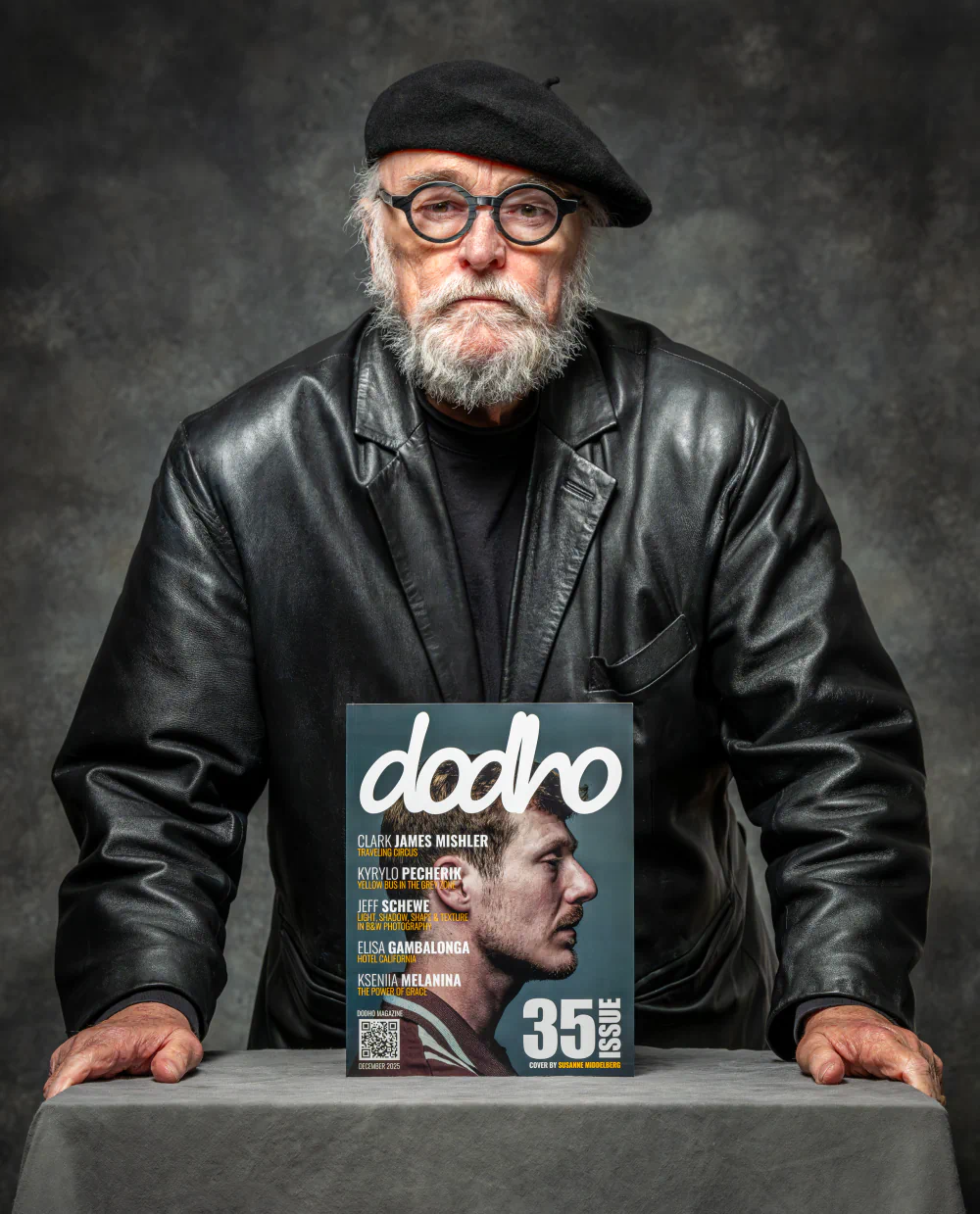

Jeff Schewe is one of the featured authors in Issue 35 of Dodho Magazine.

His work is articulated through a deep relationship between thought, experience, and form, where photography operates as a language that goes beyond the visual to become a way of analyzing and understanding the world.

In this interview, we talk with him about the moment when the image became a form of thought, the motivations that continue to activate his practice after decades of work, and the constant tension between intuition, technique, and contemplation. [Official Website] [Issue #35]

At what point did the image begin to become a habitual way of thinking rather than just a visual practice? What led you to remain within photography and not other languages?

I’m not sure the “image” has ever really become a habitual way of thinking. I think the image evolves from my visual practice. I certainly have lots of habits—some good, some bad—but I don’t really like to rely on habit as a way of working because habits imply a degree of repetitive action rather than creative innovation. I really like trying new things and often try to break bad habits.

