that the thing is and how it is. The image is what takes the thing out of its simple presence and brings it to pres-ence […], turned toward the outside”.2 A sensible world, or- dered according to instances that are transcendent to it (e.g. God) or immanent to it (e.g. History, Progress) – a kosmos – prevents us from presenting this very ‘outside’ in which things are absolutely exposed in their presence, i.e. alongside – but this is a gap which, although infinitesimal, is abysmal – the signification that these instances deploy, in one way or another.

However, according to Sanna, it’s not a matter of crying over spilt milk; if anything, it’s a question of showing that such meaningfulness was the harbin- ger of a logic of the One against the Multiplicity, to which, instead, voice or rather image is given here. The shots of Paradise, in fact, in the space once occu- pied by the kosmos, leave room for the range of singular elements in which the experience of the world today is differentially articulated. It is by making the photographic image the site of exposure (a second-degree one, we might say) of this plural singularity that, at the same time, photography can show what would no longer exist – the kosmos indeed. Herein lies the above-mentioned potential to show things that no longer exist, while reproducing reality (in the sense explained previously). By reproducing this space of exposure of singula- rity to the other from itself – to an ‘outside’ within the world itself – Sanna’s shots seem to take, shall we say, leave of ‘cosmesis’.

Faces, X-rays, bodies of human and non-human animals, cars abandoned to the lushness of nature, caves that seem to become the mouths of ancestral monsters of the depths, statues more or less mutilated by time, desert scena- rios…: the compositional structure of Paradise comes across as a broad corpus of images that (like every corpus) – having no other compositional logic than that of the differential articulation of its constituent parts – exposes the gaze not simply to this or that subject depicted. Unlike vision, the gaze is unfamiliar with objects or, phenomenologically, with ‘aspects’ of them. The gaze has a relation to the world as such, as an exhibition of singularities of which it is made up. This is why it’s difficult – if not impossible – to ‘look’ without this (or in French, as one would say with all its ambiguity: ça), in turn, affecting me.3 For it’s this reticulum that in turn – and perhaps even prior to any gaze – has already looked back at me.

It is no coincidence, then, that the subject we find at the close of the volu- me is portrayed from behind. This Rückenfigur, turning its back on the viewer, offers an opening for dialogue between the iconic and the extra-iconic space, inviting the viewer to transgress, to cross the threshold between the image and the place of the observer.4 From the extra[1]iconic ‘outside’ of the image, this transit – from the same to the same5 – gives access to nothing but the ‘outside’ in which and of which the ‘world’ itself is made up (again, a ‘cosmesis’ or perhaps an ‘a-cosmesis’).

1 See J.-L. Nancy, A Finite Thinking, edited by S. Sparks, Stanford University Press, Stanford 2003. 2 J.-L. Nancy, Image and Violence, in Id., The Ground of the Image, trans. by J. Fort, Fordham University Press, New York 2005, p. 21.

See J.-L. Nancy, The Subject and the Portrait, in Id., Portrait, trans. by S. Clift, S. Sparks, Fordham University Press, New York 2018.

4 On this issue, see A. Pinotti, Alla soglia dell’immagine. Da Narciso alla realtà virtuale, Einaudi, Turin 2021. 5 See M. Perniola, Transiti. Come si va dallo stesso allo stesso, Cappelli, Bologna 1985; Ritual thinking: sexuality, death, world, eng. trans. forewarded by H. J. Silverman, Humanity Books, New York 2001.

About Gian Marco Sanna

Gian Marco Sanna, born in Rome in 1993, is a multifaceted individual known for his contributions to the world of photography and art. He serves as the curator for Discarded Magazine and is a co-founder of the esteemed collective L.I.S.A.

Gian Marco’s journey in photography began in 2012 when he enrolled at the Roman School of Photography in Rome. Over the course of three years (2012-2015), he honed his skills, mastering both analogue and digital photography techniques. His passion for photography led him to the D.O.O.R. Academy in 2015, where he delved into the realm of documentary photography, pushing the boundaries of his craft.

From 2015 to 2017, Gian Marco immersed himself in the challenging environment of Malagrotta in Rome, home to Europe’s largest landfill. This experience undoubtedly left an indelible mark on his perspective and artistry. In 2016, he co-founded the L.I.S.A. collective, a platform that would go on to showcase groundbreaking photographic work.

In 2017, Gian Marco’s dedication paid off when the prestigious publishing house Urbanautica published his first book, “Malagrotta.” This significant accomplishment brought his work to international attention, with the book being presented at renowned events like Paris Photo at Mi Galerie in Paris and Fotofever in 2019. Additionally, the project found a home in various exhibitions, including those at 001 Gallery in Rome, Gallery Lombardi Arte in Siena, RiBella Art gallery in Viterbo (as part of the Caffeina Event), and Officine fotografiche in Milan. The “Malagrotta” project was also recognized with the Bi foto Prize and earned finalist positions in the Premio Marco Pesaresi 2018, Premio Voglino 2018, and the Emerging Talents Contest in 2018.

In September 2019, Gian Marco published his second work, “AGARTHI,” in collaboration with the publisher Penisola Edizioni. This project, which he had diligently worked on for five years, focused on Lake Bolsena. “AGARTHI” gained international recognition through exhibitions at various prestigious venues, including the Slovak Union of Visual Arts in Bratislava, MIA photo Fair in Milan, Prague photo festival, Cascina Farsetti Art in Rome, Parallel Voices 2020 in Greece, and the Gibellina PhotoRoad in Sicily.

Gian Marco’s talent was further acknowledged when two of his prints were selected to become part of the collection of Fondazione Orestiadi in Gibellina. His “AGARTHI” project also earned him the esteemed Parallel Voices 2020 award at the Photometria Festival in Greece.

Beyond his personal projects, Gian Marco has contributed his photographic expertise to numerous documentary magazines, further establishing his reputation as a versatile and accomplished photographer. His journey is a testament to his dedication to the art of photography and his commitment to shedding light on diverse subjects through his lens.[Official Website]