NATHAN WIRTH, FINALIST AND PUBLISHED IN OUR BLACK & WHITE 2019

NATHAN WIRTH, FINALIST AND PUBLISHED IN OUR BLACK & WHITE 2019

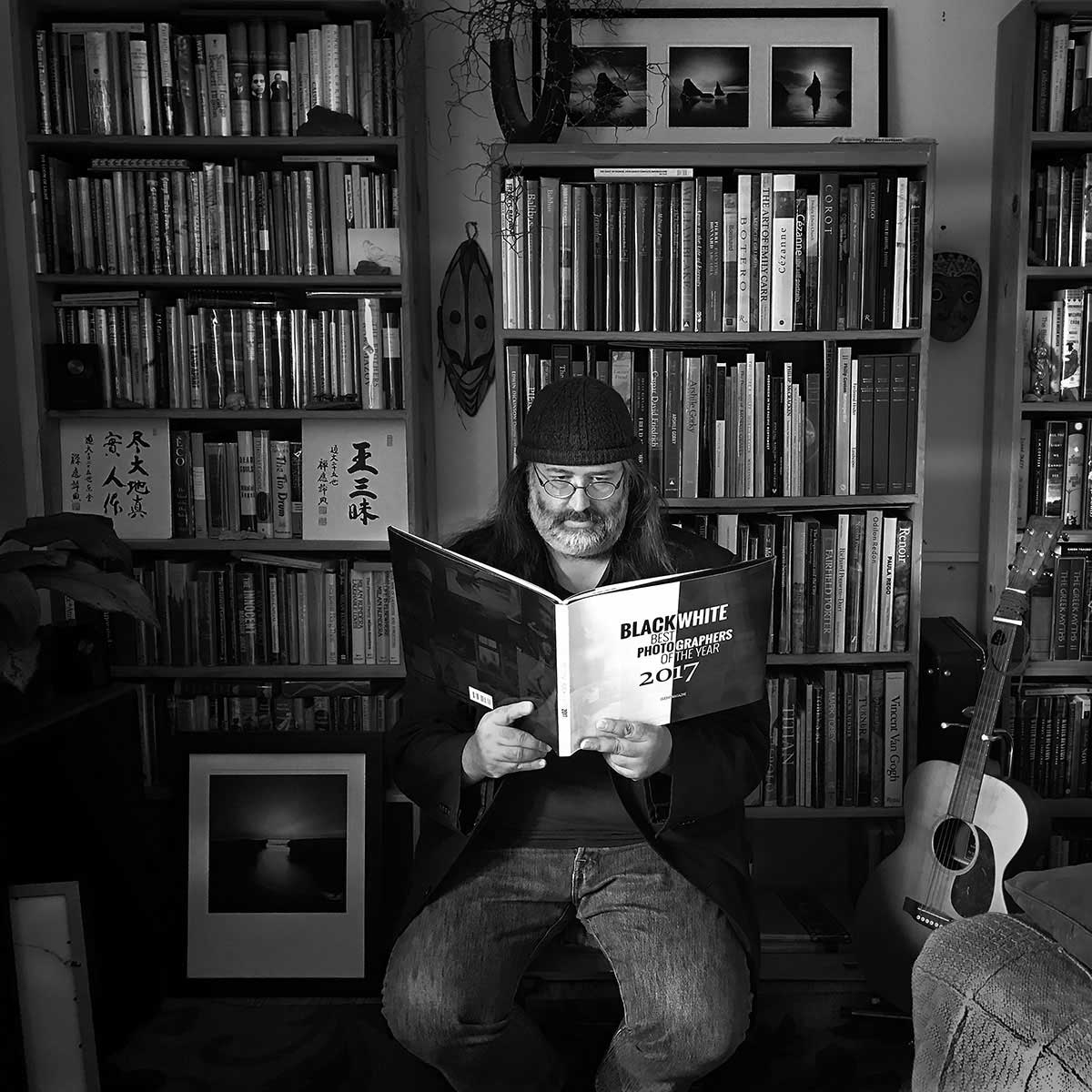

For over twelve years, Nathan Wirth, a native of San Fran- cisco who for the past ten years has been living with his wife and daughter in Marin County, has been attempting to photograph silence.

