Street photography is often described as a way of capturing everyday life in public spaces, but such a definition barely hints at its true significance.

More than a genre defined by subject matter, it is a way of seeing shaped by the complex relationship between the photographer, the city, and the unpredictable dynamics of human behavior.

From its earliest emergence in the modern urban environment to its contemporary global presence, street photography has evolved through the visions of individuals who transformed ordinary moments into enduring visual narratives about society, identity, and perception.

Unlike many photographic traditions that developed within formal institutions or academic frameworks, street photography grew through personal exploration. Its history is not organized around schools or manifestos, but around distinct photographers whose work redefined what it meant to observe public life. Some emphasized compositional precision and the fleeting alignment of form and meaning, while others embraced ambiguity, psychological tension, and subjective interpretation. Together, they created a visual language capable of expressing both the visible rhythms and the invisible structures shaping modern urban existence.

The most influential street photographers did more than document cities; they altered the very understanding of photography as a medium. They demonstrated that the street could function as a space of social revelation, where gestures, encounters, and spatial relationships reveal broader cultural and historical realities. Through their images, everyday scenes became sites of inquiry into power, anonymity, belonging, and the shifting boundaries between public and private experience. Their work also exposed the ethical complexities inherent in photographing strangers, prompting ongoing debates about representation, consent, and the responsibilities of the observer.

As street photography expanded beyond its early geographic centers, it became a global practice reflecting diverse cultural contexts and visual traditions. Photographers from different regions brought new perspectives shaped by local histories, social structures, and aesthetic sensibilities. This global diversification transformed the genre into a pluralistic field where multiple interpretations of public space coexist, challenging the notion that street photography can be reduced to a single style or set of conventions.

To explore famous street photographers, therefore, is not merely to encounter a series of iconic figures, but to trace the evolution of a particular way of understanding the world. Their work reveals how individuals navigate shared environments, how societies express themselves visually, and how the camera continues to mediate our perception of everyday life. Through their contributions, street photography has become not only a record of urban existence, but also a profound reflection on the nature of observation itself.

The Founders Who Defined Street Photography

From Cartier-Bresson to Robert Frank, the first generation transformed everyday urban life into a new visual language based on observation, timing, and human experience.

The history of street photography is inseparable from the individuals who first demonstrated that everyday life in public space could become a subject of profound artistic and cultural significance. Unlike other photographic genres that evolved through formal institutions or academic traditions, street photography emerged largely through the intuitive practices of a small number of pioneering figures whose approaches reshaped how the camera could engage with the urban world. These photographers did not merely document the street; they defined the visual and conceptual foundations upon which the genre continues to rest.

