In an area of Colombia called Carrezal a community of gold miners continues its struggle for survival

In Columbia the cocaine business has become less important than in past years. It is the land now, with its enourmous riches hidden in the subsoil, and the consequent lucrative management of extraction, inflaming economic interest and violence. The gold fever has returned, supported by the exchange rate of 1111 Dollars per Ounce, almost 32 Euros per gram.

To have access and control of the agricultural land and forests, the local population, mainly campesinos and miners, are being expelled with force. An escalation in massacres and rape, that foments forced eviction, the desplazamento, is becoming evermore evident in the suburbs of the big cities such as Bogotà and Medellin. Every day thousands of displaced people pour into these shanty towns controlled by criminal gangs. Columbia is the second country in the World, behind Sudan, for the number of displaced people due to acts of war.

Carrezal, in the Antioquia region, is a small village made up of shacks perched on the mountains. It lies close to a jungle that has been partially destroyed by savage deforestation, and is one of the country’s “hot spots”. Here, for over thirty years FARC, ELN, paramilitary groups, and the government army have been fighting. Mostly for political reasons, but increasingly for the control of the territory, rich in gold.

The mine was dug twenty seven years ago, but was abandoned after only three years due to the constant violence and oppression directed towards the miners. Gathered together in cooperatives, the miners re-opened it in 2008 requesting the Government to legalize their activity on their land, owned for generations.

They have never received a reply to this request, as the Columbian administration prefers to sell the licences to foreign multinational corporations, primarily from Canada.

Like Carrezal, there are many other small mining villages, considered illegal with the sole purpose to discredit the legitimate owners and exploit their properties, opening the door to considerable foreign investment through substantial bribes. Despite threats and bloody reprisals inflicted by multinational-paid paramilitaries and supported by some members of the Columbian Conservative Party, the miners have continued to dig and extract gold, not succumbing to intimidation. El Dorado may only be a legend, but the bowels of these lands still have immense quantities of gold, visible with the naked eye.

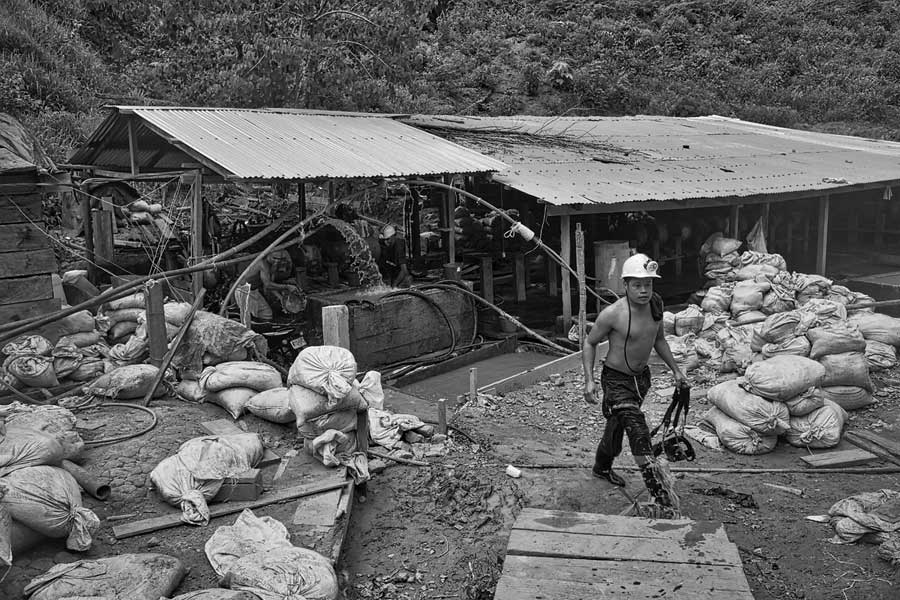

Forget about modern mines with trucks, excavators, lifts, emergency exits and emergency rescue teams: here there is no running electricity, but old diesel power generators, constructions in wood and rope, and pipes of worn-out rubber tubes. I was expecting something similar, but rather than a mine, this place feels like a real mouse-trap.

Working with makeshift means, the waste materials produced are also managed in an approximate way: In addition to the indiscriminate felling of trees used for indispensable boards to prop up tunnels, there is also chemical waste, such as mercury, used in liquids, essential for seperating the precious gold from its sediments. None of the miners have adequate protection clothing and therefore come into contact with these toxics on their skin and in their lungs. Furthermore these liquids are then dumped into the water system.

Antioquia is one of the most polluted regions in the country: it is estimated that more than 30 thousand miners every year release 67 Tons of mercury. Dozens of men work in Carrezal’s mine: every day they descend over 500 meters in depth, walking down unstable wooden steps, slimy from the mud and water that continuously spill from the walls. The entrance of the tunnel is vertical and the sunlight disappear almost immediately.

