His fixer, Dagmidmaa, met him and a few ragtag travellers he had joined en route from Beijing on the platform as the Trans Siberian train pulled into Ulaanbaatar station.

It was 1992, at the start of his photography career.

Whatever success the body of work he later produced from that trip achieved began with Dagmidmaa, a twenty seven year old mother of one who shepherded him across the country with skill and diligence.

Having long been fascinated by Mongolia’s isolation and the centuries old lifestyle of its nomads, he had been inspired to travel there after reading an illuminating feature article in The New Yorker the previous year. As a country emerging from seven decades of communism, it was a challenging time for locals, who were grappling with a new economic model. Regardless of the hardships, the picture painted by the writer of this new frontier drew him in with stories from the road.

He had based himself in Tokyo the previous year after turning his back on a promising, though potentially stifling, future as an architect and was determined to pursue life as an independent magazine photographer.

Just before leaving Tokyo, he had been given the contact of a local fixer by a photographer who had recently returned from Mongolia on assignment. Slender and tall in conservative denim jeans and a knitted cardigan, her dark bob neatly cut, Dagmidmaa had a caring disposition and an affability that served her well. Having studied English at Teachers Training College, and with the country at a critical political and financial crossroads, she recognised an opportunity to strike out on her own and assert her independence from her husband. She was setting herself up as an interpreter and fixer for tourists and business travellers, and he was among her first clients.

