Greenland is, undeniably, suffering the effects of climate change. And over the last few decades, its society has undergone profound evolution.

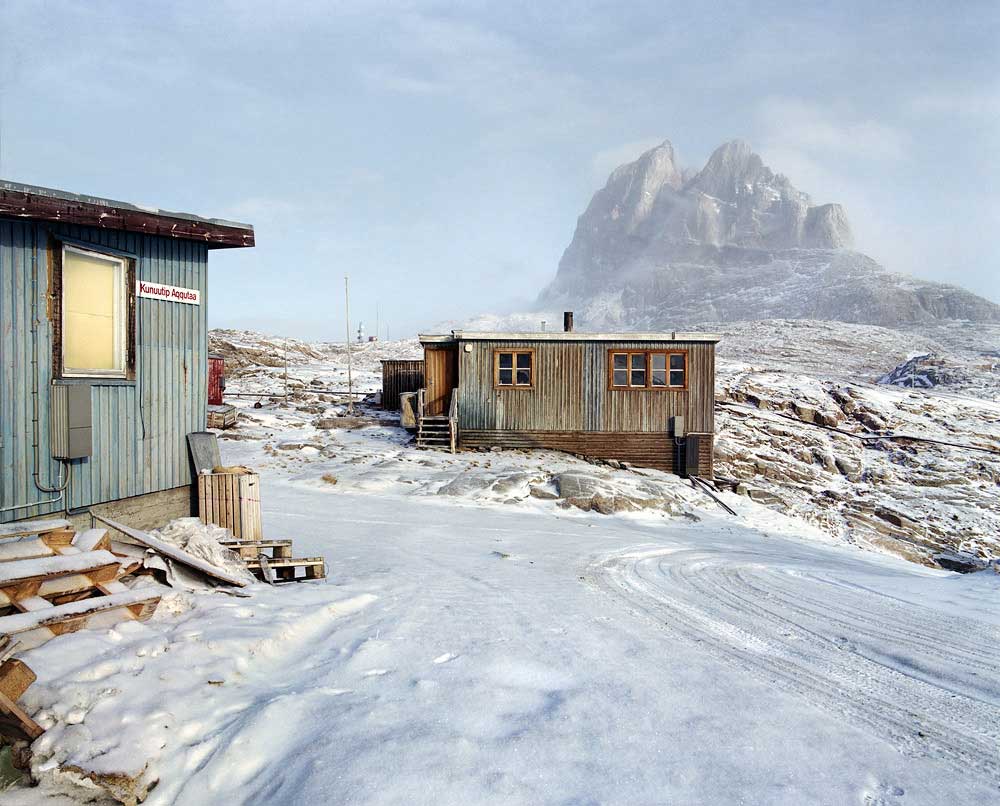

Thus, as the environment shifts, its people begin to embrace Western lifestyles and modes of consumption in parallel. Supermarkets, churches, cell phones or Facebook are slowly making their way into Inuit culture.

For the teenagers in the major towns the memories of seal hunting trips are long gone. And when they still occur in the northernmost dwellings, the traditional outfits made from animal hides mix with modern fabrics, and boats are used in combination with sledges. Tradition and technology are blending together, and the extent to which lifestyles differ on this territory is considerable.

Sébastien Tixier has always been fascinated by those who choose to live in hostile environments, especially in the remote lands of the North, as some of his childhood memories involve stories of Inuit men and women living on the ice, hunting seals using age-old techniques. The preparation process lasted for a period of a year and a half, during which the photographer immersed himself in the country’s history and current affairs, spotted locations, made contacts for his stays, and grappled with the charming grammar of the Inuit language, Kalaallisut. When he then traveled to Greenland at the beginning of 2013 he stayed with the local inhabitants of both some expanding “western” towns and the northernmost dwellings he encountered. From modern houses to nights in a tent pitched on the ice after hunting seals.

The results of this project are photographs which combines both a meticulous approach and an unremittingly instinctive feel. Despite the thorough preparation, the photograph admits he had felt like a foreigner when confronted with the originality of the environment, and with the challenges induced by the harsh conditions in which a simple breath freezes instantly on a viewfinder. This appears to come across in the wider framing of certain images, as if he felt compelled to take a few steps back in the snow to include ever-more context. Yet at other times, on the contrary, he gets closer to his subjects to provide more details and clues.

His journey brought him from the 67th to the 77th parallel north until Qaanaaq, with the aim of recording these changes on film, and confront today’s reality with childhood tales’ clichés: it’s not just about the pure white landscapes, the socio-economic questions currently rocking the nation are of everyone’s interest. These radical and rapid changes raise questions about society and identity, and divide public opinion in Greenland. Its people are torn between a desire to catch up with the modern world, and a feeling that they are an ice population which, like the ice itself, is slowly melting away.

Allanngorpoq” in Greenlandic can be translated as “being transformed

Medium-format analog photographs, 2013

About Sebastien Tixier

Born in 1980 in a small town in central France, Sebastien Tixier now lives and works in Paris. Trained as an engineer, but fascinated by his father’s camera during his childhood, he finally became a self-taught independent photographer in 2007. His work ranges from staged studio photographs to landscapes and documentaries on globalization and its impacts – culture, environment. His photographs have been awarded numerous prizes and been exhibited in festivals and galleries across Europe.

Allanngorpoq, his latest work to date, synthesizes a year and a half of preparation (documenting, making contacts, and learning the language) and immersion in Greenland. This artistic photo report captures the evolution of both a changing territory and its people. The book of this work was published in December 2014 and develops in 60 photographs. It is prefaced by Stéphane Victor, son of the famous arctic explorer and ethnologist Paul-Emile Victor. [Official Website]

The town provides its inhabitants with the same services as any regular Western town, and con- tinues to expand and grow, close to the luxurious Hotel Arctic on the hills above the harbor. Fishing is one of the main activities in Greenland, and its industry is the country’s second largest employer after the public sector. Ilulissat’s harbor is one the biggest platform for this activity. The production provides the supply for the shops in town, but is also widely exported. Fishing exports for Europe, USA and also Japan now come for almost 90% of all Greenland’s exports.

While the Inuits historically embraced Shaman- ism, Danish colonialism introduced the Protestant monotheistic religion to Greenland.

Cemeteries are usually located on the outskirts of town. Crosses sit atop the graves, and cold-resis- tant plastic flowers are used as decorations.

After the camp has woken up, it is time to fill the water bottles with drinking water. Hunters cut ice blocks from the icebergs stuck in the sea ice, and let them melt over a camping stove. The hunt will only starts at nightfall, and until them the jour- ney must continue further on the sea ice until the extremity is reached.

While running water is still lacking from many houses in the far north, modernity is nonetheless making its presence felt: telephones and even televisions are now part of everyday life. And while many houses in the north of the country also do not have access to a developed sewage system (wastewater flows from homes and freezes in the streets), toilets are, however, serviced by a spe- cialized municipal collection team. These new jobs reflect Greenland’s quest to secure its own financial independence as it embraces a more Western lifestyle.

After a seven-hour journey from Qaanaaq we meet another group of hunters already there. “Siku a jor- poq” says one of them : “the ice is bad”, we have to move and look for another place. Cell phones are used frequently, as is the case here, to keep abreast of the shifting weather – a telltale sign of the changing times. (Remark: here the hunter is having a call to Ikuo Oshima, a famous Japanese hunter who settled in Siorapalukin 1972)

View from the edge of town, at the 77th north par- allel, facing South – where the rest of the world is.