In a home on a hill in McArthur, Ohio lives three boys; Robert, Dylan and Jimmy, who are all adopted and now brothers. Their backgrounds are different, but still the same.

They are all the products of parents who couldn’t raise them. In the center stands JC Mullins, a local middle-aged man, who have made it his mission to bring support and caring into the boys’ life. He has adopted them; given them his name and build a home in which they can call their own. The thought of these boys without JC and each other would only contribute to the poor statistics concerning children without parents. Children without love. Children who “Age Out”. But even though they are trying to look ahead, the ghost of their past sometimes shows it’s grim face.

There are 400.000 children in the American foster care system. The majority are placed because of parents abuse and neglect. Around 104.000 children are waiting for adoption. The foster children are having around three different homes, but it’s not unusual that kids are being placed in up to 20 different homes. Later statistics shows that 30% of the homeless people and 25% of the inmates in prison have been in contact with the foster care system.

First stop. McArthur, Ohio. Next. Booneville, Kentucky. Last. Logan, West Virginia. That’s the grand plan for my reportage “ The route of poverty” in the US. I now find myself in the poorest county in Ohio. A week before when I entered the lightened door to Mullin’s Pizza on East Main Street in McArthur I didn’t knew that my original travel would stop and a new would take form.

I notice it right away. JC’s blue eyes shines when my foreign accent tells about my project. He’s behind the counter of his pizzeria which boils in deep fry and Jerry Springer on TV. With flour on his t-shirt and paying customers waiting, his focus concentrates on me and my purpose. It’s like I’m the first stranger in this little town for a long time. Something new. Something exciting. Something else than the usual smell of inbred town-ship, where everybody knows everybody. Where everybody knows too much about everybody. We talk for a few hours and it becomes the beginning of our daily coffee-meetings in the sun in front of his pizzeria. And the beginning of a meeting with one of his sons every day; Josh, Jimmy, Tim, Zak, Rob, Robbie, Robert and Dylan. Each day they show up to either work at the pizzeria or work on a suitable smile with the intention to breed a few dollars from JC, who like a typical parent complains with a loving smile about a lost generation. A youth already retired.

The American Dream

Every morning I sit in front of the pizzeria with a black cup of coffee on the white steel table and enjoy the rays of the November sun in which seems younger than the month. I’ve been in McArthur, Ohio a week. Next to me sits JC in his normal outfit; shorts and a t-shirt, and are blabbering in his own warm and sarcastic way about the mental state of his United States and not the least about Vinton County, where McArthur with it’s 2000 inhabitants are the capital. I look at my watch and are about to leave JC, who enjoys to hear about my daily errands in search of the American Dream or the mere lack of it.

As I place my cup on the table, three young guys around 18 years old walks up to us. JC looks at me. “You have to meet my sons. That’s Dylan, Robert and Jimmy”. As I greet them I see three boys that don’t look like brothers and can’t be due to the fact they are almost at the same age. When I leave the sun and cross the street to get to my Ford Fusion I begin to wonder. Not because I’ve met JCs three sons, but because they are the sons number six, seven and eight I’ve met the last couple of days.

