From the cobbled streets of Milano to rustic pathways that transcend borders, photography has been a tool that has enabled artists like Francesco Merlini to capture moments, emotions, and narratives that often go beyond what words can express. Merlini is not just any photographer.

His works embody a blend of documentary roots coupled with a profound interest in metaphors and symbolism, elements intricately woven into his captured images. His acclaim has been swift and ever-growing. In 2016, he was handpicked by the prestigious British Journal of Photography to be featured in their “Ones to Watch” edition. He’s been nominated and recognized by esteemed institutions such as the Prix HSBC pour la Photographie and the Leica Oskar Barnack Award. Furthermore, in 2023, his prowess earned him a notable mention in the Sony World Photography Awards.

Now, he introduces us to “Better in the Dark than His Rider,” a work published with Depart Pour l’Image that swiftly garnered recognition, even being selected by the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson as their book of the month. Such accolades not only validate the calibre of his work but also reflect the deep resonance his images hold for those who view them.

The Dream Passenger by Luca Reffo

Endless tossing with eyes closed, exposed to any random glance.1 Born out of a reflection on the nature of images and their nocturnal vocation, Better in the Dark Than His Rider is both a fable and a survival guide.

Where the fairytale begins near the final pages, with the appearance of animal presences, a pair of donkeys, and two boys caught in the act of fishing in a river in Togo, the book also embodies a manual of salvation for the imagery and its animate matter.

The collected work by Francesco Merlini spans different years, possibly quite distant from one other; shot in all four continents, his pictures reveal the unique perspective of someone who, like a sleepwalker guided by ghosts, seeks for something nameless. The first working title of the book was the evocative Finnish word “haaveilla”, for it so naturally embraces a gaze as foreign to this world, erratic and remote and amnesiac, newly born and divergent from opportunities, as the look of wanderers. The Finno-Ugric term “haaveilla” includes the noun haave which means “dream” or “longing”, and the suffix illa which corresponds to the length of an action. The English translation is “to daydream” or “to stargaze”, and yet there is no hint of daytime here, only the promise of an act set in a time beyond the night. Also, the word aave (i.e. “ghost”) indirectly connects haaveilla with a state of mind that seems plunged into shade, inhabited by spirits of desire.

