Belgian photojournalist Alain Schroeder (b. 1955) has been working in the industry for over four decades. First as a sports photographer in the 80s, then shooting book assignments and editorial pieces in art, culture and human stories.

In 2013, he uprooted his life, trading-in his shares in Reporters, to pursue life on the road with a camera. Schroeder now travels the world shooting stories focusing on social issues, people and their environment. «I am not a single shot photographer. I think in series,» he says adding, «I strive to tell a story in 10-15 pictures, capturing the essence of an instant with a sense of light and framing.» He has won many international awards including Nikon Japan, Nikon Belgium, TPOTY, Istanbul Photo, Days Japan, Trieste Photo, PX3, IPA, MIFA, BIFA, PDN, the Fence, Dodho, Lens Culture, Siena, POYI and World Press Photo. [Official Website][Printed Edition][Digital Edition]

Hello Alain, I would like to begin by commending you on such a strong portfolio of work. I have always been fascinated with this as a documentary subject matter and your photographs really do show the brutality of this blood sport. I would like to begin with an open question about your experience documenting these children in the ring. I was curious to know the feelings you felt while documenting these tough situations?

First of all I don’t agree with the words “blood sport”. To me this term is somewhat exaggerated. Muay Thai is an ancient martial art, deeply engrained and respected in Thai culture. It is a fierce fighting style that requires discipline, mental strength and commitment, but it is so much more. Honor, respect, ritual and religious teachings also play a role.

I started my story at a gym owned by a Canadian woman and Thai man. I was impressed by the dedication of all the fighters (girls and boys from 6 to 20 years old) who are eager to adhere to the strict discipline imposed on them. Every day, they run, hit sand bags, do push-ups and abs to strengthen their bodies. They have fun doing it and push themselves to improve.

It requires real commitment given the demanding nature of the sport. And, at the same time they all go to school to get an education. At this gym, they can choose to fight in the ring or just train, and if they want to stop it’s no problem. This is not the case in other gyms run only by locals.

To answer your question about my feelings, during the week of competition in Surin, I was afraid to see bad things happen, but I immediately realized that for the very young fighters (aged 6-10) the referees are extremely attentive and careful. They stop the match as soon as one fighter overtakes another. I did not see any injuries. In fact, the young kids have little technique and not much power. 90% of their hits don’t make contact with their opponent. They are swinging at air.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t endorse these fights. But it seems that the adults do care (at least a little bit) about the health and safety of the kids.

Land and the consequences that many of these children face with regards to health problems, I was wondering if you were ever exposed to such a scenario during shooting? How did you deal with the ‘shock factor’ of having the adults focus on the business side and the children focusing on the fighting side?

I totally respect your opinion but seeing the fights from your home in Europe and seeing them live is completely different. Especially, if like me, you follow them for a few weeks. You become part of their culture and begin to better understand their motivation. For kids from modest backgrounds, Muay Thai offers a chance at a better future for themselves and their families. It’s important to understand the context.

One photograph that really stands out to me is the close-up image of children with numbers written on their chests. It is interesting to me because the photograph is a clear representation of what many people consider to be a form of child labour. Children supporting their families with the necessary funds to live must really take a toll on their mental health and wellbeing as kids.

The numbers on their chests represent their weight. It is clearly written in my caption. A few minutes later an adult will pair them according to their weight and experience. The markings simply represent a convenient way to see their weight at a glance.

While there is a highly passionate debate around kids practicing Muay Thai, and again, I do not endorse these fights, it is important not to make assumptions that may be based on preconceived notions about the sport.

It seems as if these boys all wear a façade that has been forced on them… Were you ever in a situation where a child was being himself or had a genuine conversation with how a fighter was feeling about going into the ring?

From my experience, in Thai culture everybody wears a facade. They avoid confrontation and would never share their true thoughts with a “farang” (foreigner). It would take years to establish the rapport with a young fighter in order to have a genuine conversation. My guess is that some of them would like to stop fighting, but culturally the pressure is too strong.

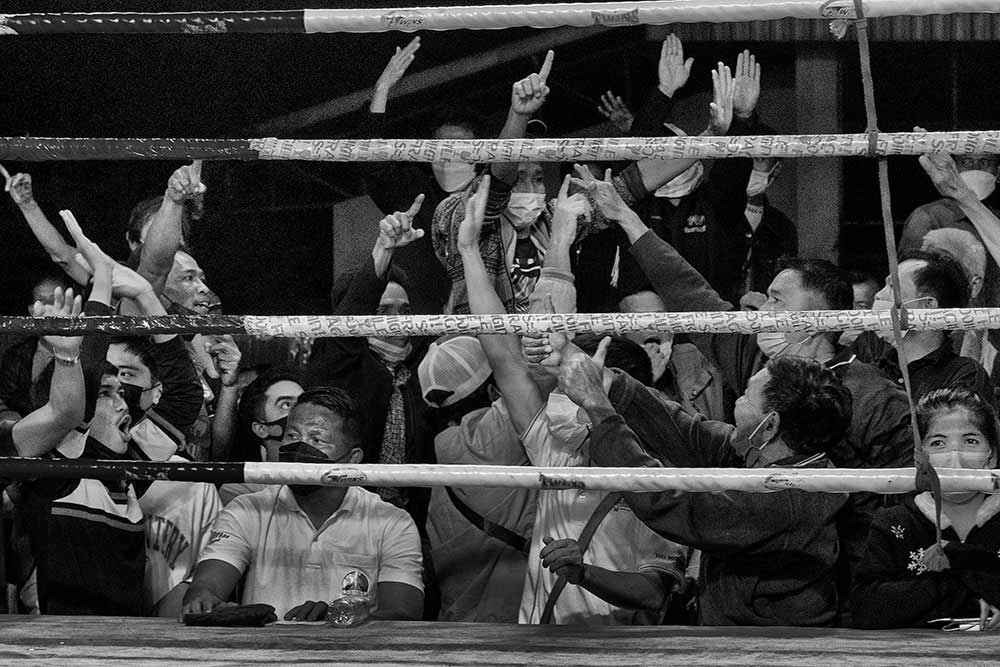

I don’t like the betting aspect of the sport. The money involved puts too much pressure on the kids.

