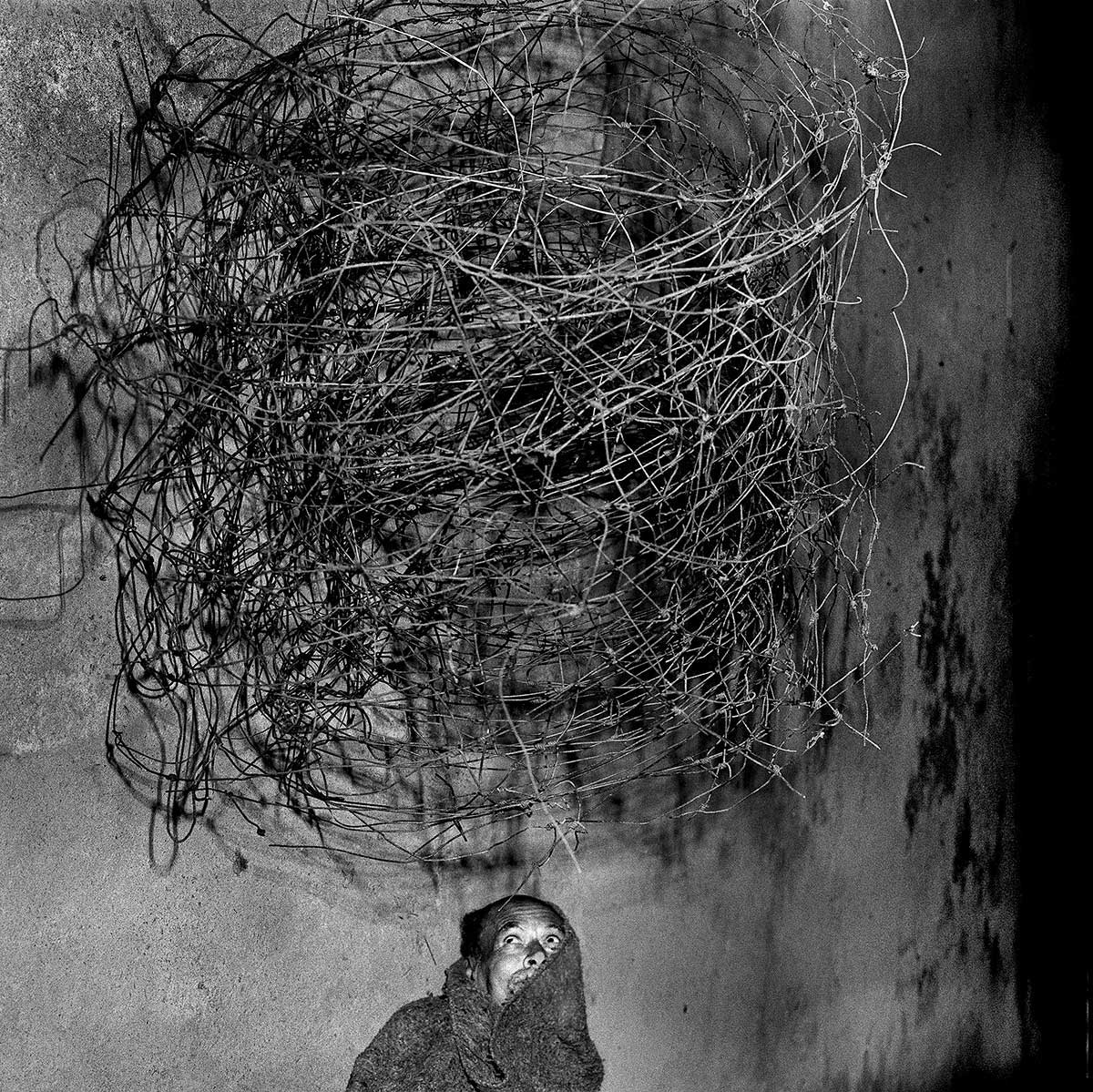

Roger Ballen was born in New York in 1950 but for over 30 years he has lived and worked in South Africa. His work as a geologist took him out into the countryside and led him to take up his camera and explore the hidden world of small South African towns.