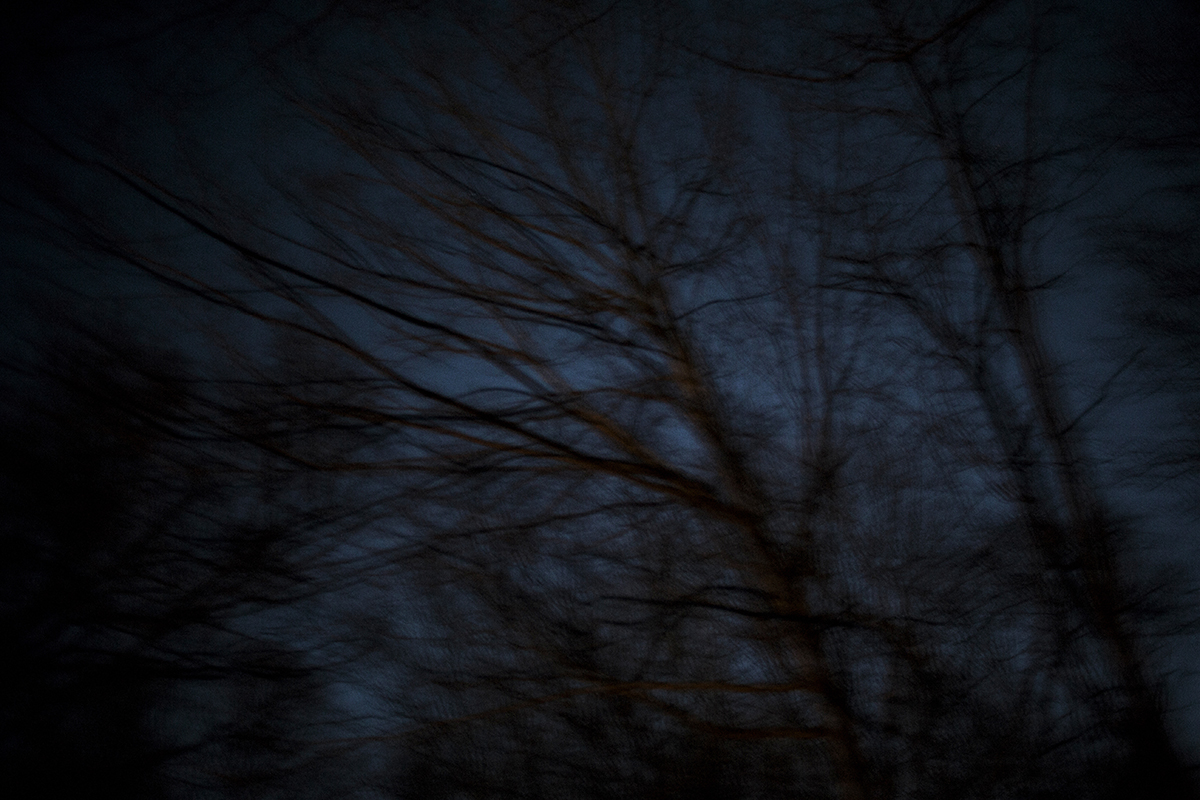

A week earlier I didn’t knew that JC, McArthur or for that matter Zaleski National Park, where the bended roads and naked trees cut of this small town from the rest of Ohio existed. This little town once the place of pioneers fighting their way through the tough foothills of the Appalachians and later found coal and home. Squeezed in between the student town of Athens to the North, the states Kentucky to the south and west, and West Virginia to the east, Vinton County seems forgotten. Until I sat down at Tony’s in Athens and drank a Blue Ribbon. My accent and the camera on the bar disk revealed that I wasn’t from there and my brothers in drink wanted to hear about my quest. They told me about the economically challenged Vinton County where a lot of goodhearted people had lost jobs to a stagnated coal industry. The following morning I drove south. Towards McArthur. Into Coal Country.

I arrived in Ohio to depict poverty. It’s the first time I’m in the US and my senses are constantly bombarded by this giant of a power. Fascination on fascination. All seems so extreme and yet so familiar. Filmic. My upraising in Denmark bears the influence from this country; movies, fast-food, books, cars, videogames and television. All have they visited me in my upbringing. And now they are confirmed. And the language. Of course the language. In third grade when my teacher in a firm voice corrected me. “It’s not called Ain’t”.

