If you drive south from Los Angeles on Interstate CA-111 along the eastern shore of the Salton Sea, past Bombay Beach, Frink, Wister, Mundo, and around the migrating geyser, you’ll reach Niland, one of the poorest counties in California.

Turn left at Mae’s grocery on Main Street and head east over the Southern Pacific railroad tracks, until Main becomes Beal Street access road. On any given day you might pass Cuervo, as tall and lean as a scarecrow, riding his mule to town. He sits in the shade of the United Food Centre drinking cheap whiskey and popping oxycontin pills.

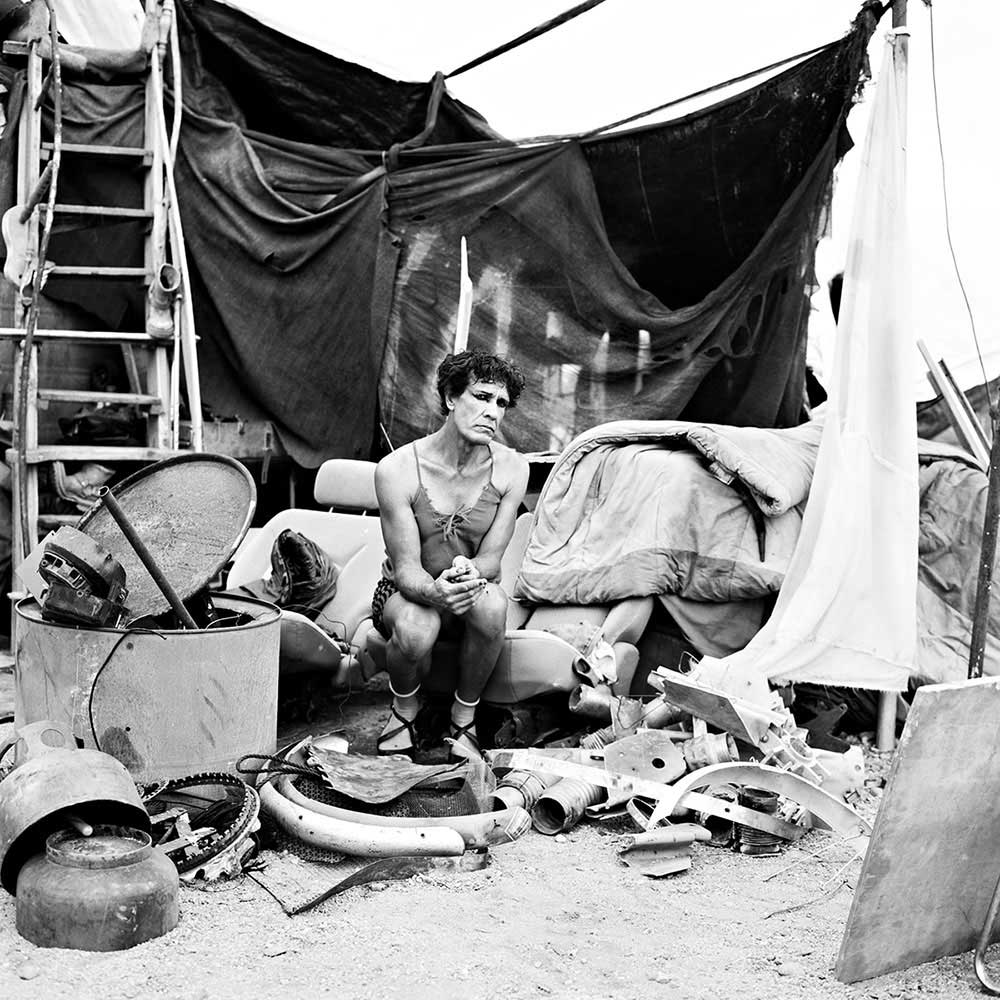

Slab City is your destination, an off-grid community in the Sonoran Desert, and Cuervo might well be its living image: the hard-luck American cowboy on his steed, wandering by his whims, putting down shallow roots. Live and let live rules this desert squat. Be neighbourly, follow the ethics guide, and do unto others. It is both America the Great and the toxic end-product of American capitalism — those who couldn’t work and live within the system and those who outright rejected it.