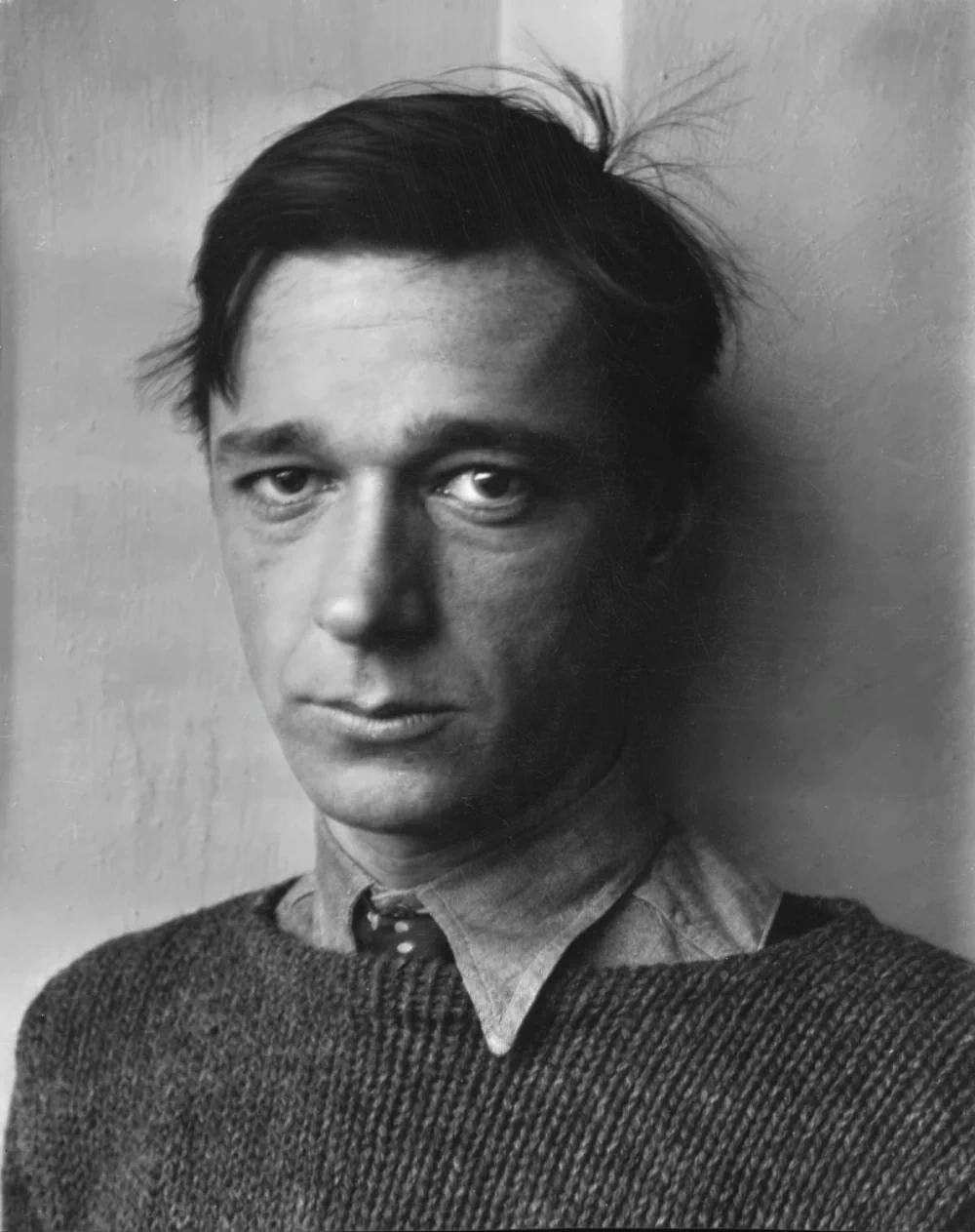

Among these foundational figures, Henri Cartier-Bresson occupies a singular position. His contribution extended far beyond the creation of iconic images. He established a philosophy of photographic observation rooted in the belief that meaning could be captured within fleeting instants of visual alignment. His concept of the “decisive moment” articulated a new way of understanding the relationship between time, perception, and composition. For Cartier-Bresson, the street was not simply a physical environment but a dynamic field of human interaction in which gestures, movements, and spatial relationships converged unpredictably. His work demonstrated that the ephemeral rhythms of urban life could be rendered with extraordinary precision, transforming transient encounters into enduring visual statements.