At first he explored the empty streets in the glare of the midday sun but, once he had made the step of knocking on people’s doors, he discovered a world inside these houses which was to have a profound effect on his work. These interiors with their distinctive collections of objects and the occupants within these closed worlds took his unique vision on a path from social critique to the creation of metaphors for the inner mind. After 1994 he no longer looked to the countryside for his subject matter finding it closer to home in Johannesburg.

Roger Ballen is one of the most influential and important photographic artists of the 21st century, Roger Ballen’s photographs span over forty years. His strange and extreme works confront the viewer and challenge them to come with him on a journey into their own minds as he explores the deeper recesses of his own. [Official Website]

I see your photographs as conscious – subconscious game of composing objects of your interest. Persons, animals, things are just pieces on the canvas. It is kind of artistic creative trance where we are trying to enter in more profound parts of us, interrupted frequently by our ego.

Trying to understand the meaning or message of the resulting art, is just pathetic human intention to be clever, to explain everything around him. I am impressed with aesthetic consistence of your work. From the first series until today you are showing us “the beauty of the ugliness”. Would you like to say something about that?

Roger: It’s clear from the very beginning that my work has always been a psychological expression of my deeper needs, my deeper instincts and of my deeper feelings. It has been like that since the nineteen-sixties to the present, my work always had a psychological edge.

Photography is a means by which I can explore my deeper self, my subconscious. This has always been a purpose. I never considered myself a political or cultural photographer. I think that the issues that my photographs reveal ultimately have something to do with existential issues, and the shifts they have to create existential responses for other people. That’s my hope; even though I love what I’m doing, I’m trying to better understand my own psyche and hopefully assisting other people in doing so throughout my own process.

Looking at your work I have frequently a sensation of post-apocalyptic ambience, animals, objects and persons change their relationships. In your photographs, animals and persons live together, and bunch of wire or broken chairs become important elements in the images. We know that, unfortunately, many people in the world live in similar conditions, but do you think that in your work exist some (maybe subconscious) premonition about the future of the human race?

Roger: The thing is, when you look at my work, some people see this poverty that I’m photographing but this really misses the point. It really does miss the point.

What you see is chaos, what you see is disorder; the subconscious of mind expressing itself in is somewhat incoherent way. So, this ultimately affects people in a certain way because people spend their lives trying to create order, to prevent unknown things happening in their lives. They are trying to control nature; control events and they don’t want anything to do with chaos which ultimately rules life.

Chaos rules life. We can’t control everything and, in the end, we are going to die in some way or another, and we can’t control it. It’s written in the books.

It’s not possible to know how we are going to die, and we don’t know what’s going to happen the next day, nor anything about the future. So when you look at my works, you see a disorder and chaos, which is disturbing to people. They don’t want to deal with that issue of life. They want life to be organized, predictable, coherent; and they do everything possible to repress disorder and chaos.

And so, my pictures bring out that disturbing emotions. I wouldn’t necessarily say that the pictures mean or represent a view of what the future is.

I’m not certain whether I can actually predict the future, but they can provide a warning if we continue to do what we are doing; that it might lead to another breakdown in the world around us. There are so many variables that could affect the future, good ones, bad ones, inexpressible ones. It is difficult to me to actually say that I can predict the future in a real way.

In your early video interview, you speak about experiences in the painting and the importance of aesthetic in your work. Do you consider that exists in photography, and are these rules changing in time?

Roger: The question is good. I think that, in the end, there’s an alienation, a separation between the animals, the people and the places. So, you know, this is a reflection of the state of the world. This is the state of adversity between the natural world and the human world.

As for the rules, we can see that art has become a tool, not only for the media but for politics and other things as well. Art has been changing in the last decades, so the new generations are not following the traditional “rules”.

I think that the effects of media and the internet is seen in how a lot of well-known artists have become celebrities and very fashionable artists.

Every author has his own opinion about his artwork. We all have our favorites, the pieces of our work we consider better than others. Do you think that your favorites are also recognized by critics and audience as the best?