I also agree with the medical staff of Thailand’s Mahidol University who, following a comparison of brain scans of fighters versus non-fighters, concluded that allowing children under the age of 15 to box could lead to various types of brain damage.

Recently, in an effort to calm people down after the death of a teenager, Thai lawmakers proposed another ban on competition for children under 12, but actual legislation has yet to pass. Attitudes are slowly changing, and Thai officials (and other educated people) are beginning to take the health of children into account, but kid boxers do not come from wealthy families. The majority are from poor communities (mainly from the Isan region) where Muay Thai provides vital income, often well beyond what parents can earn. Solving that problem is the first step toward change.

What would you say was the most important part of the whole experience for you? And, if you had to take something positive walking away from this, what would it be?

The positive side is definitely the training part of the sport. I practiced sports (tennis, swimming, football,…) from a very young age (6-7), and I really value the life skills – hard work, discipline, fair play, respect for others – that I learned. Being in a gym and part of a team keeps them away from trouble, drugs, alcohol, prostitution,…

The negative aspect is the potential health risk for the kids. When families are able to support themselves without the help of their children, everyone will benefit.

A hard reality to face is that for many families Muay Thai offers them a better future financially. Were you ever in a situation where you could have discussed this issue with some of the parents who might have been reluctant to let their sons fight?

That is a European perspective. For Thai people, Muay Thai is so engraved in their culture, that very few parents think that way. There is no issue for them, nor the kids, who are proud to help their families. It’s just the normal way of life.

During the competition in Surin all the kids were followed and encouraged by family members. I have seen mothers, fathers and grandparents cheering on the side of the ring; entire families preparing kids for the fights around the ring. For real change, more education in rural areas and less poverty are needed. Regretfully, it may take another generation.

As a final question, I would like to ask you about which photograph you felt was the most compelling out of this whole documentary project? Which image really captures for you the true meaning of this sport of these children?

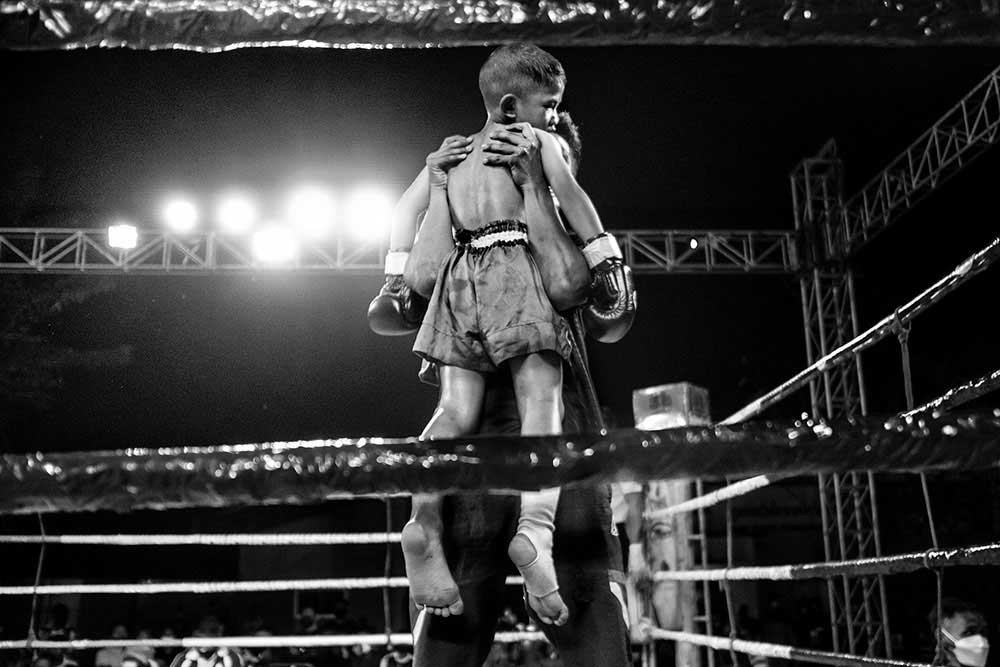

For the last picture of the series, I intentionally put the shot of the kid crying in his corner. The referee immediately saw his distress and stopped the bout. From his facial expression and body language you could tell that he did not want to continue. The issues are obvious; his young age, the lack of protective gear and his freedom to choose to be in the ring. But when thinking about that you also have to understand the Thai point of view that is very different then ours.

I am opposed to children being used for entertainment and financial gain, and the fact that Muay Thai is an ancient Thai sport does not mean it can be practiced without regulation.

Francesco Scalici

A recent MA graduate from the University of Lincoln, Francesco has now focused on landscape photography as the basis of his photographic platform. An author for DODHO magazine, Francesco’s interest in documentary photography has turned to writing and has had various articles, interviews and book reviews published on platforms such as: ‘All About Photo.com’, ‘Float Magazine’ and ‘Life Framer Magazine’. Currently on a photographic internship, Francesco has most recently been involved in the making of a short film titled: ‘No One Else’, directed by Pedro Sanchez Román and produced my Martin Nuza.