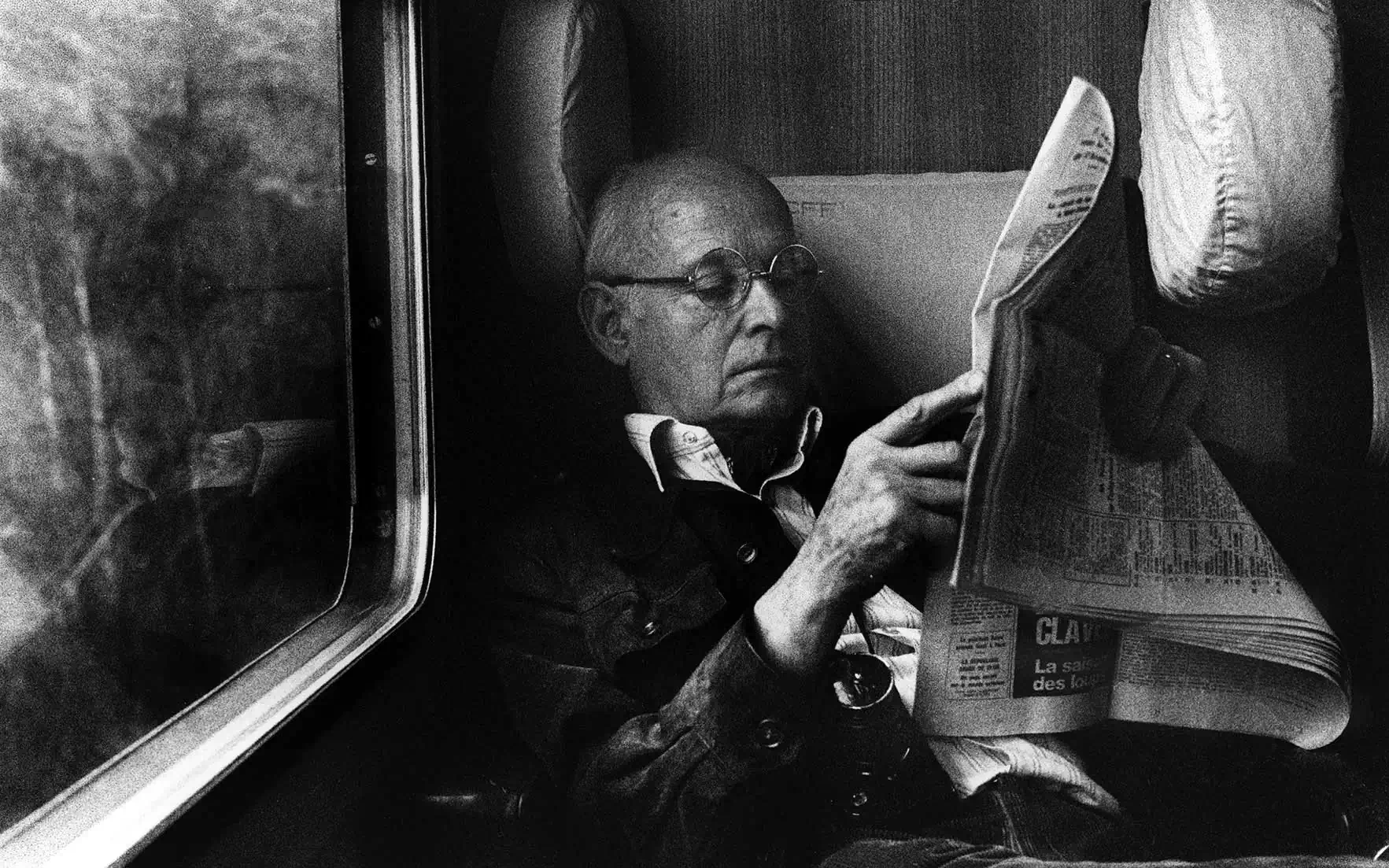

Equally important was the role of Walker Evans, whose approach introduced a different dimension to early street photography. Whereas Cartier-Bresson emphasized intuitive timing and compositional harmony, Evans focused on the quiet psychological presence of individuals within modern urban environments. His candid subway portraits, made with concealed equipment, revealed a profound attentiveness to the inner lives of anonymous subjects. These images conveyed a sense of introspection and emotional distance that contrasted sharply with the more dynamic humanist narratives prevalent in European street photography. Evans’s work underscored the potential of the street photograph to function not only as a record of external behavior but as a reflection of interior states shaped by the pressures of modern urban existence.

The work of Robert Frank marked a decisive turning point in the development of street photography. His photographic journey across the United States during the 1950s culminated in The Americans, a body of work that fundamentally challenged prevailing assumptions about both photography and national identity. Frank rejected the aesthetic clarity and compositional balance that had dominated earlier street photography. Instead, he embraced a visual language characterized by irregular framing, high contrast, and emotional ambiguity. His photographs revealed a fragmented society marked by inequality, isolation, and subtle tensions often overlooked in official representations of American life. Through this approach, Frank expanded the expressive range of street photography, demonstrating that it could serve as a powerful instrument for social observation and critique.

Together, these foundational photographers established the essential parameters of the genre. They defined the street as a site of unpredictable human encounters, emphasized the importance of spontaneity and mobility in photographic practice, and demonstrated that ordinary moments could carry profound symbolic and emotional significance. Their work also revealed that street photography is not bound to a singular aesthetic formula. Even at its inception, the genre encompassed multiple approaches ranging from formal precision to psychological introspection and social critique.

The legacy of this foundational generation extends far beyond their individual images. They transformed the camera into a tool for exploring the complexities of modern public life and established a visual vocabulary that continues to influence contemporary practitioners. By redefining how photographers engage with urban environments, they laid the groundwork for the subsequent evolution of street photography as a dynamic and continually expanding field of artistic expression.

The Rebels Who Transformed the Genre

Photographers like Winogrand, Moriyama, Maier, and Meyerowitz broke traditional rules, introducing ambiguity, subjectivity, and new visual approaches to the street.

If the first generation of street photographers established the visual foundations of the genre, the following wave of practitioners fundamentally reshaped its direction by questioning its assumptions, expanding its expressive range, and introducing radically different ways of engaging with public space. These photographers did not simply refine the existing language of street photography; they destabilized it. Their work marked a shift from harmony toward ambiguity, from observation toward personal interpretation, and from the search for visual order toward an embrace of urban complexity.

