If street photography was born with the portability of the Leica, its consolidation took place at the turbulent heart of the twentieth century.

Urban modernity, industrial expansion, and the accelerated transformation of cities created the ideal setting for a practice that required human density, social friction, and constant movement.

In Paris, figures such as Brassaï and André Kertész explored the nocturnal city and its margins. Brassaï transformed 1930s Paris into an almost theatrical territory populated by shadows, prostitutes, lovers, and night workers. His gaze was not purely documentary; it was atmospheric, almost literary. Kertész, on the other hand, introduced a more intimate and poetic sensibility, where formal composition entered into dialogue with everyday life.

French humanist photography, also represented by Robert Doisneau and Willy Ronis, focused on the emotional dimension of the street. The city was not merely a stage of tension but also a space of tenderness and humor. This tradition established an optimistic narrative deeply tied to the shared experience of public space.

In the United States, the evolution took a different direction. Walker Evans had already incorporated a detached frontal approach that contrasted with European sentimentality. But it was Robert Frank who definitively fractured the narrative. With The Americans, published in 1958, the street ceased to be a harmonious environment and became instead a space of contradiction, solitude, and inequality. Street photography adopted a critical and existential tone.

Garry Winogrand pushed that rupture even further. His images appeared disordered, tilted, tense. Classical composition gave way to an almost chaotic energy that reflected the complexity of American urban life in transformation. The street was no longer simply a site of observation; it was a field of forces.

At the same time, photographers such as Diane Arbus directed their attention toward marginalized figures, expanding the boundaries of visibility and questioning the limits between street photography, portraiture, and documentary practice. Helen Levitt, with her quiet focus on childhood and spontaneous gestures in working-class neighborhoods, contributed a more intimate and restrained dimension.

As the century progressed, street photography gradually abandoned the illusion of neutrality. The camera was no longer an invisible tool but a conscious instrument of interpretation. The influence of collectives such as Magnum Photos helped legitimize the practice within both artistic and journalistic discourse on an international scale.

In the 1970s and 1980s, color entered the field with force. Joel Meyerowitz and William Eggleston demonstrated that street photography could move beyond black and white without losing depth. Everyday banality acquired symbolic weight through saturated color and attentive observation.

The twentieth century did not produce a single definition of street photography. It produced multiple tensions: between formalism and chaos, empathy and distance, document and personal expression. That plurality is precisely what allowed the practice to survive technological and cultural shifts.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, street photography was no longer a territory defined by a single aesthetic. It had become an open tradition, a language in constant negotiation with its context.

Street Photography vs Documentary Photography: Key Differences and Overlaps

Street photography and documentary photography are often used interchangeably. Both operate in public spaces. Both engage with real people. Both claim a relationship with reality. Yet they are not the same practice.

Understanding the difference between street photography and documentary photography is essential to understanding the evolution of contemporary visual culture.

At first glance, the distinction appears simple: street photography captures spontaneous moments in public space, while documentary photography investigates broader social realities. But the boundary is more nuanced.

Intention and Duration

Street photography is typically driven by immediacy. It is rooted in the encounter, in the fleeting interaction between photographer and environment. The photographer reacts to what unfolds, often without prior research or long-term planning.

Documentary photography, by contrast, is usually project-based and sustained over time. It involves investigation, immersion, and narrative construction. The photographer enters a subject with purpose and builds a coherent body of work around it. Street photography thrives on the fragment. Documentary photography constructs context.

Relationship with the Subject

In street photography, subjects are often unaware of being photographed. The relationship is distant, sometimes anonymous. The image emerges from unpredictability.

In documentary photography, especially in long-term documentary projects, there is often interaction, dialogue, and sometimes collaboration between photographer and subject. Trust becomes central. Street photography captures presence. Documentary photography develops relationships.

Narrative Structure

Street photography does not necessarily aim to tell a complete story. A single image may function independently, open to interpretation. Ambiguity is part of its strength. Documentary photography tends to build structured narratives. Even when individual images stand alone, they often belong to a broader visual argument. One suggests. The other explains.

Ethical Framework

Both practices raise ethical questions, but in different ways.Street photography deals with spontaneity and consent in public space. The ethical tension lies in visibility and vulnerability.

Documentary photography carries additional responsibilities: representation, context, and long-term consequences for subjects.The ethical weight in documentary photography is often sustained. In street photography, it is instantaneous.

A Fluid Boundary

Despite these distinctions, the line between street photography and documentary photography has become increasingly fluid in contemporary practice. Photographers such as Bruce Davidson blurred the boundary by combining candid urban imagery with sustained documentary engagement. Others move freely between both territories, using street encounters as entry points into larger social narratives.