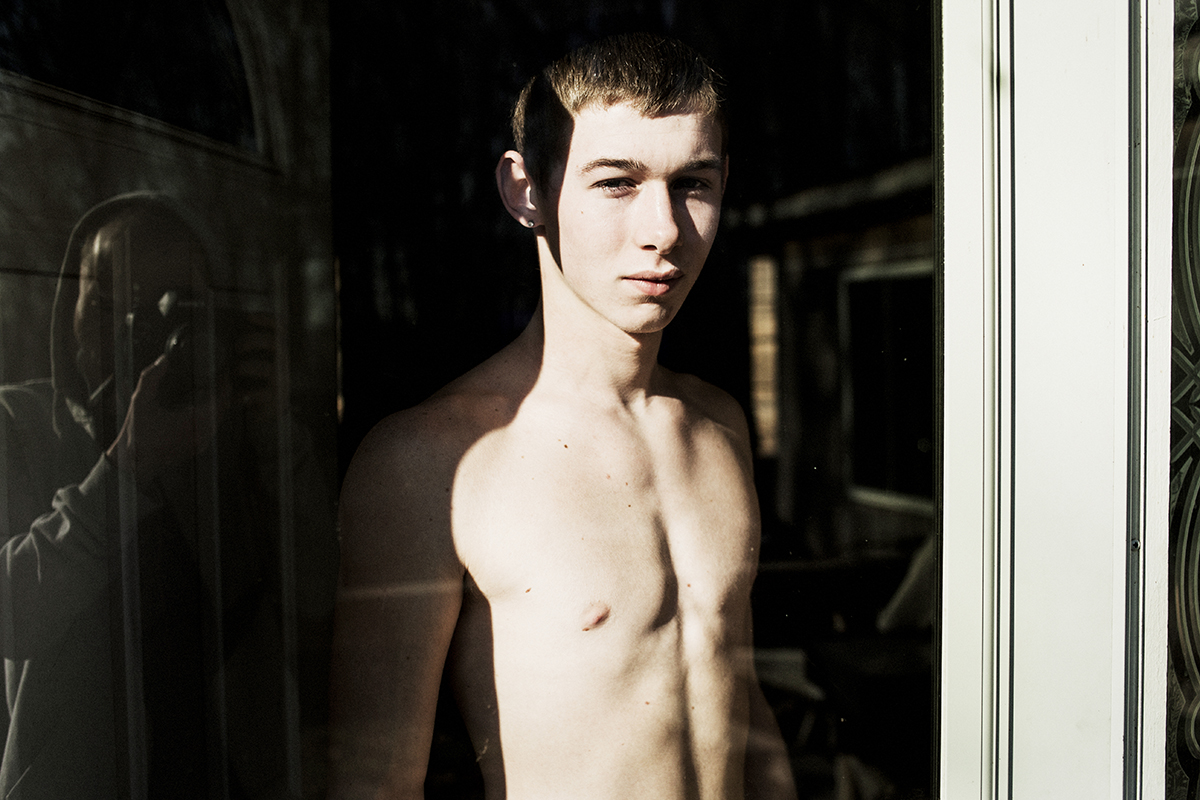

A new name for Robert

”You do know that we aren’t his biological sons, right?”. Robert looks at me. We are in front of the pizzeria and the sun don’t shine today, which explains the empty chair next to me and the coolness of the air. A bit winter like. “I kind of realised that when I met the son number eight”, I respond. “We are adopted”, says Robert. “Actually it’s only me, Dylan and Jimmy who are adopted. JC just call all the boys around him for his sons. But they are all family in some sense”, continues Robert while he drags the last smoke out of his Marlboro. Robert is 18 years old and have just returned form Jackson, a larger town in the neighbouring county. He’s finished high school last year and are now finding himself in a lazy state of searching for a job, which he barely have the energy to apply for. He don’t want to go to college, men at the same time dreaming about becoming a business man. That leads him to disappearing from home months at the time, where he lives with people who wants him until they get tired of him. He’s back because of the latter. The girl he stayed with didn’t want his company anymore. Understandable. He has no money for rent or food, and his ADHD and his many questions makes him energetic in a tiring way. When he don’t have anywhere else to go he always return home. JC adopts him when he is 16 years old. His background are Florida and parents who in their drug abuse becomes violent. He is six years old when he as a foster kid gets in contact with a family. The first time. Later he scrambles from home to home because he is hard to control. Until JC picks him up. And in his stubbornness won’t let Robert go. JC adopts him. Gives him his last name. Mullins.

