The world has ironically forgiven to see the common habits and values in our global world, everything that makes us have the same feelings and emotions.

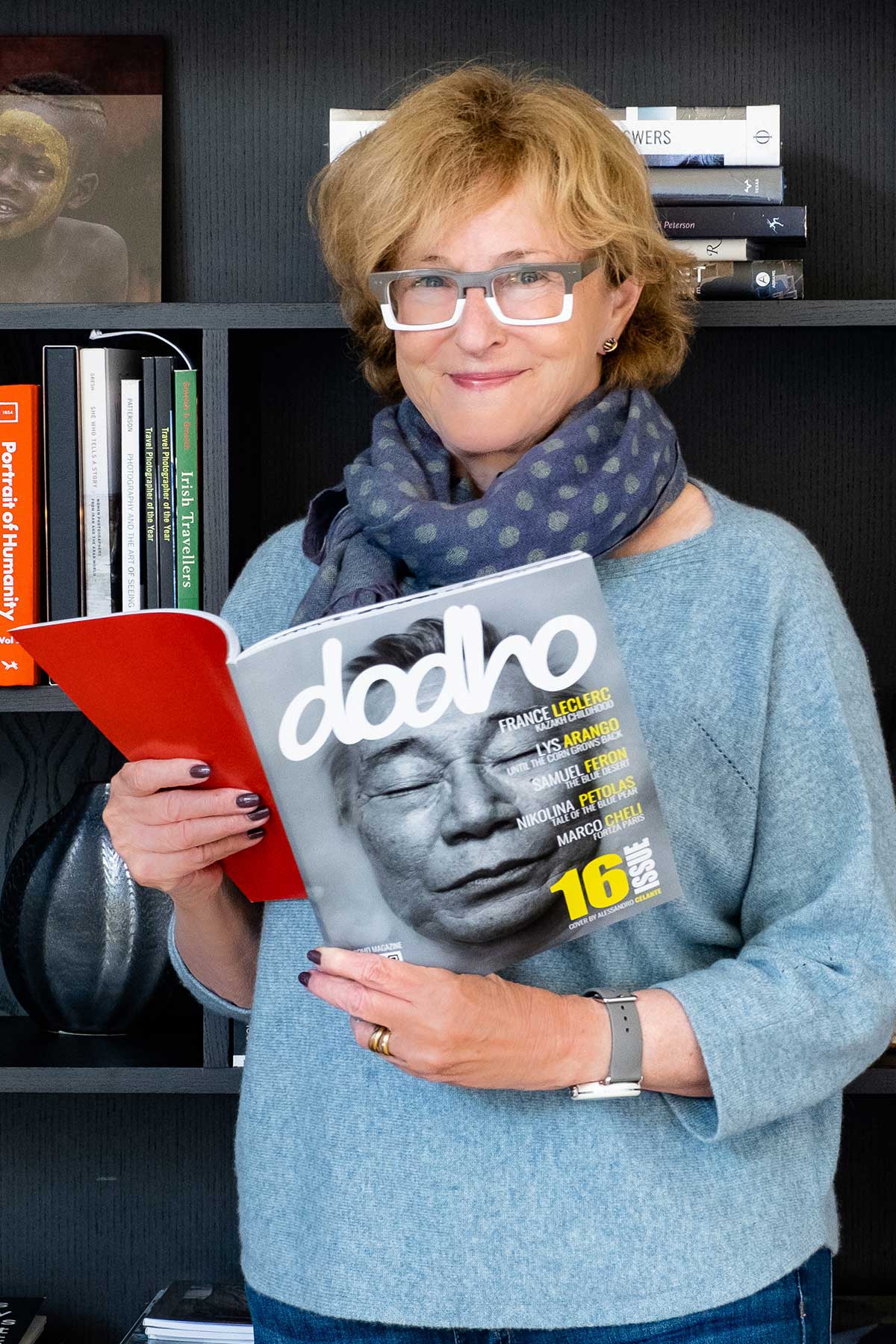

Canadian Travel photographer France Leclerc tries to find this commonness with joy showing sweet observation through fresh eyes to portray ethnic group communities the world seems to ignore. I had the chance to have this conversation with her and learn about her looking in from the heart. This full anecdote interview is a delight to read. [Official Website][Printed Edition][Digital Edition]

Focusing on the children’s lives in various ethnic group communities to find out the common core values we share, that’s a wonderful human message calling for empathy in these weird times. I wonder if you can tell us some stories or anecdotes related to playing and games you have observed during your process of work. And also, on a more personal level, do you find any connection between your photo narratives and your own childhood?

Playing is part of children’s lives all over the world, even the ones facing hardship or heavily involved in helping the parents. Thankfully, children are remarkably inventive in finding ways to play. Some of the games are pretty similar to ours too, but what differs is, of course, the quality of the equipment. As they have very little, they have to be quite creative.

I saw a group of children in Bangladesh playing badminton, but they only had one racket, so the game became one of hitting the shuttlecock with «the» racket as far as possible, and the rest of the children would run to catch it. The one who caught it would then get the racket next and would swing away.

Soccer is, of course, popular everywhere, even in isolated tribal areas of Africa; I have seen homemade soccer balls made from almost anything imaginable. As for my youth, I grew up in Quebec, Canada, and none of the countries, I have visited I have seen the need to recreate an ice rink; maybe if I get to Mongolia in the winter.

