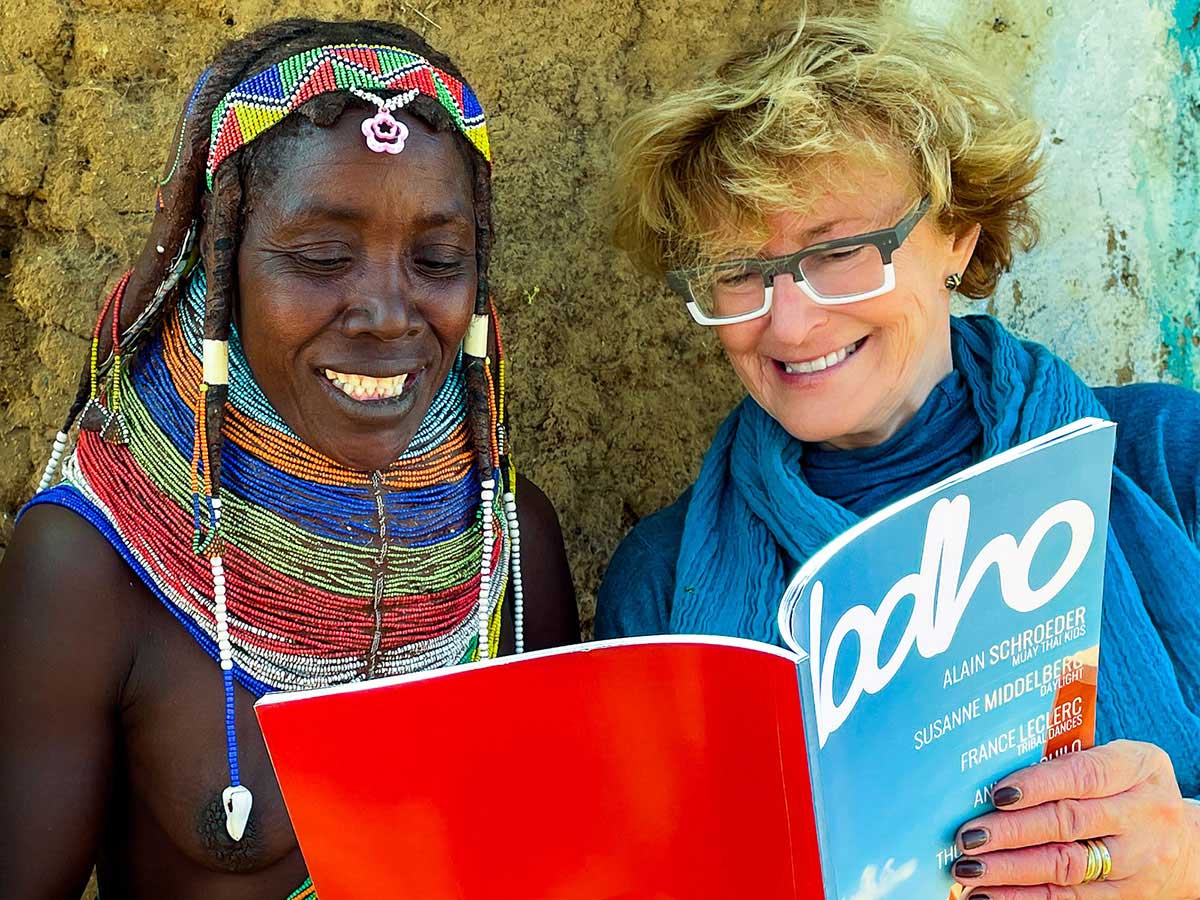

France Leclerc, born in Québec, Canada, is an independent photographer who currently lives in Chicago. Her early career was in academia, but her true passion for documentary and street photography has now taken over.

Among her most prominent themes are culture (especially vanishing ones), gender, and social inequality. She has been traveling around the world documenting people’s lives in diverse settings, often in out-of-the-way places. She often describes her work simply as “life photography” as her focus is always on people. [Official Website][Printed Edition][Digital Edition]

This body of work is very heart warming, I love how expressive the dancing is and how each photograph gives a feeling of soul and energy. I would like to know a little bit more about your experience while photographing each tribe and curating this collection of images?

