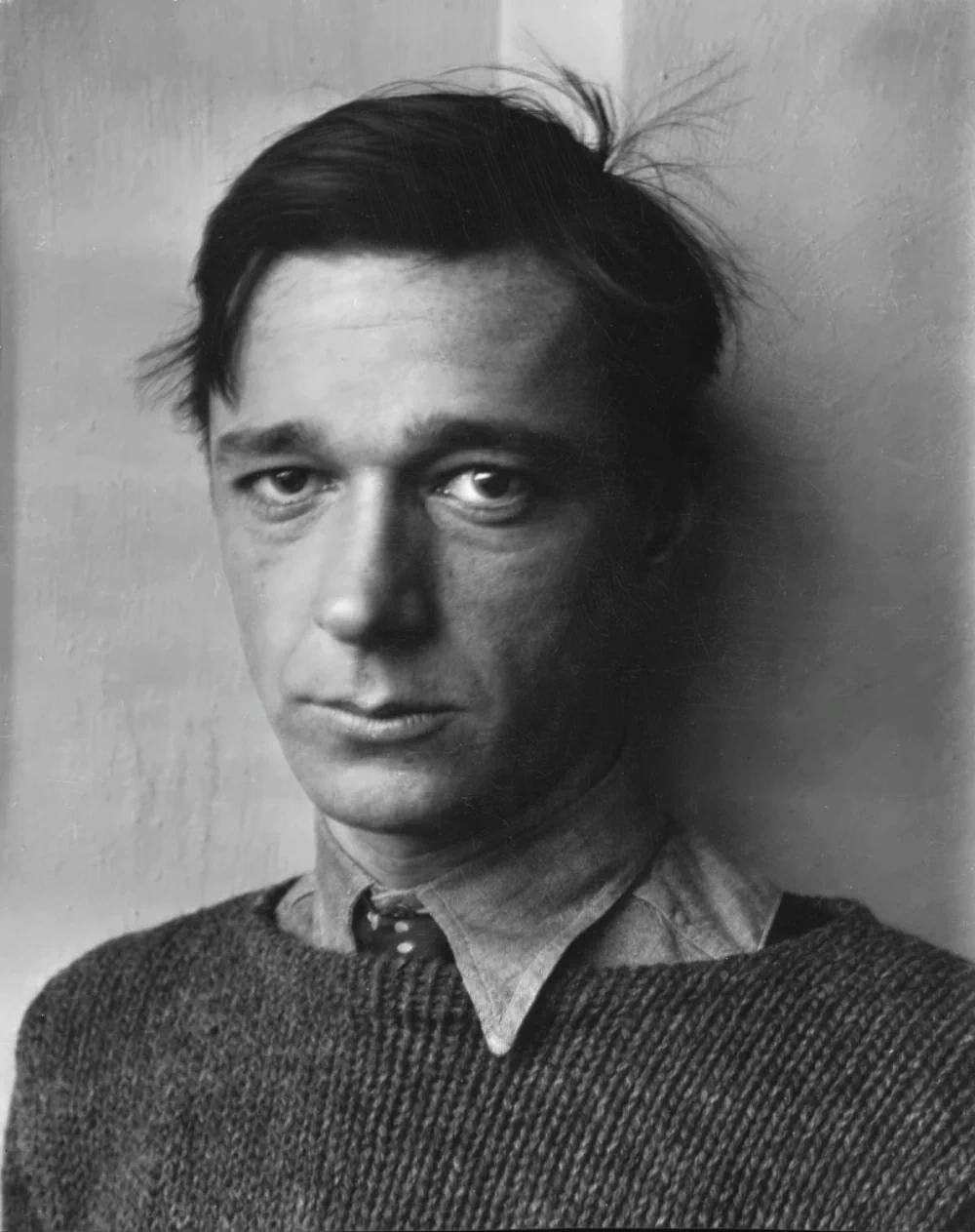

Walker Evans occupies a singular position in the history of photography. Not because of spectacle or emotional intensity, but because of restraint. His work is built on distance, on a deliberate refusal to intervene, dramatize, or sentimentalize what stands before him.

At a time when documentary photography was often driven by explicit empathy, moral persuasion, and emotional impact, Evans chose another path: to look, to record, and to step back. That choice, still debated today, raises one of photography’s most complex ethical questions: what does it mean to look without intervening?