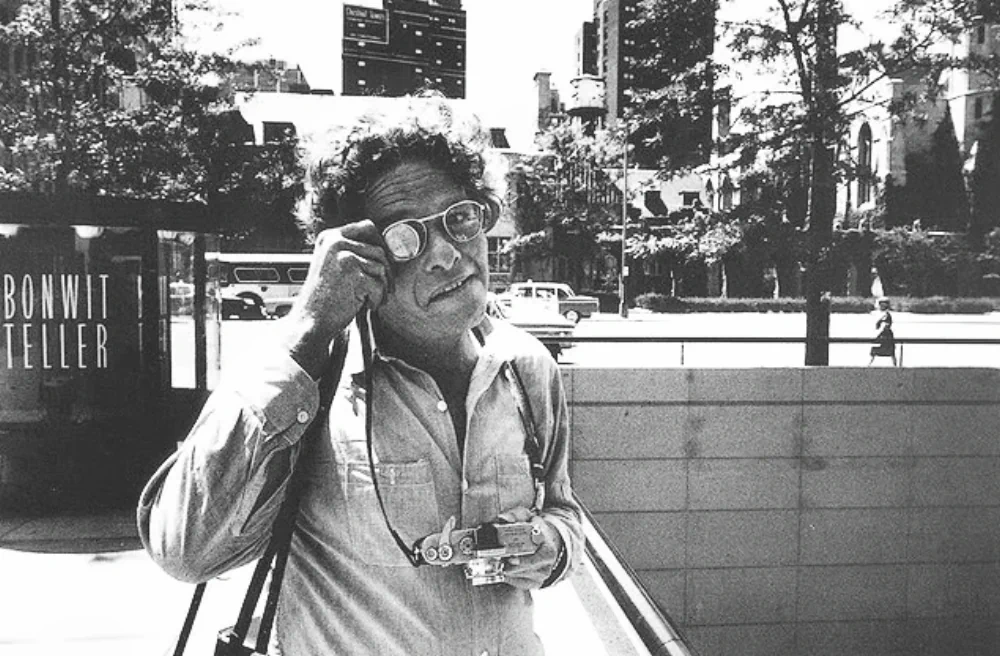

Among the most influential figures in this transformation was Garry Winogrand, whose approach represented a decisive break from the compositional ideals associated with earlier practitioners. Rather than waiting for moments of visual balance, Winogrand immersed himself in the unpredictable flow of urban life, photographing relentlessly as a way of exploring how reality changed when filtered through the camera. His images often appear disordered, filled with overlapping figures, tilted horizons, and gestures that resist clear interpretation. Yet this apparent chaos reflects a deliberate attempt to capture the disorienting rhythms of modern cities. Winogrand’s work demonstrated that street photography did not need to resolve visual or emotional tensions; it could instead reveal them.

While Winogrand explored the instability of urban experience in the United States, Daido Moriyama developed a radically different but equally transformative vision in Japan. Emerging from the turbulent social and cultural landscape of postwar Tokyo, Moriyama rejected the notion that street photography should strive for clarity or compositional refinement. His photographs are characterized by extreme contrast, heavy grain, and blurred motion, creating an aesthetic of fragmentation that mirrors the psychological dislocation of rapidly modernizing urban environments. For Moriyama, the street was not a coherent social stage but a sensory overload of images, signs, and fleeting encounters. His work redefined the genre by emphasizing perception itself as a subjective and unstable process.

The transformation of street photography during this period also included a profound revaluation of authorship and visibility, exemplified by the work of Vivian Maier. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Maier worked outside institutional frameworks and exhibited little interest in public recognition during her lifetime. Yet her extensive archive revealed a sustained and deeply attentive engagement with urban life. Her photographs often capture subtle emotional exchanges, moments of vulnerability, and complex interpersonal dynamics unfolding within ordinary environments. Maier’s work demonstrated that street photography could operate as an intensely personal practice, shaped by long-term observation rather than by immediate publication or external validation.

Another crucial figure in this expansion of the genre was Joel Meyerowitz, whose contributions helped legitimize the use of color in street photography. For decades, black and white had dominated the field, associated with its modernist aesthetic and documentary heritage. Meyerowitz challenged this convention by exploring how color could convey the sensory richness and psychological atmosphere of urban spaces. His photographs revealed how light, hue, and spatial relationships interact to shape the emotional experience of the street. By integrating color as a central expressive element, he broadened the visual possibilities of the genre and influenced subsequent generations of photographers.

What unites these diverse figures is not a shared style but a shared willingness to redefine the boundaries of street photography. Each challenged prevailing assumptions about how reality should be represented, emphasizing that the genre is not governed by fixed rules but evolves through continuous experimentation. Their work shifted the focus from capturing isolated moments of visual harmony to exploring the complexities of perception, memory, and social interaction within rapidly changing urban environments.

The influence of this generation extends beyond specific aesthetic innovations. They transformed the very conception of what street photography could be. It was no longer understood solely as an act of observation rooted in humanist ideals. Instead, it became a flexible and multifaceted practice capable of accommodating subjective vision, emotional ambiguity, and diverse cultural contexts. This expansion set the stage for the contemporary global landscape of street photography, in which multiple voices and perspectives coexist within an ever-evolving visual dialogue.