Certain images, for whatever reason, are more attracting to the public than others. And sometimes, you can understand why. I can understand why the public thinks of any picture as challenging or pleasing to look at. Why they think it is interesting to talk about. But generally speaking, people, viewers, they tend to cluster around certain pictures you have done over the years and not on others. And it doesn’t mean that those are my favorite photographs.

On many, many occasions, they are not my favorite photographs. What the publics likes isn’t necessarily what I like.

But there’s also the many occasions where the public indeed like what I like.

I don’t normally release pictures in books or magazines that I don’t like or that don’t have something fundamentally good in them.

I think it is a mistake to show people pictures that you don’t feel confident about.

During all your career you used to work with square format, in the last work you changed that. What’s your opinion on square format?

Roger: I have been working on square format since 1982, and the reason I like square format is very simple and clear. You know, I’m very formalistic in my work. I see my photographs as organic, like the human body or an animal body. Everything is there for a reason, everything is related.

Everything should link with everything and reinforce the meaning of my photographs. A square is a perfect form and everything within that form has an equal balance, but for example if you have a long rectangular 16 by 9, its sort of showing that the longer side is more important than the upper side, so it automatically prejudices the organic nature of the picture.

The form is very important. I don’t like pictures that don’t hold together, and many photographers don’t even think about the word “form”. Form is not an issue for most people in photography; it is very content orientated, you know, as long as there is something interesting for the photographer or the viewer, that’s all that matters.