While there are most certainly a number of photographers, filmmakers, and painters that have had a significant influence on his pursuit of light and silence, poets and nature writers have played the most significant role in inspiring the 53-year-old photographer who earned both a BA and an MA in English Literature from San Francisco State University. In particular, poets such as George Oppen, Gary Snyder, Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, Lorine Niedecker and George Mackay Brown— and nature writers such as Emerson, Thoreau, Annie Dillard, and Robin Wall Kimerre— have significantly shaped his experiences photographing the shorelines, mountains, forests, and lone trees of California, Oregon and Was- hington.

For the past five years, Mr. Wirth has been studying and integrating into his work Japanese traditions of Zen, rock gardens, ma, Ikebana, haiku, and calligraphy as well as the transience, impermanence, and imperfections of wabi-sabi. His studies of Zen calligraphy and Zen writings have led him to the practice of trying to achieve a mind of no-mind (mu-shin no shin), a mind not preoccupied with emotions and thought, one that can, as freely as possible, simply create. Nathan makes his living teaching English at City College of San Francisco.

When I first analysed this body of work my initial thoughts were that of the photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto and his analysis of stillness when photographing seascapes. I think that the success of your body of work lies in this ability to not think too hard about the subject matter itself, rather relish in the beauty of its simplicity. Have you always been attracted to the framing of your subjects in this fashion, exploring this notion of calm and stillness in nature?

First of all, I have very fond memories of the first time I saw Sugimoto’s work at the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco. I was exceptionally moved by his seascapes with no horizons (and his images of the dioramas from the New York Museum of Natural History). What first impressed me was how much impact his very simple seascapes have— especially considering they were about as minimal as one can get. That said— I think the real connection with a photograph comes primarily from the viewer, and my experience of Sugimoto’s seascapes stemmed from my thoughts about art, beauty, nature, etc., and not as much from his intentions. In other words, I believe a photographer expresses whatever he or she expresses, but that expression belongs to that photographer only. Once the image is seen by another viewer, that viewer brings to his or her experience of the photo everything he or she knows, feels, wants, etc..

But, yes, I have strived to remove myself from the process of image making as much as possible. Many photographers talk about planning and having strategies and honing skills so that they can achieve mastery and be prepared to properly photograph the moment. Others talk about having a vision and shaping the image around their vision—or shaping their vision around the image. I, personally, have no interest in any of those approaches. I simply want to try to photograph silence. I really do not know if I succeed at doing so, nor do I expect anyone else to realize that this is what I try to do. Also—in saying that I try to photograph silence— I do not mean that I consciously do so or plan to do so or arrange things in order to do so. I just simply try to do so.

So, with all of that said, I do not think, in my photographs, I relish in the beauty or simplicity of the subject matter, nor do I explore the calm or stillness of a subject. I do not even explore silence. I simply try to photograph it. I do, however, relish in the beauty and simplicity (and complexity) of nature itself. And nature with its many moments of stillness often calms me. Visiting and experiencing nature is often very meditative for me, very contemplative. The making of an image is often very calming and contemplative for me. It has, over the years, evolved into a meditative practice.

Nevertheless, I would not be surprised to hear that there are those who see my images and think about the beauty of a tree or a rock or water slithering towards the sea after a winter rainstorm. I would also not be surprised to hear that someone found the image calming because of its stillness, but I would guess that is because that viewer tends to find nature itself calming and still and beautiful. I sometimes wonder if the only reason why someone might say to me, “Yes I see silence in your images,” is because I often claim that I try to photograph silence. In other words, I have influenced how someone might see one of my images because I stated my thoughts about silence. However, I would argue that those who see the silence, still see their own perception of silence which is likely very different than my conception of it.