In the digital era, this distinction becomes even more complex. Many contemporary photographers construct long-term projects from street observations, gradually shifting from spontaneous capture to structured documentation.

Street photography and documentary photography should not be understood as opposites. They are adjacent languages. One privileges the immediacy of the encounter; the other privileges sustained inquiry. Both attempt to articulate how individuals inhabit shared space. Understanding their differences does not divide them. It clarifies the intention behind the image. And intention remains the defining element in both practices.

Techniques in Contemporary Street Photography

Street photography has never been defined by equipment. It has always been defined by attention. Yet behind the apparent spontaneity of a strong street photograph lies a set of techniques that shape how the world is seen and captured.

Contemporary street photography may appear instinctive, even accidental, but it is often built on discipline, repetition, and a refined understanding of visual mechanics. Technique does not replace intuition. It sharpens it.

Zone Focusing and Pre-Focus Strategy

One of the most enduring technical methods in street photography is zone focusing. Popularized during the era of manual rangefinders, this technique involves setting a fixed focus distance and aperture in advance, allowing the photographer to react instantly without waiting for autofocus confirmation.

By pre-focusing at a specific distance and using a mid-range aperture such as f/8 or f/11, photographers maximize depth of field. This enables them to capture decisive moments without technical hesitation. Zone focusing is not about speed alone. It is about anticipation. It requires reading space and predicting movement before it unfolds.

Layering and Visual Complexity

Strong street photography often operates in layers. Rather than isolating a single subject, photographers compose scenes where foreground, midground, and background interact simultaneously.

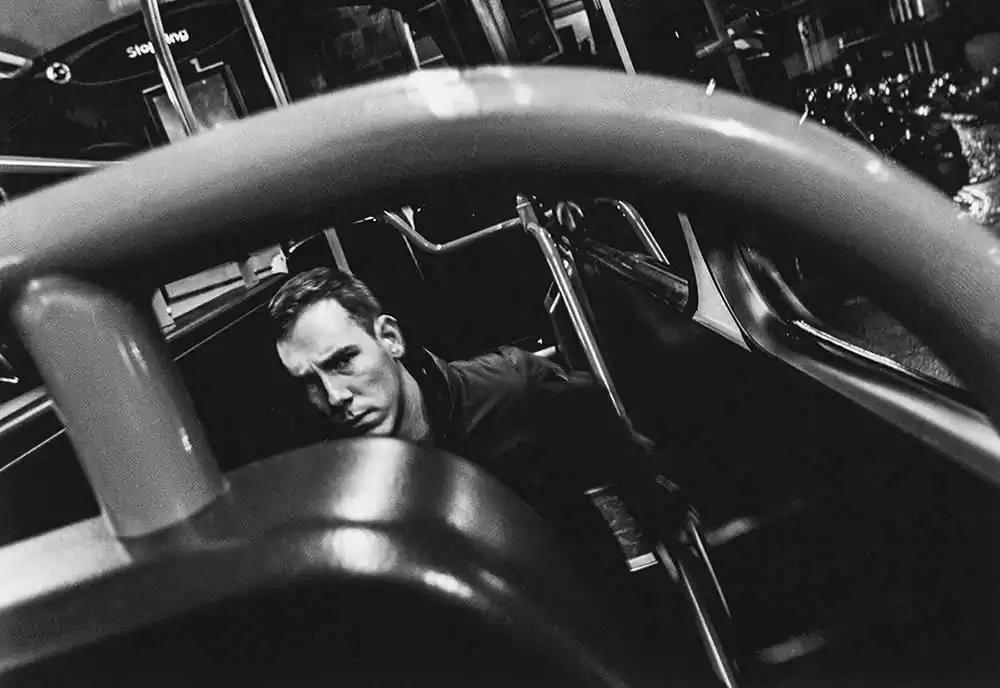

Layering introduces tension and narrative ambiguity. A passerby in the foreground may obscure another figure in the background. Reflections in glass may merge interior and exterior spaces. Shadows may function as independent actors. This complexity transforms a simple street scene into a dynamic visual field.

Working with Light and Shadow

Light in street photography is rarely controlled. It must be observed and exploited. Many contemporary street photographers do not chase subjects; they choose light first. They identify areas where sunlight cuts sharply across architecture or where shadows create natural frames. They position themselves and wait.

Hard midday light, once considered problematic, can produce dramatic contrast and graphic abstraction. Low light conditions can dissolve figures into silhouette, reducing identity to gesture. Light is not decoration. It is structure.

Shooting from the Hip and Invisible Presence

Discretion has always been part of street photography. Shooting from the hip, holding the camera at waist level without raising it to the eye, allows for candid capture without direct confrontation.