As far as sticking with photography and not trying other creative “languages,” I don’t think I have remained completely locked into only photography. I have written several books about digital imaging and photography. I’ve also used my skill set in sculpture and 3D design to augment my photography. I’m always on the lookout for new ways of creative expression.

After so many decades of work, what still sparks your interest enough to begin a new project? How would you describe your relationship with photography today?

New projects tend to create themselves from my “playtime,” meaning I tend to play with creating images, and projects seem to evolve from that time. Playtime is an essential aspect of creativity and has been something I’ve practiced since early in my photographic career. I also try to expand my photographic reach by trying new techniques and different genres of work. I find complacency to be the enemy of creativity. I like engaging in activities that make my palms sweat—doing things I don’t know how to do but want to learn. Doing new things can be scary—hence the sweaty palms—but I’ve learned to enjoy the experience rather than fear it.

My relationship with photography today is like a marriage. There are ups and downs in any relationship, and it’s a constant struggle to maintain it. But like any marriage, the basis is built on love. I love photography (most of the time), and I work hard to keep the marriage healthy. Of course, there are times when the marriage hits a snag or encounters rough periods, but I just have to power through those times. I’ve actually been married for a bit over 52 years—about as long as I’ve been a photographer—so I have a lot of practice in keeping a relationship intact. I think of myself as an old shark: I’ve been around a long time, but if I don’t keep swimming forward, I’ll die. I’m not ready for that.

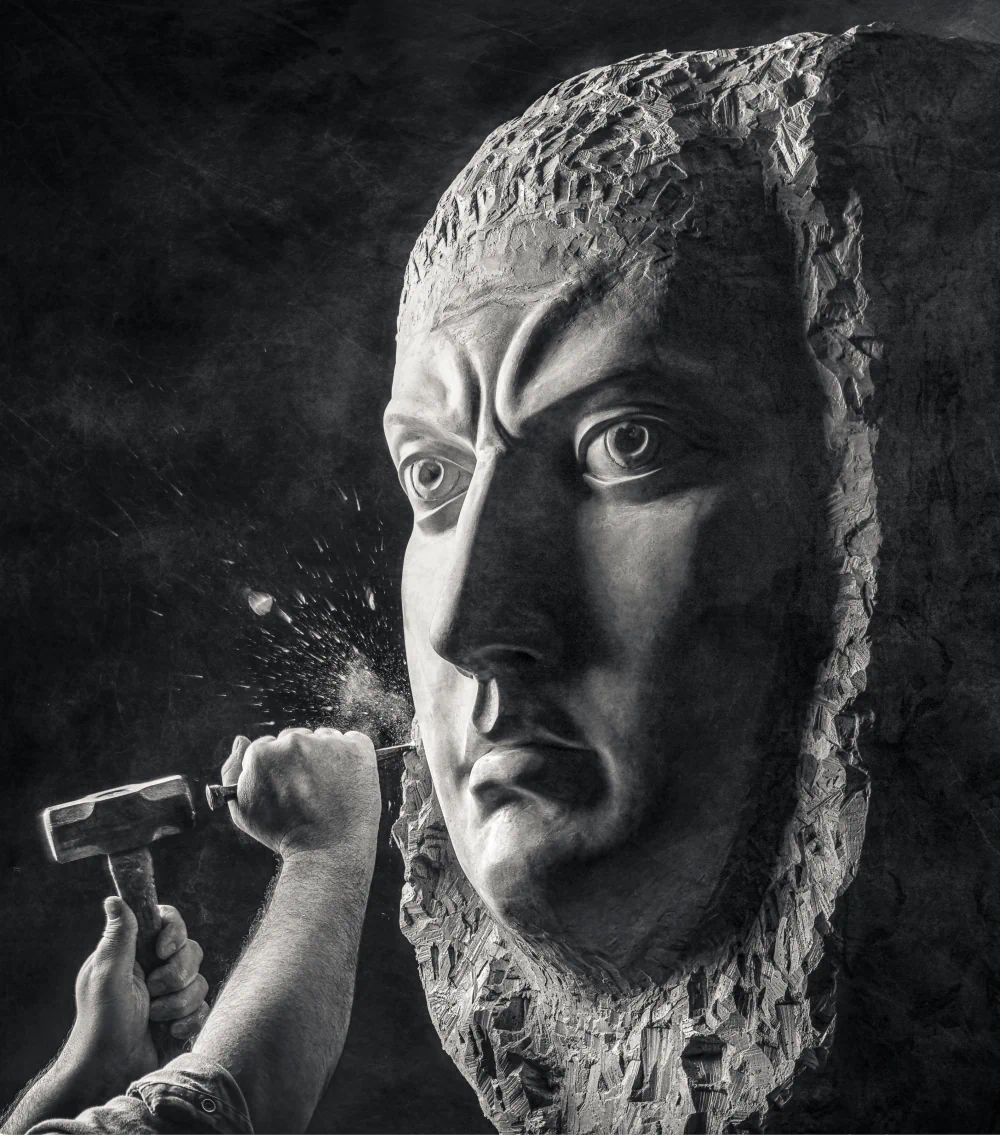

In Light, Shadow, Shape & Texture, what idea or concern was at the origin of the work, beyond its formal appearance?