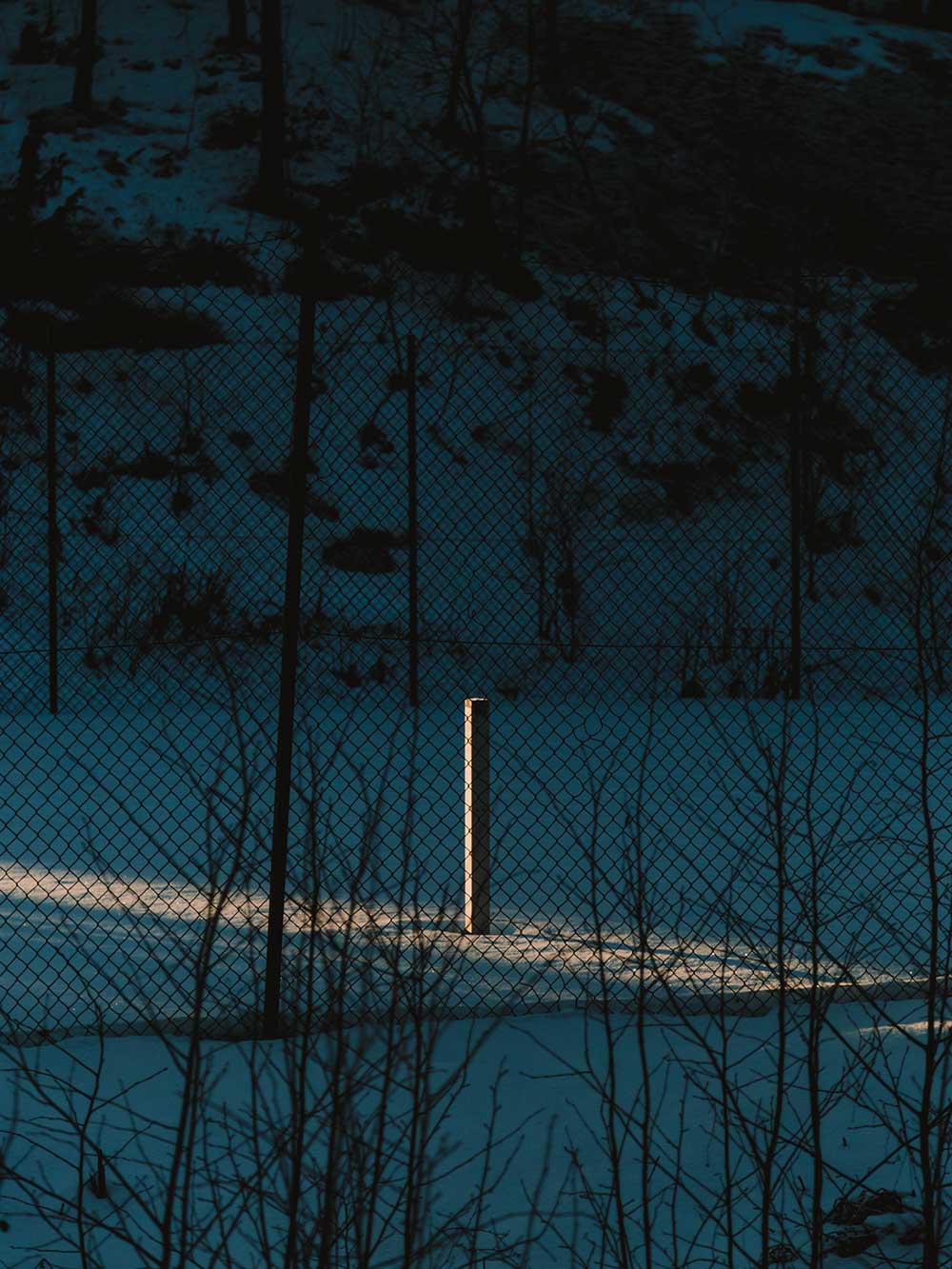

The present title is instead drawn, almost literally, from a 19th century manual of optics.2 The original sentence – “[…] much better in the dark than his rider” – refers to a horse’s night vision compared to a human’s. Such inversion of the primacy of man over other animals suggests how images fatally exceed their own meanings. The dual passage from rider to night passenger, and from human to animal, leads in fact to dreams, metamorphosis and myth. In order to come to senses, the night passenger needs to abjure the light of reason: the more their mind is allowed to wander the clearer the path to tangible vision will be. Their very conquest is to be possessed, their blind wandering going hand in hand with faith in poetic knowledge. The selected sequence of pictures unravels around the transitional stage between wakefulness and sleep, engaging with hypnagogia as a sensory yet dreamlike mode of semiconscious representation. Images make up mind’s psychic contents. Dreaming is a perpetual state we do experience both asleep and awake. By flexing the boundaries between conscious and unconscious, dreams float in in-between, porous spaces that blur any idea of beginning and end, rule and exception. The hypnagogic state of consciousness enacts a kaleidoscope of phantasmagorias – disrupted visual coalescences, geometries, intuitions, day residues, instant visions, partially unintended emotional associations –, therefore conjuring mixed combinations, contexts and representations: in other words, oneiric theatre.

The nineteenth-century illustration featured at page 14 shows a dream flowing from the obscure window of a lonely manor, within a constellation of symbols: ancient ruins paired with modern echoes, a steam train and a highly inventive bestiary as bizarre as the topic demands. With the book from which it was taken – Les Rêves et les moyens de les diriger (1867)3 –, not only has Léon d’Hervey de Saint-Denys recorded his dreams on a daily basis since the age of 13, but he also was the first to ever provide a theoretical framework for the oneiric dimension, along with a system of its analysis and control. If in dreams self-consciousness is suspended and images look real to the extent that we are sleeping, when dozing we can consciously guide them because partially aware that we are dreaming. Stated otherwise, in lucid dreams we know we are faced with the contents of our imagination, whose edges appear hallucinatory. Such acknowledgement, combined with the chance to exercise control, allows for a privileged perspective where the vision can involve creative action and mind transformation as already practiced for centuries in the Tibetan Buddhist and Sufi meditative traditions. Defined by the absence of perceptible data, context-less sensory connections and reduced synaptic synchronization, dreams become then predominantly visionary. They imply the temporary stillness of the observer who, rather than dreaming, witnesses the images by which they are visited and absorbed as if they were some paying spectator. Both the motor paralysis and the fleeting suppression of the senses show the oneiric activity during dozing and dreaming as the result of an impairment. Let us examine a couple of possible suggestions. The protagonist of Jack London’s The Star Rover is trapped twice in his death sentence and straightjacket, except that these merciless constraints let his individual psyche overcome its limits and experience out-of-body travel. In the novel by Cornell Woolrich Rear Window, Jeff (portrayed by James Stewart in Alfred Hitchcock’s namesake movie adaptation) is a chair-bound writer/observer nursing a broken leg, whose gaze is framed by his rear window and a pair of binoculars. Likewise, the act of shooting forces the photographer to instant immobilization and monocular vision, so that they look at the outside through one eye only.