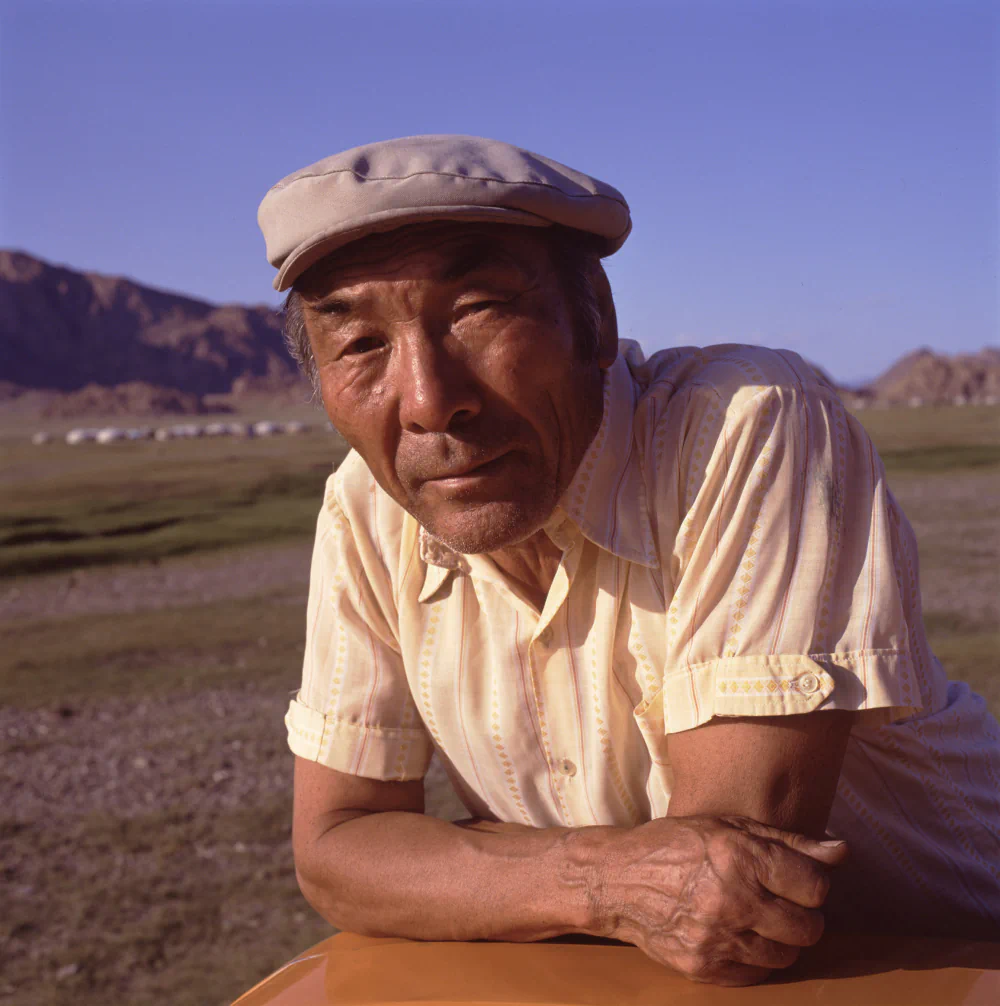

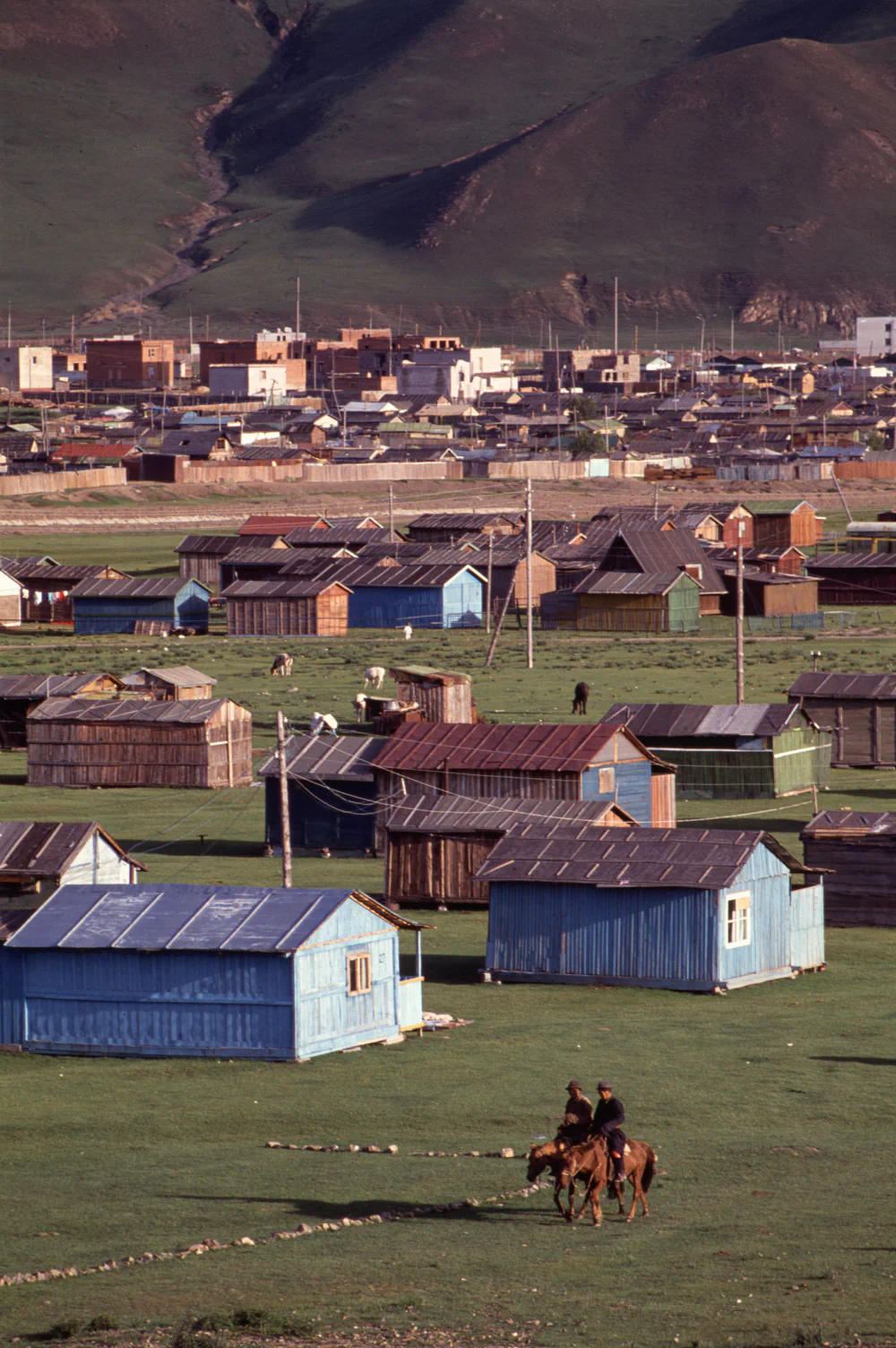

During the month he spent in Mongolia, he lived with Dagmidmaa’s mother for the first week in her Soviet era apartment block in suburban Ulaanbaatar. At the time, with many nomadic herders relocating from rural areas to urban centres in search of work, the city’s population was swelling. On occasion, he roamed with Dagmidmaa on the outskirts of town, where nomadic families lived in makeshift housing using their traditional gers as homes. The effects of Mongolia’s transition to a free market economy were palpable. Supermarket shelves were mostly barren, and drunken men often loitered in the