That body of work comes from a resurgence of what got me hooked on photography in the first place: black and white. I still remember the first few times I went into the darkroom to print; it was an overwhelming experience that shaped my craft and my love for photography.

Black-and-white photography is all about light, shadow, shape, and texture on the print. Of course, I no longer need to deal with smelly chemicals now (and I really don’t miss that), but I will sit at the computer for hours on end, not unlike the hours I used to spend in the darkroom. The difference now is that I can see and work on my photographs with an immediacy that makes the old days in the darkroom seem primitive. I also feel that my craft has evolved and advanced. The power and control one has over photographs in digital imaging apps far exceed the limited control available in the darkroom.

And while some may disagree, I see my digital photographic pigment prints meeting—if not exceeding—the dynamic range and depth of chemical prints. Combined with the cornucopia of papers and printing media available today, it’s truly the golden age of photographic printing, which is sad because so many people don’t print anymore.

From what position do you place yourself as an author when you photograph: closer to analysis, intuition, or contemplation? What did you discover about the project during the editing process?

I would turn that around and say my position is analysis based on contemplation, with a healthy dose of intuition. I’ve been making photographs for so long that most of the time I don’t really think about what I’m doing; I just click the shutter. Of course, I work to put myself in position to be somewhere, doing something, with my camera at hand. There are times when I’ll look at a scene and analyze the options and opportunities, but at some point, after contemplating, my trigger finger gets itchy and wants to click the shutter, you know? I often don’t actually realize exactly when my finger twitches and the shutter clicks. I think that’s my intuition taking over.

Were there images that reflected something unexpected back to you about your own way of seeing? How did you know the project had reached a point of closure?

I’m often surprised during my selection and editing process. I go through pretty quickly and look for the obvious successful photographs. However, I often find that photographs that aren’t so obvious at first glance end up being the strongest and most successful. When I’m out shooting, my head is on a swivel, looking to find what I can and visualizing what something will look like when processed. Depending on the circumstances, I may make shots that don’t have much chance of succeeding as a learning experience. A mentor and teacher I admire, Sam Abell, calls it “practice shooting.” The light might not be right, the scene might not be clear, or I may not have the right equipment to be successful, but I’ll take the shot anyway to see what I can learn. And sometimes those photographs work well in spite of the lowered expectations at the moment they were captured.

As far as learning when a project has reached a point of closure, I don’t know. I don’t think any of my projects have arrived at that point yet. I’m always keen to add to a body of work. I’m still adding to bodies of work I started 30 to 40 years ago.

I have many separate collections, often drawn from past work, that I call upon for exhibition calls for entry. Dodho is a good example. After assembling this body of work over the last few years, I was reinvigorated by working with color. When Dodho announced the call for the COLORS book, I went through many different bodies of work, picking out the strongest color photographs for submission. I was, of course, very grateful and humbled that my photograph Globe Hands was selected as the first-place image. That photograph was made just over 30 years ago. My bodies of work seem to age well, and I keep adding new photographs each year.

What conditions does a body of work need in order to grow with you over time? What do you want to remain from a series once it is finished?

The conditions needed for growth over time seem to fall into set categories: timelessness and classic themes combined with elegance and, often, simplicity. Another requirement is that the body of work must continue to interest me—compel me, if not demand, that I keep at it. And another important criterion is that I must enjoy doing the work. It has to be engaging and enjoyable. I’m too old to do stuff that isn’t fun anymore. At this stage of my career, I’m fortunate that I don’t have to do anything I don’t want to do. So I do what I love and what I want.

As for what I want to remain from a series once it’s finished—well, nothing is ever finished. You get that, right?

Your technical knowledge is extensive. Which technical decisions are conscious from the outset, and which emerge in response to the image? How do those decisions shape the final result?

In recent years, the technology of photography has altered the way I work. The trick is to keep learning and growing. Having the advantage of knowing how a photographic image can be controlled in post-processing, and having the skill set to render the final image, gives me great confidence.

When I’m working on a photograph on the computer, I find myself developing a relationship with it. I see the areas that need attention and make the adjustments and changes the image wants me to make. I listen with my eyes to what the image wants from me. As for how those decisions shape the final result, it’s an evolutionary process. Once I’ve chosen a photographic image to invest my time in processing, it doesn’t matter how long it takes or how much effort it requires—I’m committed.

How has your criterion for judging your own work evolved over the years?