Too young too early

Vinton County’s tourist office is cross the street from the pizzeria and in the window on a cardboard box a sign says: “38.720 homeless young people in Ohio. Support Sojourners”. Shortly after I find their main office in the outskirts of town and talk to the leaders. Sojourners are an organisation which are helping an increasing amount of foster children with finding a home and caring. Their main focus are on “Out-of-Age”-foster children, who, when they turn 18 years old are being shipped out of the system and are due to support themselves. Each year 30.000 children in the foster care system are “Aged-Out”. And suddenly they ‘re finding themselves without parents, foster parents and or other support. A great deal of them ends up like homeless, criminals or drug abusers. Sojourners have a few apartments scattered around town where they’re helping those young people. I’m making a deal with Sojourners to photograph them and tell their story as a part of my poverty-project.

I’m surprised by JCs reaction. Maybe not surprised, but irritated. A bit angry when he starts to yell loudly when I tell him about my meeting with Sojourners. He doesn’t understand what I want with that organisation, in which the sole purpose is to make money and not do anything good for the children. “They don’t have any heart. No real caring. No commitment”. They are a part of a system that doesn’t work; they don’t have the ability to create caring and loving homes”. He tells me I don’t know anything and I have to admit he is right. I don’t know anything, but that is the most important part of my job as a photo-journalist. Not to know anything. To see and feel and make my own assumptions. My tone a bit sarcastic. My mind floating. My meeting with Sojourners tells me that the last ten years have been an increase in “Out-of-Age”-children in the area.

JC have had a rough day. He seems tired. And maybe that’s why he reacts like he does. He have told me about Jimmy, who at the age of 20 are expecting a child with the 16 year old Shelby. She due to give birth in the coming days. Her family are a wild bunch. Parents who are drug abusers, so are their children. Shelby isn’t like the rest of her family, but the child in her stomach are already the centre of a dispute between JC and the family. The child shall not grow up in a trailer in Charleston, West Virginia, four hours drive from here. At the same time JC worries for Jimmy. Worries about if Jimmy are old enough to be responsible, so JC don’t have to fight the fight alone. Maybe even through yet another adoption. Maybe raise the child. JC creates a lot of problems for JC. Jimmy’s upbringing in the Ghetto of Chilicoethe. His parents on heroin. His 12 siblings, where his older brother are facing 40 years in prison for the murder of his mother-in-law. That’s the background. The fundament for Jimmy before JC makes him of of his own. But the shadows of Jimmy’s mind sometimes blinds the kid. And his lust for marihuana and alcohol seems on the increase. JC seems worried.

There are 400.000 children in the American foster care system. The majority are placed because of parents abuse and neglect. Around 104.000 children are waiting for adoption. The foster children are having around three different homes, but it’s not unusual that kids are being placed in up to 20 different homes. Later statistics shows that 30% of the homeless people and 25% of the inmates in prison have been in contact with the foster care system.

An adoption awaits

Its the last day in McArthur before my planned poverty-tour brings me further into the country. A bit moved I walk the 200 meters form my motel to the pizzeria. I crave coffee, but not the farewell with JC, who over the past ten days have become my friend. So has his real sons, Jimmy, Robert and Dylan. They have become a part of my everyday life In town. We play basketball on the tiresome lanes behind the old high school. We eat together. We make jokes together. We have shared our life and country with one another. JC has opened more up day by day while the coffee have been enjoyed. I know his history. His family history. Their generation by generation in the small town. The first pizzeria they opened. His divorce. And the child who against his will were aborted. His adopted sons. The story about Robert. The story about Jimmy. And the story soon to unfold about Dylan. Dylan isn’t adopted. Yet. Dylan is the youngest of the boys. But his 16 year old age is hiding well behind his old eyes. I assume it’s because of the eight months in prison he spend that have deprived him his childishness. Maybe even earlier. Dylan also grew up in the ghetto of Chilicoethe. With a mother and two siblings. His father was a ghost who only arise on the most wanted posters. Dylan still keeps contact to his family, but they are all separated. His brother on his way to detox in Florida. His mother and sister living together in Columbus, where they sharing the same roof and the same needles. They’re selling themselves for money to get drugs. The cost is pregnancy for his sister. The stories are many.

