In Mongolia to the discovery of the last reindeer Dukha men and shamanic rituals. Mongolia is most impressive landscape with a strong spirituality.

We start from the tales of the conquests by Genghis Khan and his valiant warriors and then we move on to the beauty that only nature can constantly give. A place where the ability to adapt and a certain mental openness are required because a journey within this land is something sensational.

The beauty of these lands is still intact, the views are stunning and the scenarios that are presented are unique. Excluding the chaotic reality of the capital Ulan Batoor and thus immersing yourself in the desolate lands of northern Mongolia, the sensations of peace but also of loneliness and bewilderment envelop you to the point of inducing your own state of mind to merge solely with nature.

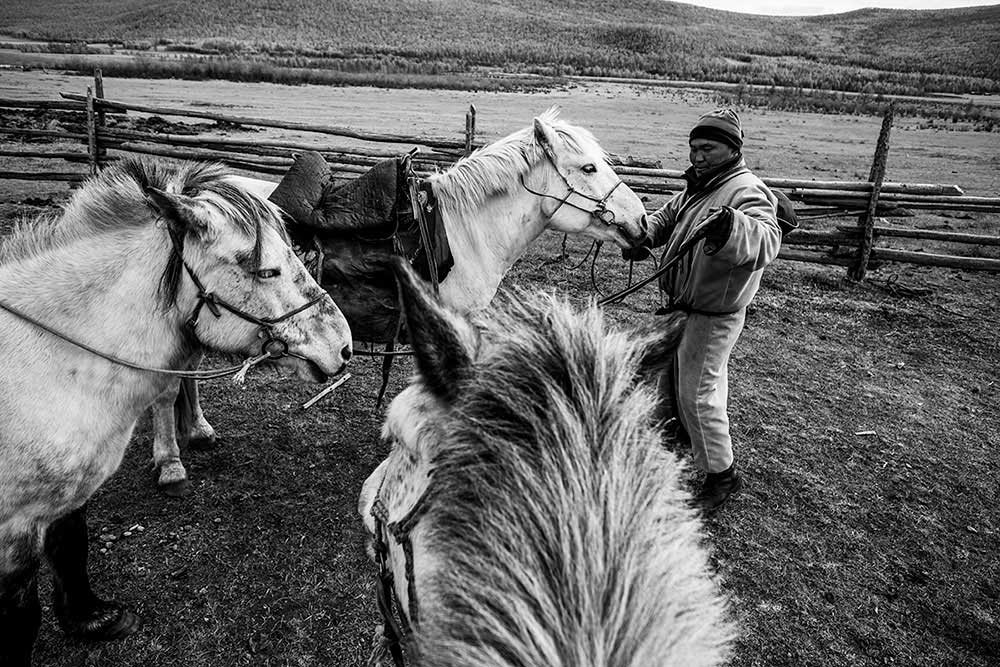

Here it is still possible to have an idea of the relationship between man and nature, of mutual respect and the concept of the common good. Not so far from the Mongolia – Russia border, there are still small villages in the middle of the taiga. Here live the Dukha, the last group of nomadic reindeer shepherds present in Mongolia. The Dukhas develop their economy and their lifestyle around the reindeer, maintaining and protecting them.

Originating in Russia, the Dukha (or Tsaatan in the Mongol language) are more similar to the Sami – the reindeer herders who live in the Scandinavian peninsula, commonly recognized as Lapps – than to the Mongolians of the steppe. The nomadic shepherds move with the ‘ortz’, inverted cone-shaped tents, similar to the tepees of the ancient Native Americans, following the reindeer cycles: in fact these animals cannot live in the steppe or along the valleys, where the temperatures are really tall; the only condition that allows them to live is in the north of Mongolia. The Dukhas live in this context throughout the year with temperatures ranging between – 40 ° and -50 °, surviving thanks to hunting and taming.

The Dukha tribe is endangered, and the remaining population today is only 44 families (about 200-400 people). They moved from Russia to Mongolian territory towards the end of World War II and tell of how they created many positive ties with the Mongol state.

Never moving from the taiga, they remained a separate group, compared to the inhabitants at the bottom of the valley or in the steppe, and are distinguished by their great knowledge of the territory. Their faces are marked by harsh winters and working continuously in the sun leads them to have darker skin and an apparently older physique.

Great unity, an incredible energetic spirit, and emotions like happiness and joy never disappear from their faces. Sensations that also drag themselves during the migration between the forests of the Hovsgol province, as they move along with the hundreds of reindeer in a new sacred wood, «inhabited» by the sacred spirits of their ancestors with which they come into contact through singing and dancing.

In this country, between mysticism and spirituality, there are still shamans. They use their healing powers only on the seventh and ninth full moon days and basically believe in three fundamental concepts. The first is that the world is alive: plants, animals, rocks and water have spirits and must be respected, thus giving protection and balance. The second point is personal responsibility.

Mongol shamans believe in the concept called «bujan» – which is very close to «karma» – that is, as the fruit of actions performed by every living being affects both reincarnation in a second life, and the joys and sorrows that characterize this second «opportunity». The third point is balance. It is of great importance as it maintains harmony within oneself, within the community and in the surrounding environment.

Shamans like Nergui, a man of advanced age who lives with his wife inside a small, narrow wooden house. Everything is enveloping and surreal.

Its role is to act as a glue between the songs of the forest ancestors, its people and their reindeer. Nergui, like other shamans, cannot exist except in the midst of a mighty nature that inspires him, but nature, and he is aware of it, is an inner dimension. The shaman projects what he has inside his soul. This is why the encounter with a shaman turns out to be an incredible healing and open-minded experience. He can recognize your problem without having to talk to him. The real difficulty lies in the approach and in breaking down all those conjectures and mental blocks acquired through a specific culture.

One of the first things that the shamans of Mongolia, totally covered by their traditional colorful clothes and folkloric masks, do to the person they have in front of them and who asks for protection, luck or abundance is to shake the negative energies off them. As soon as they enter a state of trance they begin to dance and sing with a tone that gradually grows together with the rolling on the leather drum.

Then they sprinkle it with smoke deriving from the juniper to recall the ancestors, who are attracted by the perfumes. Finally, they offer the spirits what our ego, the person in question, experiences the most egoistic «attachments» and that seems precious to us. Those mental and material certainties of which we do not do without in the context in which we live, like a pack of cigarettes or biscuits.

Only a few have remained to live in these conditions, in the taiga and throughout the year. Even the dialect is destined to disappear.However, for the common good, people have learned to respect the surrounding nature and animals and to pass on their beliefs, from generation to generation, invoking with songs and their deceased ancestors. And it is for all this that finding oneself in a similar scenario, despite the latest changes, can only be one of the most authentic and shocking experiences of life.

About Matteo Maimone

Matteo Maimone was born in Italy, on September 14, 1990 where he completed his studies. In 2009 he dedicated himself to photography. As a keen observer of daily life, he intends photography as a research, an introspection, through which he tells in a personal way cultural and social realities of his own country and more. That’s all thanks to photographer’s influences like Eugene Smith, James Nachtwey and finally Robert Frank. Matteo is able to create a versatile and original style embracing documentary photography.

At the moment he lives and works in Australia, running his project Nutshell Travel – a journey around the world chasing down stories – as a freelance photographer. Since 2017 he has been documenting a long term project about the daily life and social facts in many parts of Asia. He has been published in Dolce Vita Magazine, Erodoto108, The Trip Mag, QcodeMagazine, Wtness Journal, Positive Magazine and others. [Official Website]