While modern autofocus systems make eye-level shooting easier, the principle remains: minimize intrusion, maximize authenticity. However, invisibility is often overstated. Many contemporary street photographers embrace visible presence, engaging openly with their environment. The technique adapts to context.

Reflections, Frames, and Urban Geometry

Urban environments offer built-in compositional tools: windows, mirrors, doorways, scaffolding, signage. Reflections allow multiple realities to coexist within a single frame. Framing through architectural elements can isolate subjects without isolating context. Geometry organizes chaos. In this sense, street photography often borders on architectural photography in its use of lines and spatial rhythm.

Movement and Imperfection

Not all contemporary street photography seeks crisp precision. Motion blur, partial figures, and obstructed views are increasingly common. Blur can communicate speed, anonymity, or emotional distance. Cropped bodies may suggest fragmentation. Imperfection becomes expressive rather than accidental.This shift marks a departure from the classical obsession with the perfectly timed gesture. Contemporary street photography often embraces instability.

Editing as Final Technique

The final technique is not executed in the street but in the editing process. Street photographers typically produce thousands of images to extract a few that resonate. Editing requires distance. It demands the ability to recognize patterns and eliminate redundancy.

A strong street photography project is not defined by the number of images captured but by the coherence of the selected sequence.Technique, in the end, is not about mastering equipment. It is about mastering attention, patience, and selection. Street photography may begin with instinct. It becomes meaningful through discipline.

Women in Street Photography: Expanding the Gaze

For much of the twentieth century, the canon of street photography appeared overwhelmingly male. The dominant narrative revolved around figures such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, and Joel Meyerowitz. Yet this apparent imbalance tells only part of the story.

Women have played a crucial and transformative role in the evolution of street photography, often bringing different sensitivities, access points, and ethical frameworks to the practice. Their contribution has not simply added diversity to the field; it has reshaped how the street itself is seen.

Helen Levitt and the Poetics of the Everyday

One of the earliest and most significant voices was Helen Levitt. Working in New York from the 1930s onward, Levitt photographed children playing in working-class neighborhoods. Her images are quiet, intimate, and attentive to gesture. Levitt’s street photography did not seek spectacle. It found meaning in small theatrical moments unfolding on stoops and sidewalks. Her work demonstrated that the street could be tender without becoming sentimental.

Diane Arbus and the Edge of Visibility

Diane Arbus occupies a more controversial position. Though often associated with portraiture, much of her work intersects with street photography in its engagement with public space and marginal figures.

Arbus shifted attention toward individuals who existed outside social norms. Her images forced viewers to confront discomfort. In doing so, she expanded the boundaries of what street photography could address.

Vivian Maier and the Anonymous Archive

The posthumous discovery of Vivian Maier’s vast archive added another dimension. Working as a nanny while photographing urban life in Chicago and New York, Maier produced thousands of images that combined formal precision with emotional ambiguity. Her work complicates assumptions about visibility and recognition within photographic history. The street photographer need not be publicly acknowledged to shape the visual language of a genre.

A Different Access to Public Space

Historically, public space has not been experienced equally by all bodies. For women photographers, navigating the street has involved distinct social realities. That difference of experience often translates into difference of gaze.

Contemporary women street photographers frequently address themes such as vulnerability, gendered presence in public space, and the subtle power dynamics embedded in everyday interactions. Rather than emphasizing confrontation or aggressive proximity, many adopt strategies of quiet observation, relational awareness, or collaborative engagement.

Contemporary Voices and Expanding Narratives

Today, women in street photography are not peripheral figures; they are central voices shaping the field globally. From Tokyo to Lagos, from São Paulo to Berlin, contemporary practitioners reinterpret urban life through perspectives informed by gender, cultural context, and personal history. Their work often interrogates the act of looking itself. Who has the right to observe? How does power circulate in the public sphere? How does visibility intersect with identity? These questions complicate the traditional mythology of the lone male photographer hunting decisive moments.

Beyond Representation

Including women in the history of street photography is not a matter of statistical balance. It is a matter of understanding how the genre evolves. Street photography is shaped not only by technique or equipment but by the social position of the person behind the camera. Expanding the field to include diverse voices deepens its ethical and conceptual range.

The street is not neutral. Neither is the gaze. As contemporary street photography continues to evolve, the contributions of women photographers ensure that the practice remains dynamic, self-aware, and open to reinterpretation.

Contemporary Street Photography Projects on Dodho Magazine

Street photography is not a closed chapter in photographic history. It is an evolving language, constantly reinterpreted across cities, cultures, and generations. The theoretical debates around spontaneity, ethics, authorship, and visibility find their most compelling answers not in definitions, but in practice.