Our visual gaze overlooking all things imaginary is suspended until it starts staring an image, which stares right back, looking straight at us and holding us hostage. Each image explicitly stems from the partial nature of its originating media. The resulting representation is then a grounding and penetrating force, the impetus for images to embrace their own finality in order to emerge. A picture, a song, a Fata Morgana or a dream – they are all distinct and separate entities built on the essential substruction which is innate to their form, whether mental or non-mental. Form itself is a gap, a passage, a narrow gorge where images flow endlessly, generating connections that are bound to inspire infinite visual spirals. A synthesis of emotional experiences, images hold nothing but affective contents. Thanks to imagination, the dream matter turns into the mind’s real object again. Consciousness as a mental state becomes a space vulnerable to offensives by the body’s internal environment – a reminiscence of ancient anatomy that once controlled the branchial respiration of our fish ancestors or, even further back in time, the transition from inorganic to organic life. Self-referentiality and immunity to exploitation for personal gains make dreams shift constantly between opposing tensions. The shadow is looming. While oneiric autonomy becomes apparent by escaping memory, its uniqueness demands to be heard before even being verbalized: dream images in quest for their dreamer love to be pronounced silently and to be chased without getting caught. Like animated maps, they elude reason and weave secret relationships between past and future: theirs is an anticipatory power; a prognosis that, by playing hide and seek, goes straight to the heart of things. In this regard, the arcane illustration on the back cover and on page 4 is the prelude giving the narrative pace to the fundamentals in Merlini’s work. The armored figure leaning over fire is taken from the frontispiece of an 1830’s text by Giovanni Aldini.4 With this small pamphlet, the author introduced a protective suit for firemen lined with cloth soaked in alum for the body and asbestos cloth for the face and hands. The fireman plunging his body into the flame suggests a connection between day and night, for the disguised figure operates in the dark. The masked fireman in our dream safeguards the survival of shadows and symbolizes the metamorphic knowledge driven by imagination: a portrait of subversion as iridescent as the animal coat during moulting. In this constantly changing landscape, a vital and wild dynamism proliferates, eclipsing in a chromatic spectrum between red and blue. Feelings as foundation to consciousness reach down deep for the promise of their own visual translation. In fact, we shall never forget that image doesn’t exist until it exists and neither is conceivable before its occurrence.

Imagination is an attempt at immortality that, by separating exceptions from the indistinct flow of stimuli, ensures the image’s redemption from oblivion. With eyes closed, ghosts arise and the wandering begins. Just like when the early bird comes across the last of the night owls, so we meet dreams and their immanent echo of the past while dozing. Similarly, in Better in the Dark Than His Rider the dreamlike state walks the shapeless path to the oneiric, until one last detour throws us into the arms of a story, hazy and unknown, as we are caught in the relentless stream of dreams. [Text by Luca Reffo]

1 – Franz Kafka, The Diaries of Franz Kafka: 1914–1923, Tr. by Martin Greenberg, with the co[1]operation of Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, New York 1949, see July 6th, 1916, Vol. 2, p. 158

2 – John Walker, The Philosophy of the Eye: Being a Familiar Exposition of its Mechanism, and of the Phenomena of Vision, with a View to the Evidence of Design, C. Knight, London 1837, p. 155. Illustration featured on page 69 of the present edition

3 – Léon Hervey de Saint-Denys, Les Rêves et les moyens de les diriger: observations pratiques, Amyot, Paris 1867, frontispiece

4 – Giovanni Aldini, A Short Account of Experiments Made in Italy and Recently Repeated in Geneva and Paris, for Preserving Human Life and Objects of Value from Destruction by Fire, To be had of P. Rolandi [et al.], London 1930, frontispiece