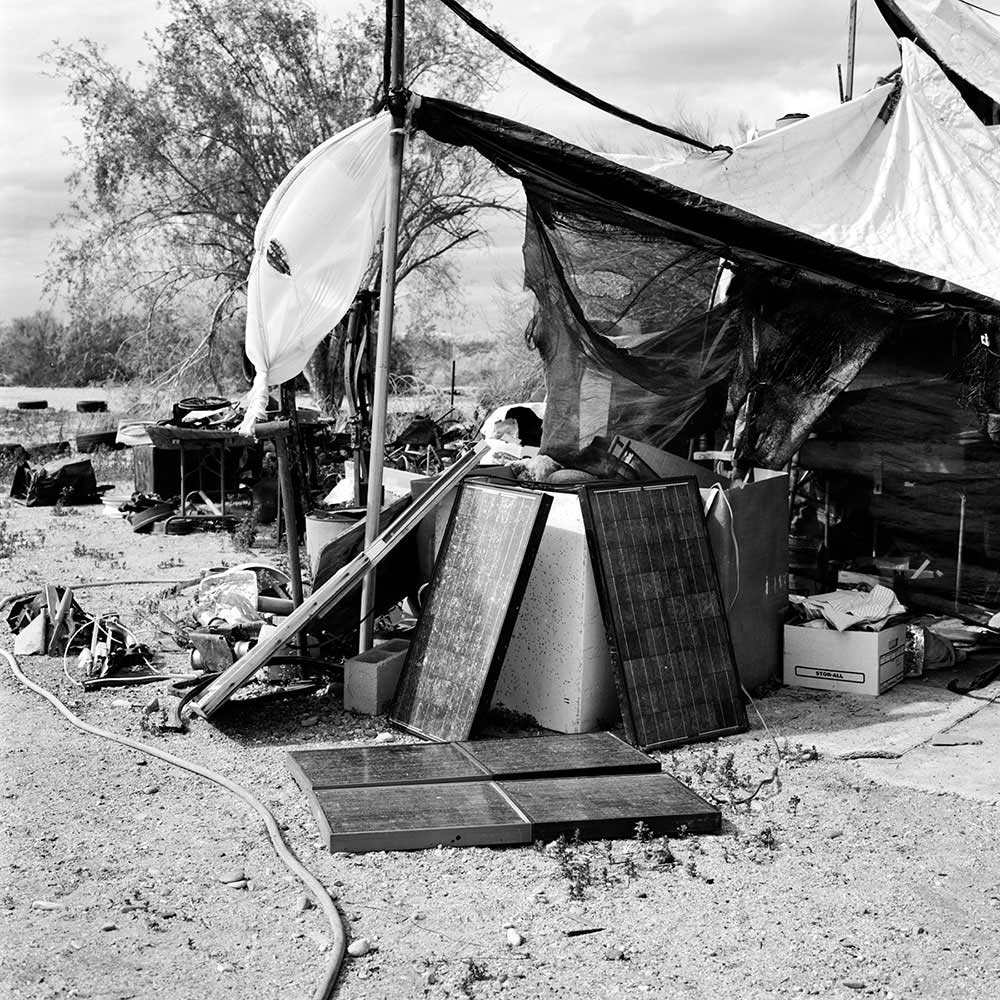

Just past the East High Line Canal you come to a sentry box painted in psychedelic colours by Noah Achram, an electrician’s apprentice-turned-artist from Detroit. Hop out and feel the searing desert heat that melts plastic. Ahead on your left you’ll start seeing camps. In late spring small rocks and soup cans roughly mark camp boundaries, but it’s too late in the season for most camps to offer much protection. Nearby recreational vehicles sit stolidly, out of place. Like birds late to migration, their owners will soon flee the heat in their air-conditioned rolling homes, returning to Babylon (city life) and cooler weather in the north. They’ll be back with winter.

Towering over all of this is Salvation Mountain. Leonard Knight’s fifty-foot-tall technicolour hillside installation brings thousands of tourists — and their dollars — through to East Jesus, the art colony created by Charlie Russell (a.k.a. Container Charlie). Knight began the project in 1984 and spent the rest of his life rebuilding his vibrant, cartoonish tribute to God after it collapsed in 1990.

Between Salvation Mountain and East Jesus lies Slab City proper. When you arrive at the second sentry box, you’re in The Slabs. Welcome to the Last Free Place! You’re entering a 640 acre plot of California desert situated between the Salton Sea in the west and the Chocolate Mountain Aerial Gunnery Range to the north.

Slab City sits on the leftover infrastructure of Camp Dunlap, a WWII Marine base activated in 1942 as a training camp for action in North Africa. The base also provided training areas for army troops under General Patton, a bombing range for planes from a nearby Marine Air Station, and a staging area for smaller Marine groups. It was deactivated in 1945. When the land was returned to the state, only the concrete slab foundations remained to float on the shifting sands.

Slabbers have been shifting with these sands for decades; building, scrapping, repurposing, surviving, dying. The year-round population is modest. Roughy 50 residents stay through July and August when even rattlesnakes seek the shade of

campers. Every year a few are lost from dehydration or overdose. A shared distaste for the gridded boilerplate of city life prevails, and spurs this free range society of feral folks to endure withering conditions season after season.