A leap into the dark where one feels enclosed by the obscurity; a complete darkness, pitch-black, flickered by the only source of light from torches attached to the miners’ helmets. A real nightmare made evermore overwhelming and suffocating by the increasing heat. The air becomes thin, and has to be pumped into the mine by a big rubber pipe. The risks increase with every step taken to descend. The entire mountain is rich in water, which constantly has to be extracted to avoid sudden floods in the tunnels. There is only one entrance, which also serves as the exit, hindering the miners’ ability to escape. In fact, some months ago eight people drowned because of a problem with the mine’s draining pump.

The nightmare occurs on occasions where the old engine at surface level breaks down, and the water in the tunnels begins to rise very quickly. All the miners working at depth are hurriedly recalled up to the surface, as the tunnels are the first to flood.

Gathered at a depth of 260m in large sorting room, the men remain undecided whether to make a rush towards the exit or to hope that the engine restarts.

When the water level arrives at waist-height, some begin to pray. Others try to determine if the problem is caused by a blockage in the pipe attempting to clean it with their bare hands.

This time their prayers are answered as the old engine restarts. Joking about what has just happened, but visibly relieved, the miners go back to work, each to his own task. They dig using pickaxes, filling sacks of 75kg and, carrying them on their shoulders up to the surface. Seven journeys for each person. Seven kilometers vertically with a total weight of 525kg each day.

A work for slaves where every step taken, every drop of sweat poured, every minute of fatigue means feeding their families. The intense light, the pats on my back by the other miners and the loud clamor of machinery welcome me back to the surface. The noise is caused by the fragmentation process of the rocks, crushing them into powder. The powder is then mixed with mercury by hand, obtaining a dense, silver-coloured material.

To separate the mercury from the gold, a melting pot is used with a temperature of over 1000°C. Once cooled, the gold is weighed and registered. The waste of this process, reduced to a muddy paste, is then “washed” in metal containers with cyanide and other chemicals, and later condensed using mercury. In this phase it is impossible to foresee the final quantity and quality of the gold; indeed sometimes from 500kg only 300g are retrieved.

A third method of extraction, the less profitable, involves the wasted rock blasted with explosive charges, during the construction of new tunnels. The stones are thereafter split using pickaxes, washed and checked one by one. “Our gold is sold here directly to Columbian buyers”, explains Johan. He is 27 years old, with a strong desire to leave this life behind him as soon as possible. “We work from 8 am to 3 pm and the monthly pay is the division of 40% of the extracted gold. The remaining 60% is put into a common fund for management expenses, although a part of this finishes in the pockets of corrupt police officers. We also receive four sacks each to sift ourselves”.

For extra work, such as repairing machines and welding, the men can earn a million pesos, around 600 euros. A good payment considering that in Columbia the minimum wage in the public sector is 680 thousand pesos. The work however in the mine is extremely dangerous, and therefore less people are prepared to do it, preferring to make ends meet with what they can find in the external stages. The life expectancy of a miner is 45 years “If paramilitary soldiers don’t kill you before”, says Johan ironically. “We would like to modernize every phase of the mine to increase safety and productivity, but at this time we don’t believe in investing money into a structure deemed illegal by the Government, with the risk of seeing it confiscated or burned down by paramilitaries”.

In Carrezal everything seems temporary; work, the houses, and peoples’ lives. The mine influences the whole village, with the threat of having to pack up and leave suddenly, overshadowing the people, suffocating any prospect in life. Nothing else is produced here. Local farming has been abandoned and everything is transported at an expensive cost from the nearest city, Segovia, seven hours away by a civa, an old American bus, used in the 1950’s. Food and alcohol are bought in the small shop, that also serves as a bar and a meeting place.

Johan hosts me for lunch; his house is small, 3m for 2m, with a bed, a small gas stove, a television, and a couple of rifles hung on the wooden wall.

“In case anyone tries to steal my gold”, he jokes, sensing my uncertainty of the weapons. He talks about his dreams, his hopes, his future together with a Spanish volunteer he met some years ago here in Carrezal. I listen to him but can’t avoid noticing his eyes that are smiling, but are also full of sadness. Perhaps he knows that his life, at least for now, is bound to the mine.

Technical notes: Canon Eos 5D Mark III with Canon EF 28 mm

Erberto Zani (1978) is a photographer and journalist freelance based in Italy. His works of social documentary photographer include reportage from many difficult areas of the world: illegal gold mining in Colombia, war for minerals in North Kivu (D.R.Congo), earthquake’s effect in Haiti, landmines in Cambodia, water crises in Burkina Faso, Somali refugee in Nepal, daily life inside the favelas of Medellin, miners of coal in Jharkhand and Hindu festival of Maha Kumbh Mela in India, Syrian refugee in Lebanon.

Erberto Zani, available for assignment, cooperate with several magazine and international no profit organizations especially for editorial projects. He published several books: “Maha Kumbh Mela” (2014), “Tsiry” (2014), “Babanagar-Colombia” (2013), “Sahel” (2012), “Hope” (2011), “Haiti, fragments” (2010), “Drops of life” (2010). [Official Website]