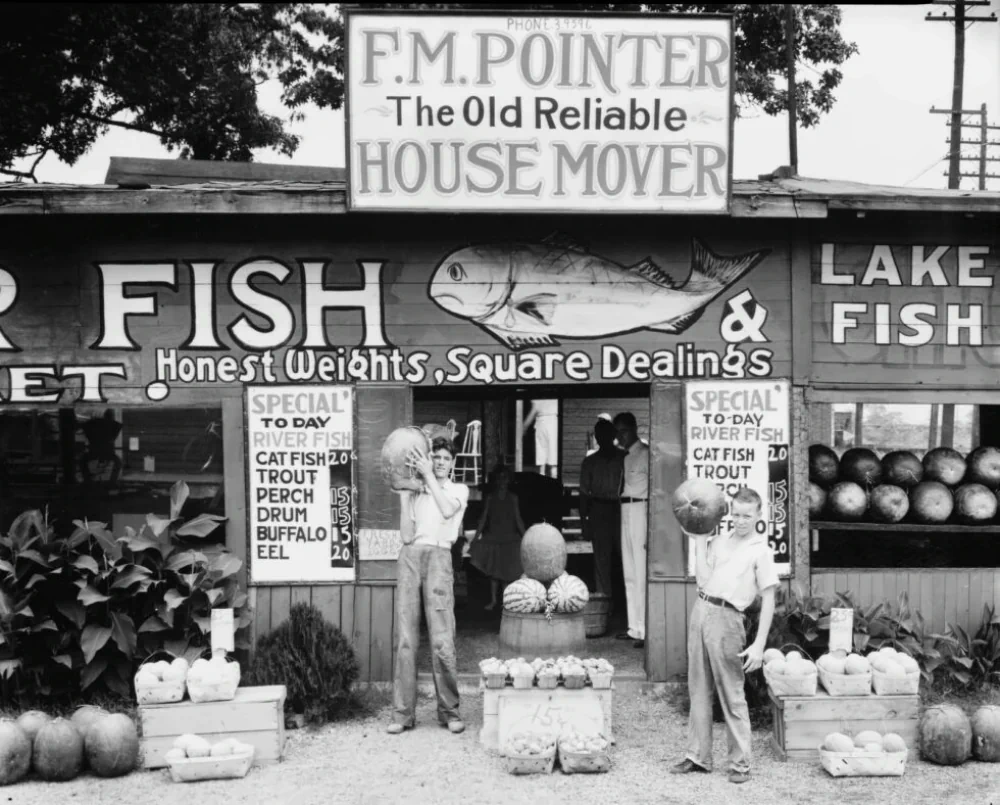

During the 1930s, in the midst of the Great Depression, documentary photography in the United States assumed a clearly social function. The work of the Farm Security Administration sought to make rural poverty visible, raise public awareness, and justify state intervention policies. In this context, the camera was understood as a tool of denunciation. The photographer was not only an observer, but a moral mediator between the suffering of others and the collective conscience.

Walker Evans took part in this project, but never fully aligned himself with its logic. While other photographers sought to move viewers emotionally, Evans insisted on a frontal, dry, seemingly neutral gaze. His portraits of farmers, his facades, his interiors lack explicit gestures of compassion. There are no emotional underlines, no dramatization. What remains is a precise, almost obstinate description of what is there.

This stance has been interpreted in opposing ways. For some, Evans represents a rigorous ethics of respect: not appropriating the suffering of others, not manipulating it to provoke an emotional response. For others, his distance borders on coldness, even indifference. Can a photograph be ethical if it limits itself to observing without intervening? Is it enough to look with rigor when the context seems to demand action?

Evans defended the idea that photography should aspire to a form of objectivity, even while knowing that such objectivity can never be absolute. His well-known notion of a “documentary style” did not refer to the absence of style, but to its containment. The photographer should minimize his visible footprint in order to allow the subject to exist on its own. It was not about disappearing, but about not imposing oneself.

In his portraits, especially those made with James Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, this ethic becomes particularly evident. Faces look directly at the camera with a mixture of firmness and vulnerability, but without dramatics. There are no tears, no theatrical gestures. Evans asks nothing of his subjects beyond their presence. And he offers nothing in return, at least on the visible plane of the image.

Here a central tension emerges. Looking without intervening can be understood as a form of respect, but also as a form of power. The photographer observes, records, and leaves. The camera fixes a reality that will continue its course regardless of the image produced. The ethical question does not disappear simply because the scene has not been manipulated.

Evans was fully aware of this ambiguity. That is why he rejected sentimentalism. He believed that explicit emotion could become a form of exploitation. Showing pain directly, he thought, does not guarantee understanding, only emotional consumption. His wager was different: to trust the intelligence of the viewer, their capacity to read the image without being led by the hand.

This trust is itself an ethical position. Evans did not seek to dictate a moral response, but to create a space for observation. His images do not tell us what to think or how to feel. They present a presence that demands to be confronted without excessive mediation. In this sense, his work stands in direct opposition to the contemporary logic of images designed to provoke immediate reaction.

However, this ethic of distance is not without problems. Absolute neutrality does not exist. Choosing not to intervene is also a form of intervention. Deciding where to stand, what to frame, when to press the shutter and when not to always involves taking a position. Evans knew this, but preferred to assume the contradiction rather than conceal it beneath a layer of visual humanism.

In contemporary photography, this question remains fully relevant. In a world saturated with images of suffering, constant intervention has led to an emotional inflation that ultimately empties images of meaning. Compassion becomes automatic, predictable, almost decorative. Against this backdrop, Evans’s distance takes on renewed relevance.

Looking without intervening does not mean looking without responsibility. It means accepting that photography cannot always, and should not always, resolve what it shows. That its function is not necessarily to save, but to make visible. Evans understood the camera as a tool of cultural record rather than an instrument of redemption.

This places him closer to an anthropological tradition than to an activist one. His images function as documents of an era, but also as extremely conscious formal constructions. Evans’s ethics cannot be separated from his aesthetics. The frontal gaze, the absence of gesture, the strict composition are all part of the same decision: not to interfere more than necessary.

Today, when intervention has become the norm, when photographers often present themselves as protagonists, mediators, and judges, Evans’s work feels uncomfortable. It forces us to ask whether every image must position itself explicitly, whether every photograph must take sides in a visible way, whether ethics can be measured only by declared intention.

The ethics of looking without intervening is not a universal solution. It cannot be mechanically applied to all contexts. But it does introduce a necessary doubt: to what extent is intervention a form of control? To what extent is the insistence on emotion a way of directing the viewer and limiting interpretation?

Walker Evans offers no closed answers. His legacy is not a formula, but a tension. An invitation to think of photography not as a heroic act, but as an exercise in silent responsibility. Looking without intervening is not withdrawing from the world, but accepting that the gaze itself has consequences, even when it chooses not to act.

In a visual culture obsessed with urgency, Evans’s position reminds us that sometimes ethics are not found in doing more, but in knowing where to stop. That distance, when understood properly, can be a form of respect. And that looking, when done with rigor and awareness, is already a form of commitment.