When situating yourself in a landscape and preparing for a shoot, do you ever spend time either before or after reading the many poets and writers that have influenced your work?

Reading poetry is part of my life. I try to read at least a few new poems every day. Both my BA and MA are in English Literature—and a significant part of my studies were focused on poetry—and those studies have led to me becoming a lifetime reader.

Poetry has become a part of my image making only in the fact that reading poetry is a part of my life. I should add that I wanted to be a poet— and I write some poetry— but I am, quite honestly not very good at it. And that fact is part of the reason why I enjoy image making— which offers me a way to express something creatively that can be, at times, poetry-like but always not poetry.

I also never prepare for a shoot. I just go out and do it when I do it (which often ends up being when I have the spare time or, best, when I am traveling). I used to take time to prepare and plan, but I stopped— choosing instead to let my photography unravel when it unravels.

I was recently asked for one piece of photography advice– and I responded, “Read poetry.” The person who asked the question walked away with a perplexed look on her face.

This idea of achieving a “mind of no mind” is very interesting. As mentioned in your statement: “A mind not preoccupied with emotions or thought”, is clearly a recurring factor throughout this body of work. However, would you ever consider photographing subjects that aren’t landscapes but with the same concept(s) of Zen?

When I speak of attempting to photograph with a mind not preoccupied with emotions or thought, I am speaking of simply photographing whatever I photograph whenever I photograph it and however I photograph it. It is an attempt to simply remove myself from all my expectations, emotions, concerns, anxieties, dreams, etc.— to remove myself, as much as possible, from the process of taking and processing the image. I just simply want to make photographs in whatever way I make them as I am making them. I emphasize that I “attempt to do this” because, as anyone who has studied Zen or practiced mediation knows, the self has a way of always interrupting everything one does, but one simply continues on with the process with all of its inevitable failures. This has become my practice.

At the risk of sounding foolish, I would say photography has become a kind of mediation for me. I enjoy the drive to wherever I am going. I enjoy the moment as it unfolds while I walk through a forest or along a shoreline or aim a camera at something. When I process, I open the photo up in Photoshop and just let my process, my practice, take me wherever it takes me. If I do not like what I have done with the photo when I am done, I simply delete it or save it in case I wander back in that direction some other day. Sometimes I start over; other times I move on. Some days, I end up with nothing that I think is successful. I am not bothered by it. All of it is simply part of the practice.

In addition to landscape work, I also photograph architecture, animals, flowers, structures, and very occasionally people, and I bring my practice to whatever I photograph. For me, this approach is essential. It helps me to live in the moment as fully as possible without worrying about whether the shot captures what I want to capture or if I could have done it better, etc. Why I am photographing, what I should photograph, when I should photograph, where should I take my photography, what photography means: none of these concerns and questions matter to me. I just do it. It is my practice.

I suppose that I can cultivate this approach because I do not make my living as a photographer. I do not need to worry about whether what I am doing will satisfy a client. I do not have to meet deadlines. If that was my life, then I would probably soon grow to hate taking images.

I often wonder where inspiration comes from, but, in the end, I have come to accept that I am grateful when it does come, and I accept those periods when the well of creativity is completely dry (sometimes lasting for quite a while). I will probably wander into other photographic journeys and genres but that will happen when that happens, or it will not happen.

For now, I continue my practice.

The balance of light and dark is obviously a very important structural decision within each photograph. However, do you aspire to evoke other feelings and emotions with projects like “Run off” and “Trees”, because of this dark and dramatic look?

If I am being entirely honest, I do not, as I have hinted in my previous responses so far, decide to do anything— at least not in the conventional sense of making a decision that comes from thinking about something, from analyzing something, and then making a choice to do something. I also cannot really know if any of my images evoke feelings and emotions in those that view the pictures. I do know that, as I said before, nature, in particular, evokes many feelings and reactions for me, but I am entirely uncertain about what others might feel. I do hope they will find the image worth looking at.