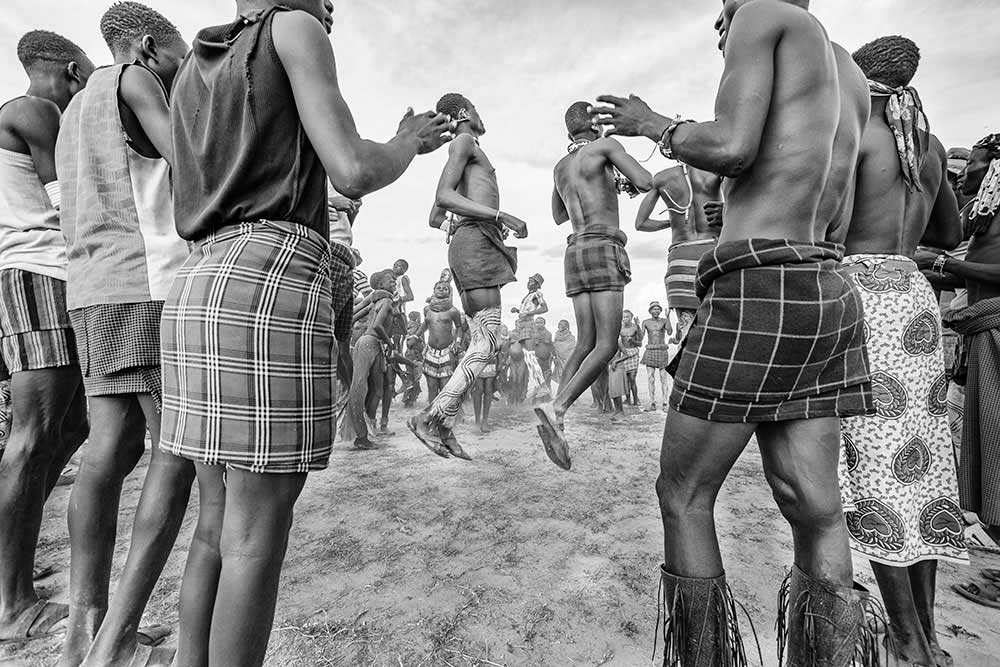

I think the immense joy the dancers experienced while dancing has stayed with me over and over. Life is quite challenging for these tribal groups; people work hard all day to survive. Dancing and music are their only distractions (though cell phones are now appearing in some tribes, they are still not providing entertainment), and of course, dancing has an important spiritual aspect. One has the feeling when it starts that the dancers are transported somewhere else. They seem to feed on one another, looking at each other, smiling, making their best moves not for me but for themselves. They lose themselves to the dance once it starts. And the beauty of it all is that it is very inclusive: everyone is invited, and children learn to react to the rhythm and are delighted to join. I often get quite emotional watching them, as I see them transform in front of my eyes– so different than how they were earlier in the day.

You mentioned in your description about each tribe and the various dances that to your eye they all seemed to have a pattern or similarity in rhythm and music. What would you say was the most similar element that connected each tribe in dance and music?

I am sure these various dances are quite different to an informed eye. There are detailed descriptions written by scholars on how each one is unique to a tribe as a function of a wide range of factors: physical location (forest dwellers dance differently than riverine people), daily activities (working movements feed into styles of dances), whether it is done as a group or as a solo dancer, whether they are in line or circles, etc. The point I was trying to make is that for an observer, particularly a foreigner, it is the percussive rhythms, sometimes created on locally-made drums, but often just made by singing and clapping hands, that gets my feet moving whether I want to or not. That feeling is the same way every time. And the movements are all quite simplistic and repetitive (except for the high jumping, I suppose, which I am never tempted to emulate). Also, three of the tribes I photographed (the Turkana of Kenya, the Toposa of South Sudan, and the Nyagatom of Ethiopia ) are Nilotic ethnic groups (people indigenous to the Nile Valley.) They are probably part of the same «cluster» of people who split because of internal differences at some point, eventually creating distinct, independent groups. This could explain why some of the dances felt similar to me, at least at a superficial level.