You might imagine them as modern American pioneers, with a variety of reasons for coming here and staying. Many are transient, coming for the warmth in winter. Some seek anonymity, others to forego the rat race. Veterans with PTSD neighbour hippies, artists, and musicians. Survivalists and religious men come to the desert to test themselves. Those skirting the law hide deep in the Slabs under cover of creosote, next to seemingly average American families who never quite recovered from the Great Recession.

Camps range from desert comfort to simple A-frames made of cardboard and solar panel pallets. There are Slabbers in WWII bunkers, recreational vehicles (which, themselves, vary widely in quality and comfort), hostels, the Christian Centre, water cisterns, school buses, and underground. Prime space within the Slabs is scarce and built-up camps are often sold when people leave for the city. Some become imprisoned by their freedom, unable to leave their camps for long, afraid of petty thieves and camp pirates.

Few enjoy the conveniences of modern urban living. There is no free drinkable water, no tap to turn. Slabbers can filter the East High Line Canal, brown with farm runoff, or take from the faster moving Coachella Canal feeding Palm Springs and Los Angeles. Otherwise, you pay local suppliers. Garbage is either kept by Slabbers (for future reuse) or dumped for lack of municipal pick-up. Solar panels and deep cycle batteries provide power for fans and swamp coolers in the hottest months. Sanitation varies from RVs to composting toilets and gopher holes: to each his own. There is a cost to living free.

Nothing is certain in this landscape, but friends and neighbours offset the vicissitudes of desert living. Mojo’s camp offers free clothes and water and the Niland Chamber of Commerce hands out basic food staples once a month. The Internet Cafe dispenses free coffee and wifi. The Oasis Club provides mail service for anyone without a P.O. box in nearby Niland, as well as a five dollar Sunday breakfast. Behind the Oasis, the Wayside Inn hosts a weekly fish fry and daily meals, The library is a well-stocked respite from the heat and has its own bar. On Saturday night, Slabbers converge on Builder Bill’s Range to catch up and listen to live music late into the night.

It remains to be seen whether comradery alone can save the Slabs and prevent it from becoming another geothermal plant like the ones dotting the shores of the Salton Sea. Slabbers are technically squatting on state land, originally mandated to the local school board.

Slab City is a container for the ill, impoverished, and outcast. What would the state do for these people if their home became a solar panel farm or an extension of the nearby military training base? Where would they go? Here, at least, they have a certain leverage in a county plagued by high unemployment and few opportunities; Niland’s economy depends on Slab City and the local markets that service it. Salvation Mountain brings in tens of thousands of tourists dollars annually. It’s a nice day trip from Los Angeles.

Many Slabbers view the potential sale of their land as the most pressing threat to their way of life. But they tend to worry more about local usurpers and an internal coup than they do about Slab City being squashed by state muscle (not entirely unreasonable given how difficult and costly it would be for the state to raze the Slabs and rehabilitate the area for commercial use). They want freedom or nothing, regardless of who plays landlord. It’s why many of them came here in the first place.

And looming ownership struggles are far from the only struggle. Like Camp Dunlap before it, Slab City continues to generate significant waste (human and industrial), making clean-up costly, if not impossible. And the Slabs sit well within the circle of a dangerous ecological disaster — the Salton Sea. As the “sea” (actually a lake) evaporates and recedes, it exposes thousands of acres of toxic mud which contains arsenic, selenium, chromium, zinc, lead, and pesticides like DDT. Powerful desert winds spread these toxins as far as Los Angeles, significantly affecting air quality and health outcomes in the immediate area.

Constantly balancing one peril against another, the resilience of this community is unquestionable. Shallow or not, it’s hard to bet against roots like that. For those who call the Slabs home, the Last Free Place will likely remain that way for the foreseeable future.

About Daniel Skwarna

Daniel Skwarna is a multi-award winning documentary photographer and published writer. His personal work explores isolated communities, addiction, and mental illness. He has worked in the United States, Iceland, England, Scotland, Ireland, Cuba, Turkey, Israel and the West Bank, Greece, France, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Serbia Croatia, Bosnia & Hercegovina, Kosovo, Slovakia, Sarajevo, Poland, and Russia.

Daniel attended the University of Toronto and holds a degree in History, Fine Art History and Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations. Select commercial and editorial clients include: Apple, BDC, Celestica, Mercedes-Benz, Invesco, Report on Business, Fortune Magazine, Spacing Magazine, Beside Magazine and the Globe & Mail.

Recent awards include: Applied Arts, 2021 Lensculture Portrait Award Finalist, and American Photography 37. He lives in Toronto with his wife, Sarah, and daughter Lumen. [Official Website]