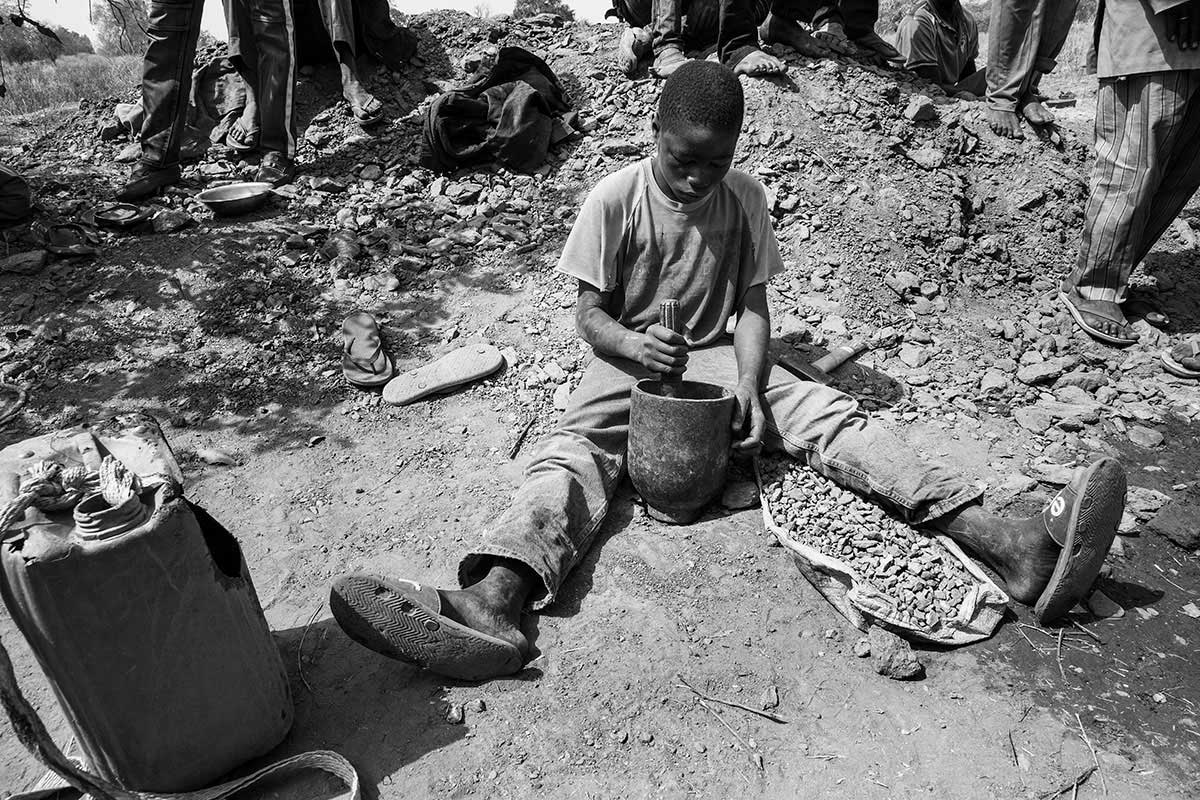

It is a dark world that millions of people are forced to work in, made of mines, dust and fear. Characterized by oppression, violence and trampled human rights; where the presence of enormous deposits of minerals transform into a curse for the people through the illegality caused by games of power and corrupt economies.

Black World is a long term project, started in 2012 and still in progress, focuses on realities in several countries with different kind of illegally extracted minerals.

In India, where the population of Bokohapadi is forced to steal its own coal found underground. This, because of industrial-scaled extraction projects run by government-aided companies, categorically without acknowledging or compensating the rightful owners of the land.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the words “Republic» and “Democratic» sound like the countless scars inflicted on its civil population, politics is administered on the basis of corruption and favoritism. A country where the absence of government, the division of power between different military groups and the intrusion of shameless and unethical foreign interests have caused a complete military arming of the economy and a real marketing of violence. In this chaos the natural resources, particularly coltan, become oxygen for the smouldering embers of war.

In Colombia, in a remote area of Antioquia, a community of gold miners has been struggling to fight for its own existence for years, asking the government to legalize the mine. This request amidst the dangers of working underground with inadequate equipment and under definite threat of being killed by paramilitary groups.

In Burkina Faso, where the search for gold is a survival activity, carried out without any protections in saturated dust environments, and where accidents, given the constant danger that the walls collapse, are on the agenda.

In Philippines, where tax on extractions are very high and people risks everday their life inside tunnel full of water.

Used primarily for cooking, heating, and to earn a little money by selling it, the coal monopolizes every single activity of Bokahapadi’s inhabitants.

Everything else is not important, including school education.

The only light is by torches attached to the miners’ helmets. There is only one way to enter the extraction zone. There aren’t any alternative safety exits. A sudden flooding in March 2015 caused the death of eight miners.