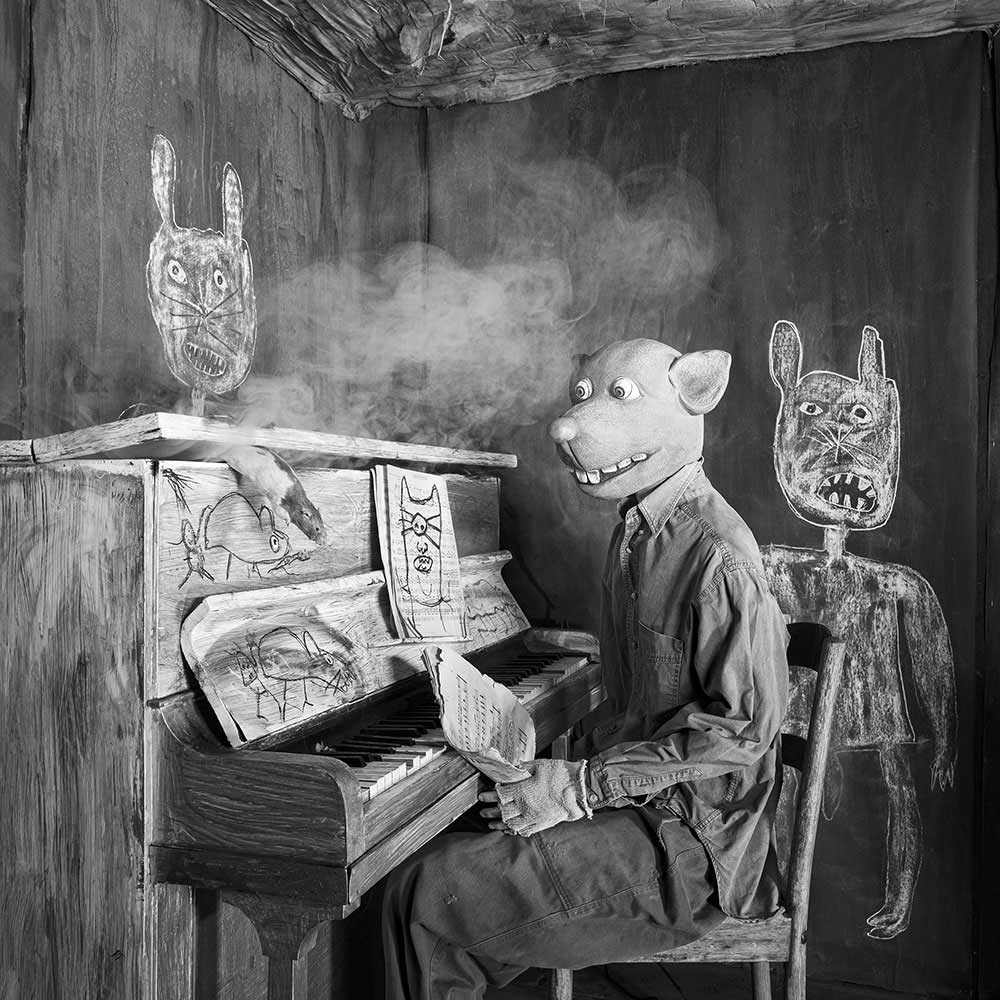

Can you tell us about your project of “Roger the rat”? We get the idea to represent the human being as a rat. Can you tell us why the rat and not another animal? The rat is the symbol of the plague. Do you show us humanity as a plague for this planet?

Roger: I think there are a few reasons I chose rats. The first one is my previous project from 2009 to 2014 called “The Asylum of the Birds”. I spent five years photographing birds at a particular house in Johannesburg where the birds live with the people; not living in cages but flying around the house.