city’s squares in search of work or trouble. Barely a day passed without him being cursed or threatened because local men assumed he was Russian, whom they were quick to blame for their troubles. It was only through the calming intervention of Dagmidmaa, or her brother in law who sometimes accompanied them, that confrontations were avoided.

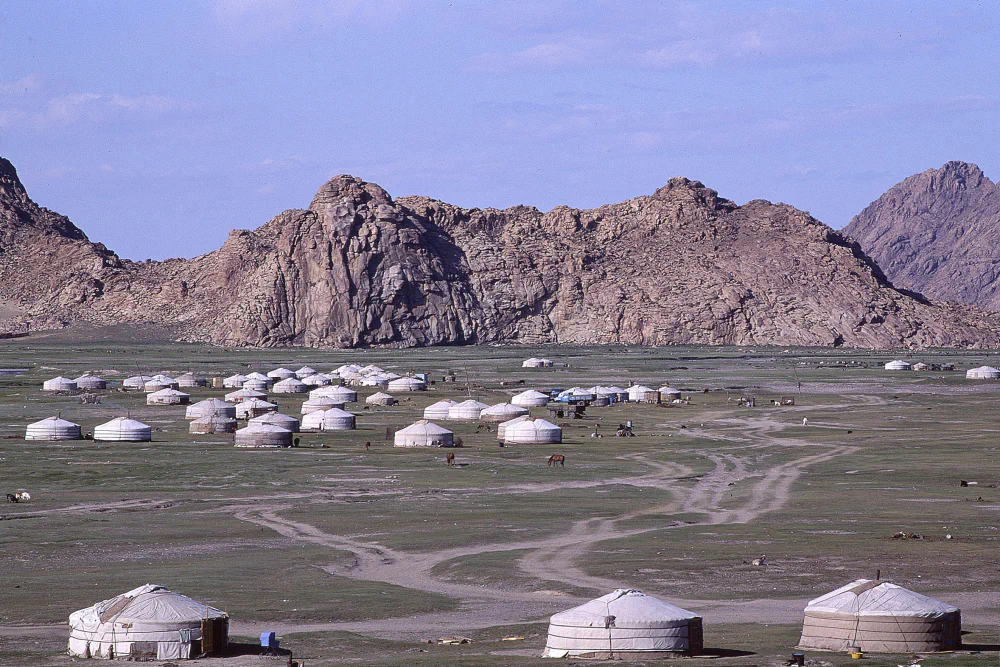

To gain a sense of life far from anywhere, he wanted to travel to the Altai Mountains in the far west near the Kazakhstan border. Dagmidmaa had heard that domestic flights were resuming after a six week hiatus, as the government had secured additional aviation fuel bought on credit from Russia.