Across more than 300 street photography projects published on Dodho, the genre reveals itself not as a fixed formula but as a flexible field of experimentation. Some photographers remain close to the classical lineage of black and white street photography, working with strong geometry, shadow contrast, and carefully anticipated gestures. In these works, the city becomes a stage of formal tension, where bodies align with architectural lines and fleeting expressions crystallize into structured compositions.

Others embrace color as a structural element rather than decoration. Saturated tones, artificial light, neon reflections, and chromatic clashes redefine the contemporary urban landscape. In these projects, color is not secondary to form; it is narrative material.

Street photography today also expands into experimental territory. Reflections fragment space. Layers multiply perspectives. Motion blur disrupts clarity. Figures are partially concealed, identities obscured. These approaches question the classical ideal of the decisive moment and embrace ambiguity as a central aesthetic strategy.

Geographically, the street is no longer defined by Paris or New York. Projects from Tokyo, Lagos, Kyiv, São Paulo, Berlin, and countless other cities demonstrate how local realities reshape the genre. Cultural codes influence proximity, confrontation, humor, and vulnerability. The street becomes plural, shaped by context rather than tradition.

In some works, the photographer remains an invisible observer. In others, presence becomes visible, acknowledged, sometimes confronted. The relationship between photographer and subject varies dramatically, reflecting evolving attitudes toward consent and public visibility in the digital era. What unites these diverse approaches is not style but attention. Each project published on Dodho that engages with street photography participates in an ongoing conversation about how we inhabit shared space.

The street remains a laboratory of human behavior. It exposes rhythms of daily life, micro-conflicts, silent gestures, and unexpected alignments. Through different techniques and sensibilities, contemporary photographers continue to test the limits of what street photography can be.Below, you will find a curated selection of street photography projects published on Dodho, representing different approaches, geographies, and aesthetic decisions. Together, they form a living archive of contemporary street photography.

Color Street Photography

Chris Yan: Capturing Beijing’s Soul Through Street Photography

Born in Beijing, photographer Chris Yan captures the soul of a city suspended between centuries. Through his lens, tradition and modernity collide in poetic harmony, revealing the silent stories of a metropolis in constant transformation… Read More

Street Photography Versilia by Salvatore Matarazzo

So Coney! by David Godichaud

John Kayacan and His Journey in Street Photography

Street Photography by Stephane Navailles

B&W Street Photography

Street photography; Stolen Portraits by Michele Punturieri

Fleeting moments in life captured in the most classic street-photography style over a decade ranging from 2008 to 2018. All around Europe. From Lisbon to Edinburgh, passing through Dublin, Vienna, Amsterdam, Madrid and the London Soho…Read More

Marrakech, the challenge Ignacio Santana

Marrakech, the challenge Marrakech, the magical red city of Morocco, is undoubtedly the most complicated place to take portraits I have ever known. But, instead of giving up, I decided to take it as an exciting photographic challenge…Read More

Victor Gualda ; The observation of everyday moments

“If a tree in a forest falls and there is nobody to see it and hear it, does it exist?” This Buddhish Koan about observation and knowledge of reality can be extrapolated to photography… Read More

Street Photography by Christine L. Mace

My artwork explores candid moments and unfiltered interactions humanizing the subject, place or space. I capture different cultures and walks of life to document the other and uncover the common thread that ties us together… Read More

Street photography by Andy Kochanowski

I am a street photographer based outside Detroit, USA. My work spans the United States, Europe and Asia, where I shoot un-staged photos. I look to find what I call the indecisive moment…Read More

Street Photography Across Cities

Sidewalk Theatre: Street photography from New York City by Mathias Wasik

There are few cities that inspire the modern world as much as New York City does. It’s ever growing, ever rising – a kaleidoscope of American culture…Read More

This is Spain, Street photography by Seigar

This series is a collection of pop urban photographs taken in Madrid (Aranjuez) and Segovia during short trips in the summer of 2017. It plays with the concepts of identity and nation…Read More

Tomasz Margol ; Street Photography

This is probably the first time in history, such a large-scale project of photographic exhibitions and art, in general, took place in urban space…Read More

London street portraits by Lorenzo Grifantini

The sixties changed the relationship between the city and its inhabitants forever. From the ruins of Victorian austerity and the interminable years of war, arose a “swinging” time that revolutionised the inter-connection between people and their built environment…Read More

One day in Paris by Erlend Mikael Sæverud

Erlend Mikael Sæverud (1975) photographer from Oslo, Norway masters his medium by patiently tapping into solemn moments that elicit universal truths. Known for his black and white photographs with an essence of ephemerality and omnipresence of subtlety, he shifts the narrative by using color in his series One Day in…Read More