I’ve made a concerted effort to engage in the fine art photography field after retiring from active commercial advertising photography. How I judge my own work has evolved due to the various portfolio reviews I’ve received, exhibitions and shows I’ve entered, and most notably the workshops I’ve taken in recent years.

I’ve taken workshops with Duane Michals, Jay Maisel, Elizabeth Opalenik, Keron Psillas, Sam Abell, Arthur Meyerson, Keith Carter, Greg Gorman, and Peter Turnley. I’ve learned valuable lessons from each of these fine teachers. I credit them with expanding my understanding of the art and craft of photography, as well as fostering the love I have for the work I do. I now look at my work through a more sophisticated and practiced eye.

Don’t get me wrong. I take feedback and reactions from others with a grain of salt. I consider what others may say, but ultimately, I am the final judge and jury of my own work.

When a project comes to an end, what drives you to begin another? How do you distinguish today between superficial curiosity and a real need to work through an idea?

I think I’ve already covered the fact that my projects seem to be never-ending, but I will admit to often beginning new bodies of work, often as a result of assembling collections to submit to exhibitions.

I use Adobe Lightroom to manage my archive of photographic images. I can’t tell you how many actual collections I have, but there are many. I create a new collection for every body of work I produce and every exhibition I enter. I build these collections from a vast archive of digital images, many originating from film scans and, more recently, digital captures. I’m somewhat embarrassed by the sheer number, but you must understand—I’m a packrat. I never like to throw things out. So when I scroll through my well-organized archive, I can always go back and find material to build a new body of work.

Building a new body of work also involves creating new photographs to add to and augment what I’ve already made. That’s the joy of photography. I have many ideas, and I crave producing new work from them.

By the way, if you’re curious, I have over 800,000 photographs in my Lightroom catalog.

What visual or conceptual territories do you feel are still open for you, even without a defined form?

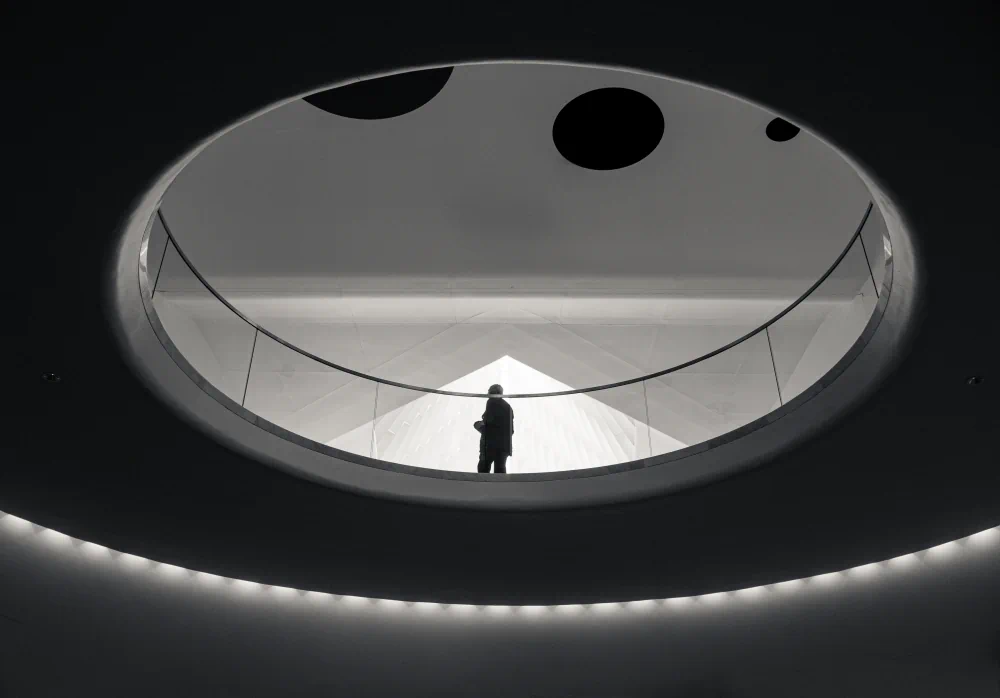

00My practice encompasses a wide range of subjects, unified by a consistent pursuit of strong visual narratives and unique, often unusual perspectives. I am equally interested in the subtle resonance of the familiar and the striking unfamiliarity of new environments. Whether at home or abroad, in the field or in the studio, I seek moments that demand attention and carry visual weight. For me, the camera is both a tool of exploration and a means of expression.

At its core, my work is about seeing. Each image is an act of recognition—an acknowledgment of the significance hidden in fleeting moments. My goal is not simply to document, but to connect: to share my way of seeing and to remind viewers that beauty, complexity, and depth can be found in both the extraordinary and the everyday.

I see photographs everywhere I look.