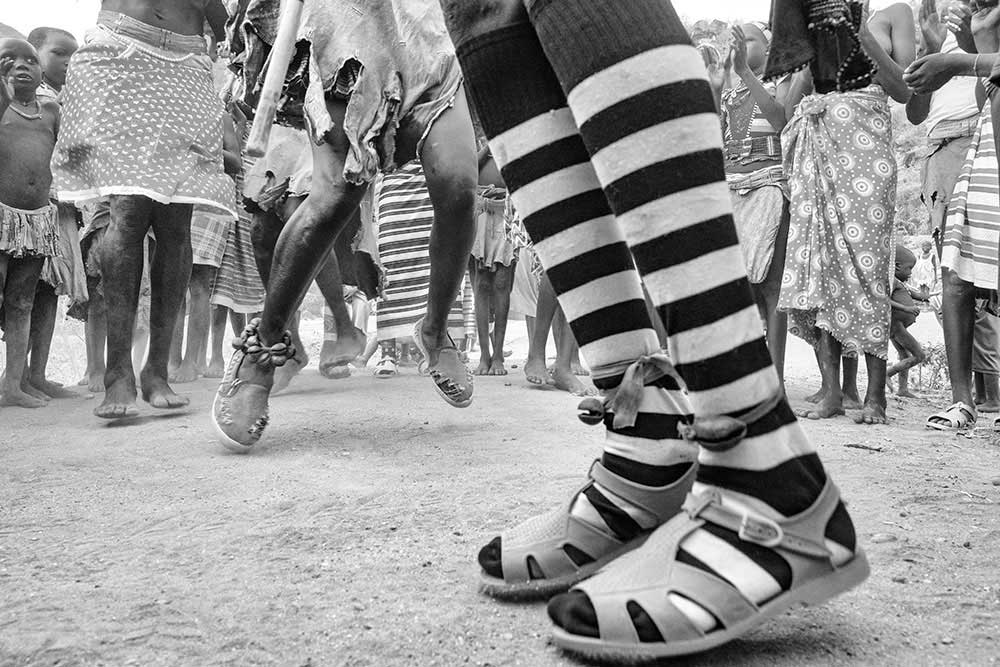

Aside from the fact that many of these dances have been traditions for many years, one point that I found quite interesting was how each tribe has managed to keep western culture and influences out. I was curious to know a little bit more about the accessories that occasionally showed up… something which you also mentioned in the magazine, and I though was quite a good insight and observation! Did you ever feel that some of these accessories were used to individualise some of the members, maybe adding to their personality or specific character trait?

Of course, as we do, they used «accessories» to stand out from their peers and, to some extent, to convey that they have (or had) a connection with the «modern» world. For example, in South Sudan, some Toposa men were drafted to fight in the war and returned to their village with boots. One would assume that boots became a prized passion for their comfort and functionality. However, some boys who do not have boots will paint their legs up to their knees to simulate them. Also, some of these accessories are used for different functions. The Toposa women proudly use their newly acquired whistles while dancing as a way to mark tempo and lead the women in a queue. The Wodaabe, a tribe in Chad, sew the colorful whistles to their clothes as an additional ornament to their already vibrant outfit.

And of course, like for us, some of these accessories come in and out of fashion depending on availability. When roads were built in Ethiopia, some tribal groups managed to acquire bright orange safety vests. The year I visited, many of them were wearing these vests to dance. And of course, bras are the new thing for women, but they are rare and a luxurious object. This past year, I have also seen socks a fair amount, and I have to say that the bold striped socks from one Larim woman made quite a statement. I think I better stop here; I now feel like a fashion critic.

What would you say was the most impactful image you shot? A photograph that really resonates with you and that you believe captures the spirit of a tribe or person.

It would be presumptuous of me to discuss the impact of one of my images on others. But I can speak to the image that resonates the most with me. It is probably the photo of the Suri tribe. Quite frankly, I am not sure whether it is the image per se or because I can recall the event surrounding it quite clearly (a problem all photographers have, separating the story and feelings associated with the photo and the photo itself.) The Suri dance was done to commemorate the death of two prominent tribe members. It was a sweltering and humid day, and the entire village was dancing. They were going around in a circle for hours, with occasionally one or two people dancing in the middle of the circle. I remember feeling that it was not physically possible to be going on for so long, and yet they kept at it, close to one another, humming a song. At one point, we heard a loud noise which I thought was probably someone with a drum. The noise got repeated a few times, and we realized that there were now shooting their AF-15 rifles in the air. At that point, we thought this was a good time for us to leave.

As to which photo best capture the spirit of a tribe, I sincerely think they all do. I like the photo of the Toposa women roaming around their village in a queue. I photographed them during a wedding celebration we ran into unexpectedly (but happily). They basically danced and followed the groom in his pretended attempt to find the bride in the village. The Toposa women are strong, determined, and supportive of one another; for me, this is so clearly shown in this image.

I would like to know if at any point you were invited to dance with members of the tribe and join in the festivities and celebrations? Also, were these dances a kind of daily routine or do the dances serve a specific function in the community.

These dances can serve many functions in the community, to celebrate, communicate, mark a rite of passage, as ritual ceremonies, or just relaxing after a hard day. As I said earlier, one of the Toposa images in the set was to celebrate a wedding; one was for commemorating the departed, and others were explicitly for thanking us as we typically bring food for them.

As for joining in, everyone is always invited to participate. I join in with a few dance steps from time to time, but I mostly try to photograph (and it is hard to do both at the same time!). Of course, they are delighted if you dance along with them and are very supportive of your (embarrassing) efforts.

I would like to conclude this interview by asking you about future work and if you are planning on visiting these tribes again and continue documenting these beautiful dances?

Yes, and yes. It is likely that I will revisit at least some of these tribes. I have also been traveling to West Africa lately, namely Ivory Coast, Togo, and Benin, where the dance and music cultures are quite different from East Africa, but also very vibrant. And I am just back from Angola, where dances are somewhat reminiscent of the ones performed by the Maasai. I hope that these traditional dances survive the impact of the modern world, I feel that I am in a race against time to see them.

Francesco Scalici

A recent MA graduate from the University of Lincoln, Francesco has now focused on landscape photography as the basis of his photographic platform. An author for DODHO magazine, Francesco’s interest in documentary photography has turned to writing and has had various articles, interviews and book reviews published on platforms such as: ‘All About Photo.com’, ‘Float Magazine’ and ‘Life Framer Magazine’. Currently on a photographic internship, Francesco has most recently been involved in the making of a short film titled: ‘No One Else’, directed by Pedro Sanchez Román and produced my Martin Nuza.