For decades, the idea has been repeated that Robert Frank “broke the rules” of photography. That his work was a kind of rebellious act, a conscious rupture with tradition, a frontal rejection of what was considered good photography in his time.

It is a convenient, almost mythological reading, but a deeply inaccurate one. Robert Frank was not a photographer acting from ignorance of the rules, nor from an impulsive rejection of technique. He was someone who understood the photographic language so deeply that he knew exactly which rules could be ignored without the image collapsing.

That distinction is crucial. Ignoring a rule is not the same as being unaware of it. Frank did not work from clumsiness or carelessness. He worked from a radical clarity about what he wanted to say and about the limits of photography as an expressive tool. His gesture was not destructive, but selective. He did not blow up the system; he passed through it.

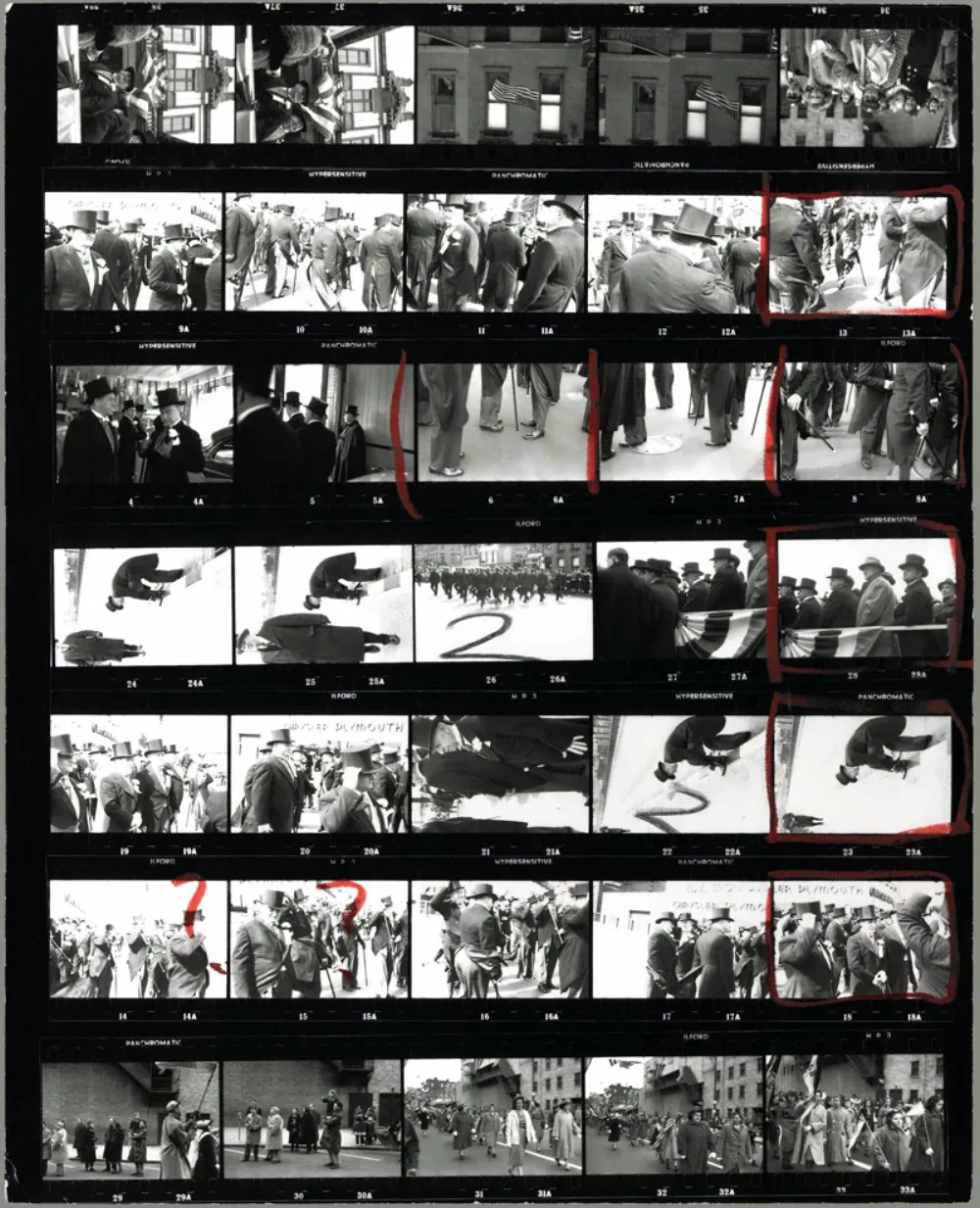

When The Americans was first published in the late nineteen fifties, the reaction was as virulent as it was revealing. Frank was accused of being technically poor, formally incorrect, even unpatriotic. The photographs were too dark, badly framed, out of focus, tilted. The content seemed fragmented, uncomfortable, lacking a heroic narrative. But what truly disturbed critics was not the form, but the gaze. Frank was unwilling to beautify what he photographed or to offer a reassuring version of American reality.

At the time, dominant documentary photography was still deeply tied to the idea of clarity, order, and legibility. Images were expected to explain, to organize the world into something understandable. Frank did exactly the opposite. He accepted ambiguity, silence, unresolved tension. He was not trying to describe the United States; he was trying to feel it. And for that, many rules were simply useless. His apparent formal carelessness was, in fact, a conscious strategy. The imperfect framing, the tilted horizon, the visible grain were not mistakes, but decisions. They were the most honest visual way to convey a fragmented, contradictory, deeply human experience. Frank understood that formal perfection could become a barrier between the image and the emotional truth he wanted to transmit.

What was truly radical about Frank was not his aesthetic, but his position. He deliberately placed himself outside the center. As a Swiss immigrant, as an external observer, he looked at the United States without the need to confirm it or celebrate it. That distance allowed him to see fractures that dominant narratives preferred to ignore: racial segregation, loneliness, latent violence, the banality of consumption, the weight of national symbols emptied of meaning.