Thanksgiving

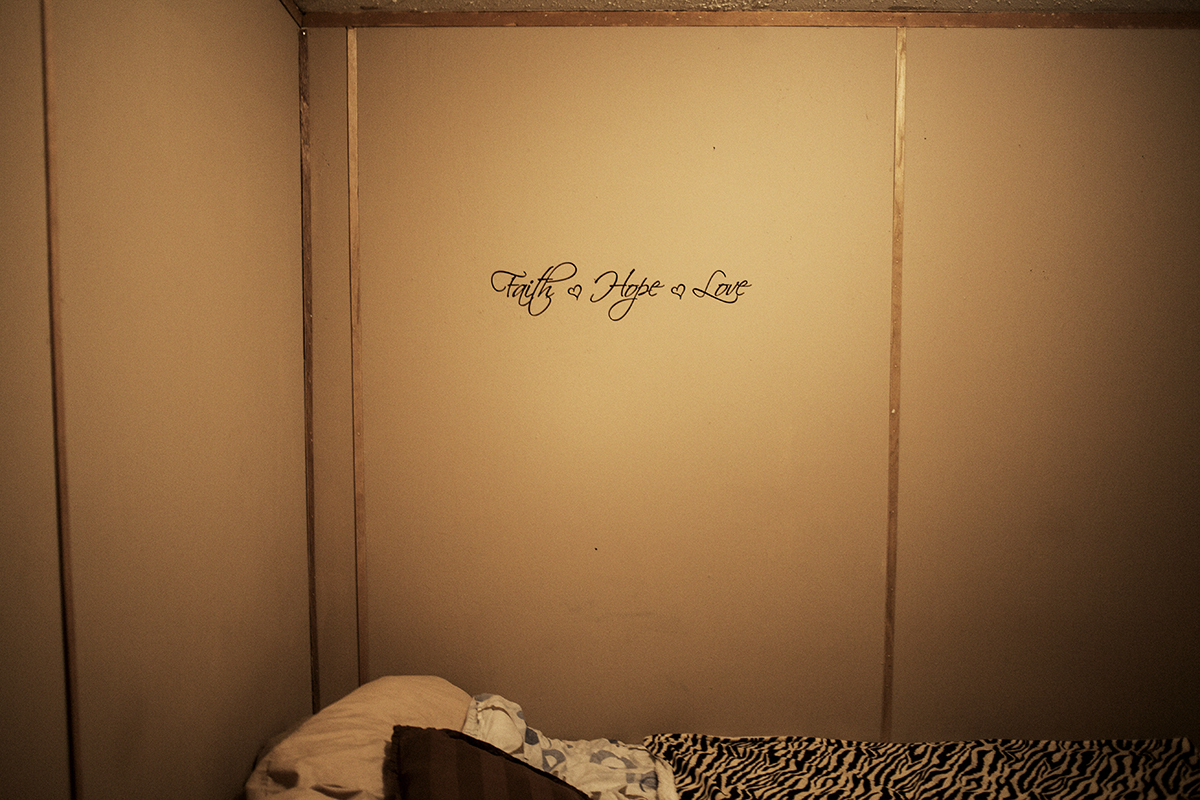

Slightly touched by emotion JC looks at me. “If you want then me and the boys have talked, and we want to invite you for Thanksgiving. You can stay at our home. We have a house on the hill hidden behind the trees. We have a spare room and believe me it’s better than the scrappy Steeles Motel”. The farewell is exactly as expected. Silent and unsaid with the usual “safe trip” and “Hope to you for Thanksgiving”. My gratitude for his kindness, helpfulness and warm heart becomes few words, and his joy for having somebody to talk with, who thinks of other things than food and guns, stays in his eyes. I leave well knowing that I won’t be returning.