With respect to animals, how would you describe the relation to animals in these exotic locations compared to the perception of animals of the people living in cities? And what challenges have you found shooting them?

In many remote areas I have traveled to, animals (horses, cattle, goats, camels) are the primary family possession. Their animals are what allows them to feed themselves and earn a little money. Thus, animals are treated with great respect (and of course, in some countries like India, cows are sacred animals, but that is another story). Children start relating to animals and taking care there of them at a very young age. The bond between children and animals is profound. For example, boys of the Wodaabe tribe, a nomadic tribe in the Sahel desert, start taking care of the precious Zebu cattle at age seven and show enormous pride when they reach this level. I photograph animals with a relationship with humans, so it is not as challenging as photographing wildlife. Still, I try to keep my distance from the Zebu cattle and their enormous horns.

Born in Quebec, living in Chicago and photographing far and difficult to get communities. How do you find out these places? Where do you get the info about them, that means which are your sources? How do you get to finally choose a place? What moves you?

I have always been a traveler, even before being a photographer. I have always been curious about other cultures. In fact, in my academic life, I taught a course on global marketing, and on trips, I was collecting ads or packaging from all over the world. When I first started to photograph, I often went with groups because that made it easier to reach remote destinations. That was a great way to get started, and it worked well for me for a while. Over time, however, I began to get frustrated because I had little control over the time I spent in a particular place; just as I would get interested in a story, it would be time to leave. So now I mostly organize trips on my own, something I would not have been able to do initially. Through the group trips, I have managed to meet enough people over the years who can give me recommendations for local guides or “fixers” pretty much all over the world. When I have an idea of a place to go or a story I would like to document (and that can come from anywhere, a conversation with a friend, an article in the daily newspaper, a book I am reading), then I try to research the location/topic as much as possible before the trip, also looking for what has been done on the subject.

Are there already great photo essays out there? Can I do something different than what was done? Can I have my own angle on the topic? Usually, what moves me is, quite broadly, the human story. What can show from my subjects’ lives that will make the rest of the world want to relate to them and feel some kinship?

It is often children, but also women’s lives, economic challenges, special rituals.

You seem to enjoy the process of learning through photography. That says a lot about you as an artist and as a person. It’s definitely an open and global vision. Congrats on that. What are you still looking forward to learning through photography? And which are your next steps?

Well, needless to say, we have all had to change our lives quite a bit over the past year. Remote travel has been impossible. One upside of this is that it has forced me to look a little more deeply into my surroundings.

Like the kids that have to create their own soccer ball, I have been nudged to pay more attention to the people in my community. Looking forward, understanding through photography how newcomers with different backgrounds adapt to their new lives in our country is something that I would like to explore.

When it is finally safe to go back to traveling, I hope to pursue my growing interest in people who live nomadic lives.

You have captured people from different cultures and have got quite close to them, to a level of documenting intimate moments: sleeping, praying, house cleaning, dancing, body freedom activism, cooking, or playing. These human rituals and behaviors are not easy to photograph, how do you get their trust? And how do you manage at the same time to take interesting images on a compositional level?

Developing trust is a long process, but this is where having a good local contact is essential. How you relate to people is also part of the equation. When possible (it is often challenging to overcome language barriers), I try to explain why I want to photograph them and what I want to tell people about their lives. But since what I do is primarily candid photography, the challenge is to have the people forget about me being there as much as possible. In the beginning, everyone is self-conscious, and subjects try to give you what they think you want, which is often wrong. I sometimes do portraits at this point so that they feel like we are progressing.

But what I am interested in is them living their lives as if I was not there. I wait until they are tired of paying attention to me, so they go on with their activities; this is the time for me to photograph as unobtrusively as I can. And if you observe long enough, the composition comes into place; you notice elements you want to include in your frame. I also enjoy street photography, which is a somewhat different approach but also gets you “authentic” moments.

You have developed your own style in social documentary photography. What piece of advice would you give photographers who are still finding their own voices?

This is a hard question. The only advice I would give is to do what you like and maybe get some editing guidance from someone you trust. I think it takes a long time to find your voice; it is an evolution.

Your Instagram is a colorful feast with amazing and powerful portraits. In this global world connected by social networks, how do you relate to them? Describe to me how you personally use them.

The only social medium where I am truly active is Instagram.

I like the idea of sharing an image, sometimes a current one, sometimes an old one, and enjoy the fact that people from all over the world can see it and react. I try to post every two days or so, but I am not strategic about it, probably not enough. I love when someone can relate to the posted image at a personal level, either by being from the country or the town where the image was photographed or even sometimes recognizing the person on the photo. It makes me feel that we are indeed all connected.

Seigar

Seigar is a passionate travel, street, social-documentary, conceptual, and pop visual artist based in Tenerife, Spain. He feels obsessed with the pop culture that he shows in his works. He has explored photography, video art, writing, and collage. He writes for some media. His main inspirations are traveling and people. His aim as an artist is to tell tales with his camera, creating a continuous storyline from his trips and encounters. He is a philologist and works as a secondary school teacher. He is a self-taught visual artist, though he has done a two years course in advanced photography and one in cinema and television. His most ambitious projects so far are his Plastic People and Tales of a City. He has participated in several international exhibitions, festivals, and cultural events. His works have been featured in numerous publications worldwide. His last interests are documenting identity and spreading the message of the Latin phrase: Carpe Diem. Recently, he received the Rafael Ramos García International Photography Award. He shares art and culture in his blog: Pop Sonality.