Frank did not reject photographic tradition. He absorbed it. He knew Walker Evans, understood the legacy of the Farm Security Administration, respected classical documentary photography. But he also knew that this language was no longer sufficient to explain the world in front of him. Photography needed to become more subjective, more open, more vulnerable. It needed to accept that not everything could be explained with clarity.

In this sense, Frank was less a revolutionary than a translator. A translator of a modern experience marked by fragmentation, speed, and alienation. His photography does not seek to close meanings, but to open them. It does not offer answers; it proposes sensations. And to achieve this, he had to ignore certain rules that belonged to an earlier visual context. This attitude remains deeply relevant today. Innovation is still often confused with gratuitous rupture. “Incorrect” images are celebrated without a real understanding of why they are so. Frank’s legacy is not in blur or tilted framing, but in the radical honesty of his gaze. To copy the form without understanding the intention is to empty his work of meaning.

Robert Frank reminds us that the rules of photography are not natural laws. They are cultural, historical, contextual agreements. They are useful as long as they help say something. When they stop doing so, they become noise. The true creative act is not to break them systematically, but to know when they are no longer useful.

That is why his work remains uncomfortable. Not because it is formally transgressive, but because it resists domestication. It offers neither comfort nor closed narratives. It demands active involvement from the viewer, a slow reading, an acceptance of discomfort.

Frank understood something fundamental: photography does not need to be correct to be truthful. It needs to be honest. And that honesty sometimes requires disobedience. Not out of rebellion, but out of coherence. At a time when photography is once again trapped between aesthetic formulas, algorithms, and market expectations, Robert Frank’s lesson feels especially relevant. It is not about breaking the rules to attract attention. It is about knowing them well enough to understand which ones can be ignored without betraying what the image is trying to say. That is the truly radical gesture. And that is why Robert Frank did not break the rules: he understood which ones to ignore.