The mountains arises as I drive into Kentucky in my search for poverty and destroyed America. McArthur have touched me and the thoughts are circling around the people I have come to know and care for. Late at night after hours on dark roads and colder weather I hit Booneville. I walk into a diner in the small town and asks for a motel. And just then, I realize that I’m starting all over again. New town, new place, new people. It doesn’t make any sense. Poverty? USA? What am I seeking? Poor people? Trashy conditions? Crazy country? Guns? I decide to return to McArthur and move into the house on the hill. To stay with JC and the boys. I decide to document their family. Their home.

A home in which I am about to call my own.

The sound of the aquarium and the trees outside the house are the only company that JC and I are having in the kitchen. We are sitting in the yellowish light around the small table. Its night. The boys are asleep. Properly to the fans with their monotone noise to break the silence and gives them comfort. So should we. Sleep. But we a Miller short from the six-pack we brought from town. JCs beer in the freezer. Mine in the fridge. JC wants his beers icy cold. He doesn’t consume alcohol very often. He use to in his younger days. He rarely keeps alcohol in the house because his cat are very thirsty. That’s how he in a sarcastic way explains that the boys steals the bottles. Its also a way of being the right role model. How is he to explain the boys that alcohol are bad for you if he sits around drinking, We open to last two beers.

I’ve asked JC why he adopts. He could just as well be a foster parent without them becoming family. “Should I just let him disappear into the system? Let him be heavily medicated? And then when he becomes 18, flush him out into society, where he will live on the street as a drug abuser or a criminal?”. He refers to Robert. “Robert have experienced so much neglect in his young life. From his parents as well as from many foster homes. If I want to show the boys that I mean it and will be there for them. If I have to break their patterns I have to invest what I want from them. I show them that they’re a part of me. My sons. My family. In better and worse. I don’t disappear. I’m there”.

Dylan

He was there for Dylan. Everyday. When Dylan sat I court and later in prison. Dylan knew the code to JC’s safe. He knew about the dollar notes behind the steal door. And the gun. Dylan had lived with JC for a year and after a dispute his longing for his mother became unbearable. That was the reason and excuse for the theft. He fleeted to Columbus. He fleeted towards his mother. In rage and at a loss he bought marihuana and booked a room in a dodgy motel at the outskirts of the ghetto. He had never fired a gun before, but felt that it was his ticket through the rough streets to his mothers house. He never came that far. He had just gotten out of the shower when his naked body was forced to the ground by four police officers. JC never show anger. Instead he defended him. And brought him back. Dylan knew everything about being abandoned. For the first time in his life he had somebody who didn’t leave.

The purple pill

JC talks a lot. About a lot. Country and kingdom. The boys and their problems. But rarely about himself. And his voice change emotionally when I ask why he does it. Foster home and adoption. He looks at me and are about to say something, but hesitates. With sincere eyes he utters his words. “Morten, there are something you don’t know”. I look at him and responds. “That’s what you have said all week. I am very well aware that I don’t know anything”. “In 1996 I got the diagnose of leukemia”. I stay silent. “Everything changed. I had been living a rough life with parties and drugs. I had a lot of business’ and everything seemed fine”. The kitchen suddenly seems smaller. The sounds seem gone. “It hit me hard. Everything changed”.

And it changed everything. JC sold of his different business’, but kept the pizzeria which his parents had founded. He didn’t knew if he was to live or die. At the same time the world of his sister trembled in abuse of pills, which left her son, Justin, without a mother or father. JC adopted Justin. The rest is the story about his first encounter with the foster care system; another boy. Then another. And it’s the story about the purple pill which JC has to consume everyday and which are creating the red blood cells his body can’t create. The pill that keeps him alive together with the mission about creating a life and home for his boys. Not just the adopted ones, but their friends as well. He creates a home.

“Morten, I don’t know if I’m alive for another ten years”. The warm atmosphere in the kitchen when we arrived seems gone and concerned eyes meets concerned eyes. “I can’t let them die”, he says and wants the conversation over. “They are children. They are innocent in their parents neglect”.