At the office of the local airline, MIAT, crowds pressed at the counter, desperate for tickets. After he pulled his passport from his shoulder bag to give to Dagmidmaa, pushing and shoving broke out as people jostled for attention. He later realised that the commotion had been orchestrated by a group of thieves who had seen him reach into his bag and used the diversion to pickpocket his money belt. By the time he noticed, tickets in hand, it was too late. They had taken 2,500 USD in cash, the equivalent of twenty or more years’ salary. He had been advised to carry small denominations in what was largely a cash economy, resulting in a bulky bundle that he had kept in his bag.

A dismayed Dagmidmaa reported the theft at the downtown police station. Although sceptical, she accompanied him. The duty officer led them into an interview room to file a report and produced old grey files listing known criminals, each with a black and white mugshot glued to the pages. The scene felt like something from a 1940s film noir, with cigarette smoke drifting through the room, and he realised there was little chance of recovering the money. Nonetheless, they still had tickets to fly to Hovd, a frontier town in the shadow of the Altai Mountains.

As rough and tumble as Mongolia appeared, the hospitality he experienced with Dagmidmaa’s family and among nomadic households remained unforgettable. With her as his fixer, day trips were arranged from Ulaanbaatar so he could photograph, while she negotiated with drivers to use their private vehicles. They also organised longer journeys to stay with nomads and a visit to the Gobi Desert, on which she unexpectedly brought her four year old daughter, Duvreemaa. He interpreted this as a sign of marital instability. During that trip, the Russian vehicle they were using broke down, leaving them stranded overnight while the driver and his companion walked to a distant ger for help.

With Dagmidmaa, doors opened. They were always welcomed with tea, cheese, cured meats, or airag, fermented mare’s milk, and were often offered a place to sleep.

Before leaving Mongolia, he photographed members of Dagmidmaa’s family, including her daughter, her mother Dolgor, her siblings and their partners, and Moobaatar, a sad eyed young family friend who was staying with Dagmidmaa’s mother while grieving the recent death of his wife.

After returning to Beijing, he began experiencing intense sugar cravings. A few days later in Hong Kong, he developed pain in his liver after drinking whiskey and cola. By the time he returned to Tokyo, his energy levels had collapsed and he was hospitalised with hepatitis, later convalescing in Australia for several months. The work from Mongolia remained untouched during that time.

The following year, once settled again in Tokyo, he attempted to contact his former fixer. Mongolia’s postal system commonly used workplace addresses as mailing points, as individual residential addresses were not formally recognised. The Cyrillic address he possessed belonged to Dagmidmaa’s sister in law, a nurse at a hospital. Despite repeated attempts, he never received a reply, and the portraits he had hoped to send to the family were never shared.

A few years ago, he sought help to find Dagmidmaa. In the more than thirty years since his journey, Ulaanbaatar had undergone immense change, fuelled by international mining deals. Her mother’s old apartment was eventually located, though it was occupied by someone else. Neighbours remembered her mother, who had long since died, but knew nothing of the other family members. There was mention of one married sister living elsewhere, but the trail ended there.

Of all his travels, this one continues to endure for a single reason. He still does not know what became of Dagmidmaa.

About Philip Gostelow

I am a portrait and documentary photographer and filmmaker. Throughout my career, I have been based in Tokyo, Shanghai, Sydney, and Perth, working with clients such as Time, Figaro, The Wall Street Journal, Vogue China, and The Weekend Australian Magazine. My photo collage work was featured at the Noorderlicht Photo Festival in 1999, and my series Black Christmas Bushfires (2001) is held in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Australia and the Museum of Australian Photography.

My book Visible, Now The Fragility of Childhood was published as an e book by Democratic Books in 2006. In Australia, I have been a finalist for both the Bowness Prize and the Head On Portrait Award. I have directed several films, including Max Pam The Freddie Incident, which was shortlisted for the Western Australian Screen Culture Awards in 2023. I graduated in Architecture from Curtin University in 1984, and I am married with two children. [Official Website]