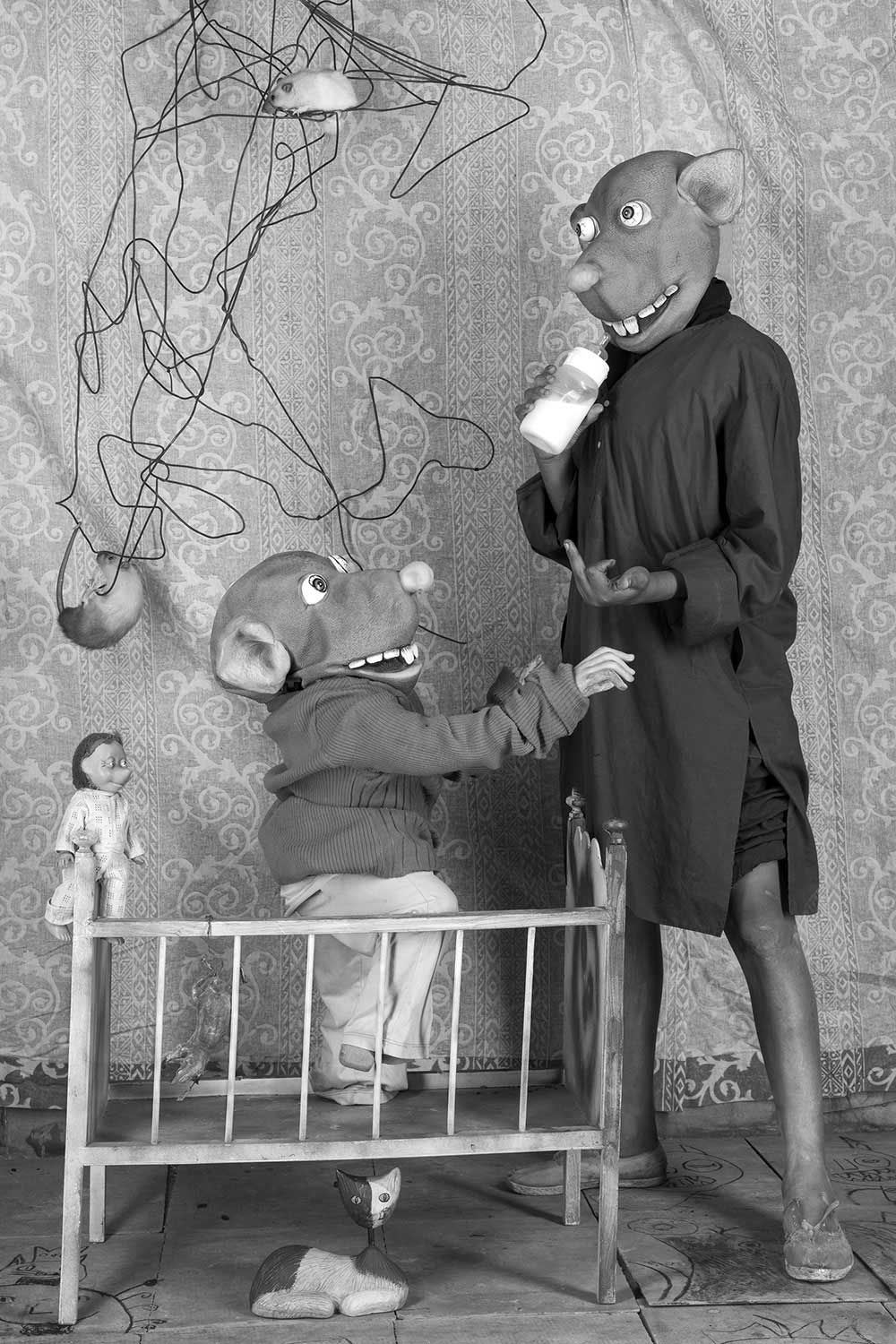

I found it interesting to work with rats because in western culture they represent dirt, chaos and disease. People hates rats. So, it was like trying to combine a compendium of work, one representing good and the other, the devil. I spent 4 years, from 2014 to 2018 doing the rat project. At the same time, in 2014, I began to work on “Roger the rat”. I worked on two rat projects. In Roger the Rat, it is a cartoon-like character.

Perhaps it could have been another animal, like a fox or maybe a wolf. Basically, Roger does things that are politically incorrect. He does things that are abnormal, things that people feel very uneasy about.

The rat character fits in with the concept of something that people don’t want to come into contact with. People don’t want to come into contact with people who do whatever they want to do [in the context of not having morals] just as they don’t want anything to do with rats.

Why the name Roger? Does it have something to do with you?

Roger: Roger created Roger the Rat, so he symbolizes an alter ego.

Does it have anything to do with a post-apocalyptic atmosphere? Maybe the rat is the only specie which could have survived the human destructive impetus?

Roger: The rat is a very intelligent animal, so yes. The rat is like my photography. It makes people anxious; it brings out emotions that makes them scared. There is some correlation between what the rat does to the subconscious mind and what my photography does to the subconscious mind.

Rats represent everything that people are subconsciously scared about, so they represent this disorder I’m talking about in my photography.

Where you see the strength of moving pictures and where the power of still images-photography?

Roger: Still photograph deals with the moment. It’s an instantaneous point in time. It’s a two-dimensional object in which the narrative has to be completed in a short frame of time. Everything is in a singular picture and asked to be interpreted within this singular frame, within a two-dimensional space.

Filming is very, very different. Film is very time-orientated, and the narrative is more extensive. The narrative is much more complete as film is made of thousands and thousands of photographs. 24 shots per second. It says something over a period of time rather than a point in time. You are able to read more than in photography. It has a beginning and a conclusion. It’s more of story.

Do you think that convenience of digital photography and enormous quantity of photographs we see every day make the audience start to look at photography as ¨easy reading¨ art, where the visual impact became more important than the deeper messages?

Roger: Most don’t understand about aesthetics. That’s the problem. There’s no understanding of history, context, aesthetics or art. They don’t get what the process is even about.

The scenography of your movie Roger the Rat is really amazing. Could you tell us something more about where and how was made?

Roger: The entire Roger the Rat series was made in South Africa, in a period of [more or less] five years. I made most of the sets for those photographs.

The movie was made in a prototype house made in a warehouse. It’s a wooden house with four or five rooms which I made some years ago. I’ve left the house the way it was built, and I use this place to make films and some of my photographs. Sometimes I might change the wallpaper of the house, or make a painting in the wall, take pictures and then put something else again [so as to change the photographs].

Are you thinking of doing something else besides Roger the Rat in this house? [In the sense of another big project instead of photographs]

Roger: This house has been important to my career, so I would like to keep taking pictures and making films in there. I think the next movie that I’d like to make up, speaking to a few people, is a biography or a documentary about my life and my photography.

I have this goal, I’m trying to find the right people and organization to make this movie, so, you know, I guess that to make a movie like that, it would be a place like this.

Mitar Terzic

Serbian born, Mitar Terzic lives in Spain, in Alicante. He practice photography for twenty years . Mitar presents a phantasmagoric universe with the masks that he draws and makes by himself. Black & white photos, in square format, are both intriguing and poetic and take us into a world where everyone can imagine his own versión of the story.