In the end, I think everything I do stems from what I have done before. To be more specific, I have been photographing for more than a decade now. When I first began, I thought about everything I did because I had no idea what I was doing or what I should be doing. Yet, I have never taken any classes or read any books or attended any workshops. Early on, I asked a few photographers questions about what ND filters to use so that I could make a reasonable choice of what to begin with, but I never asked how to do long exposure photography. I never asked anyone about infrared photography. I looked at a lot of infrared images and did not like them. I will confess I intentionally strayed away from the kitschy look of the overly whitish look of many IR photos. I just took long exposure and infrared and mostly black and white photos—and, to be honest, I took a lot of terrible photos. And through failure after failure, I learned how to take a reasonable image. I did not ask other people why my failures were failures. I just learned from my failures and the successes I saw in the work of others all on my own. This set me free in many ways— and provided me an opportunity to experiment with reckless abandon.

I never asked anyone how I should frame a photo. I just framed things in my photos. I looked at many, many, many images from established masters of photography, both living and dead, and many images from those, who like me, were learning how to make their own images. Eventually, I found my rhythm—and once I did, I stopped worrying about what I was doing and began to simply do it.

When I first opened Photoshop, I had no idea what to do. I did not take a Photoshop class. I did not read about Photoshop. I just used it. The same goes for any other software I use or used for processing. Once I had my basic skills down, I embraced the freedom of simply photographing. Other than trying to photograph silence, I have no specific goal in my mind. For me, the making of images is a practice, a process, a letting go and that is why I do it. I enjoy the opportunity to be creative and expressive. In interviews I have done in the past, I used to express some of my intentions and expectations. I no longer have any expectations or intentions (other than to attempt to photograph silence—which might not even be possible)

Keeping all of that in mind, I do not analyze the choices I make. The reasons why I use light and dark to create contrast is best answered by the fact that a lot of my images end up with those stark contrasts because that is the direction I often seem to head towards naturally. If I put aside my insistence that I simply do what I do because that is what I do, I can say the following: black and white images that have a lot of stark contrasts tend to be very dramatic. Those stark contrasts evoke, for me, a sense of silence. I would never expect anyone else to feel the way I do, but I often see the light in the image, the way it insists its presence, as an expression of silence. I am very surprised when someone comments on one of my particularly darker-toned images, saying the image is spooky. I do not see anything spooky. I see silence coming into the image through the light that insists its presence in the darker areas of the image.

I sometimes fear that I am very limited by my almost singular attempt to capture silence, but nearly every one of my images comes from this. I do not know if I am successful. Such determinations are left to those who view my images.

The use of long exposure is clearly an important tool during your creative process. “Minimalism study”, really highlights this bridge between landscape and abstract imagery. Do you intend to focus on future projects similar in approach to those of “Minimalism study” and “Sand”?

I still remember the first long exposure image I saw back in 2008 when I used to spend a lot of time looking at photos on Flickr (in fact, the Flickr community back in those days was a very important part of how I began to develop my long exposure work). It was an image of an island in a sea of misty haze and whitish water with the bright presence of the sun shining through the mist. I found it intoxicating. The photographer had chosen a palette of light grays and whites. It struck me as dramatic, mysterious, otherworldly, contemplative. I did not really know, at that time, what a long exposure entailed, but I was drawn to the beauty I experienced in that image. It fit my poetic sensibilities, my desire to find silence and solitude in my own life.

I was, however, convinced that the making of such an image could only be achieved by some kind of photographic alchemy. I waited at least a year until I tried to produce my own image. Back in 2008-2009, when I began to experiment with long exposure photography, there were no online tutorials (at least I had not found any). I still remember my very first attempt at taking a long exposure image. I completely misjudged the balance between the stops of the ND filter, the shutter speed, and the aperture size. The image was so overexposed that it was nearly pure white. However, I found it fairly easy to adjust the aperture and shutter speed by looking at how overexposed the image was (one of the great blessings of digital photography) and I came up with a reasonable image after another attempt (or two or three). When I look back through my archives now, I see hundreds of long exposure images that are quite terrible. In those early days, I was just taking long exposures because I thought it was cool to take long exposures—as if all that mattered was the fact it was a long exposure. I had no sense of what the “gimmick” of the process should yield. I was too enamored with the parlour trick, the mystery of it, the fact that one could leave a camera shutter open for seconds to minutes to hours (or longer).

Slowly, I managed to find a voice within the parlour trick, and it has become, as you say, an important part of my process for many of my images. I do not know how to explain it in plain terms, but there is something about the tonal quality that a long exposure yields which endlessly fascinates me. Long exposure images tend to be more malleable and shapeable when it comes to squeezing out the stark contrasts which I tend to produce in many of my images. I cannot imagine myself ever stopping— even though I do worry that it is overused and can easily be kitschy if not handled well. Also— I never grow tired of the fact that no matter how many years I have played with long exposure, I never quite know what to expect. Most of those times I expect it to look a certain way, but it often looks different than I had imagined it would. If nothing else, that sense of never knowing quite what you will get continually keeps the process interesting.

Minimalism is something else I have been drawn to for years. And by minimalism, I do not mean images that only have a few elements in them. For me minimalism is about images that have truly reduced a scene to a few simple elements (earth, water, sky, light), no focus on any solitary objects or small gathering of objects (though an object might still be present). Instead, they should focus on a merging of elements, a presence of elements, and not an isolated element. Images that focus on single objects are wonderfully minimal, but minimalism, for me, is about the creative spark that leads to capturing a truly simplified scene; a swash of water and light; a merging of water, cloud, and moon; water pouring over rocks in the warmth of a radiant light, or a swath of land leading to a horizon; all of these an attempt to capture a very thin slice of beauty. I think it is very important that one realizes the mood and expression of the photographer is truly missing in these scenes; in fact, there is or should be an almost concerted effort on the part of the photographer to remove him or herself. They are images that you create with no concern about your self-expression, one that you truly leave to a viewer to experience.

I cannot imagine that I would ever stop visiting and using long exposure (and infrared) to create and express whatever and wherever my practice takes me.

Your interest in Japanese traditions and application of Ikebana, Haiku and calligraphy seem to be a very important reference point for your work. Is travelling to Japan or a country whose values and traditions reflect those of the Japanese culture, something that you would potentially do for a future project?

I most definitely plan to travel to Japan someday. In fact, I am thinking about formally studying the language for a few years before I go so that I can more easily immerse myself in the culture. My interests in visiting Japan are not about photographing Japan, but I am sure I will definitely take many photographs. I am interested in visiting the many sacred structures and locations. I also would love the opportunity to finally meet, in person, one of my favorite photographers, Stephen Cairns— whose work and approach to photography I truly admire.

I started studying Ikebana three years ago. It has been very helpful in the way it has inspired how I compose. Much like my early years of photography, I had to learn what I was doing and, as a result, I made many mistakes (but this time I have a teacher). Ikebana is meant to elevate flower arranging to art, each flower arrangement being an individual art piece bound to the impermanence of the flowers that will soon wilt and dry. Arranging flowers as an artistic expression is not as easy as it might sound; in fact, it is very challenging. After three years of study, I think I am beginning to express something that is at least a little bit beyond sticking flowers into vases. I am drawn to the attention to asymmetry (asymmetry being its own harmony), to the balance of imbalance and the imbalance of balance. Ikebana, to oversimplify it, is very much about composition—and my eleven years of experience composing images has been very helpful to composing flowers—and, most definitely, composing flowers is having an influence on how I compose images. I have picked up many skills and tricks over the past few years for how to arrange and fix the flowers and branches so that they stay in place. I have learned about mass, line, color, negative space (or ma). And now, much like how I now approach photography, Ikebana has become part of my practice, part of how I live my life. I no longer think about how I am arranging the flowers. I just arrange them. I might fuss and switch things around, but I try to just do it, to just let it happen as it happens. I fail often. I simply continue the practice.

I occasionally write a haiku, but I am not very skilled at it. I have, however, read a lot of haiku. I have studied Zen Calligraphy through books and visits to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, but have not done any myself (though I hope to do so someday— perhaps after I have studied Japanese for a few years, so I will know more about kanji). I have been trying to learn how to grow Bonsai as well (which has had an influence on how I photograph trees— and how I photograph trees has influenced how I shape my bonsai trees). I also garden, merging the Japanese approaches I have studied with the Western approaches I have grown up with (I used to be employed as a gardener many years ago). Gardening also influences how I compose images— and how I compose landscapes has influenced how I garden. But I should stress that I do not consciously and/or intentionally incorporate these elements. They have all become part of who I am, part of my practice.

In other words, if asked to explain or teach how I approach my image-making, I often grow silent because I do not have a specific process; I simply do what I do when I do what I do. Several of my friends have asked me to participate and teach in one of their workshops, but each time I have, so far, either declined or never gotten around to it because I cannot imagine someone paying me money to tell them, “the secret to good image making is to go out and experiment and make images and learn from what works and what does not work” and “photography has everything to do with what you have seen and learned in your life, so make sure that you continue to see and learn— look at lots of photos, read poetry, watch movies, go hiking.”

I’d like to finalize by asking you about the importance of black and white itself. Many of your projects including this one display a very good technical application of black and white. Do you believe that by reintroducing colour to a piece you would lose the essence of balance that you have achieved thus far?

Several years ago, I was invited by Canadian jazz musicians David Braid (piano) and Phil Nimmons (clarinet) to show my photos on screens in a jazz club in Ottawa as they improvised while looking at those images. After the performance, I was asked to join them on stage to answer questions from the audience. I was asked why all the images I chose were black and white. I was silent for a moment because I felt compelled to offer a meaningful answer (something more than “I do because I do”). I smiled to show my awareness that I was taking a little too long to answer the question and then said: “Because truth resides in the blacks and whites.” The concertgoers chuckled because obviously my answer was not enough, so I continued to explain and said that I see the world in color; therefore, I do not wish to capture the world in the way that I see it. Those moments belong to those moments when I experience them. When I work on an image, I work on something entirely different than what I saw or what I see. I am not interested in capturing the world as it is. My eyes, our eyes, can see that whenever we wish. Whatever it is I am doing and however I am doing it, I do not wish to recreate what was or what is.

In the spirit of offering a more straightforward response, color photography is quite different than black and white photography. I have quite a few color images, but I do not share them very often because I do not feel I have found an adequate way to express myself in color. I am more naturally drawn to express myself in the stark contrasts of monochrome.

So, to more directly answer your question, I think reintroducing color to my black and white images would not work very well. In however I processed when I processed, black and white was the direction I naturally went. It is where I tend to naturally go.

I would like to end by expressing my gratitude for asking such interesting questions. I hope my responses do not seem like I am dodging their intent. I really appreciate the opportunity to think about such engaging questions. As each year passes, my thoughts about photography— as I become more and more comfortable with achieving a “mind of no mind”— seem to be fading more and more into the silence I attempt to photograph. Also— I wish to thank everyone at Dodho for always being so kind to me. I am both humbled by and grateful for the generosity.

Francesco Scalici

A recent MA graduate from the University of Lincoln, Francesco has now focused on landscape photography as the basis of his photographic platform. An author for DODHO magazine, Francesco’s interest in documentary photography has turned to writing and has had various articles, interviews and book reviews published on platforms such as: ‘All About Photo.com’, ‘Float Magazine’ and ‘Life Framer Magazine’. Currently on a photographic internship, Francesco has most recently been involved in the making of a short film titled: ‘No One Else’, directed by Pedro Sanchez Román and produced my Martin Nuza.