Few photographers have exercised control as absolute and as unsettling as Irving Penn. His images appear calm, restrained, impeccably composed.

Nothing seems to shout. Nothing appears overtly aggressive. And yet, beneath that surface of order and elegance, Penn’s work exerts a form of pressure that is difficult to ignore. The violence in his photographs is not physical, not theatrical, not explicit. It is silent, structural, and deeply psychological. It resides, above all, in the neutrality of the background.

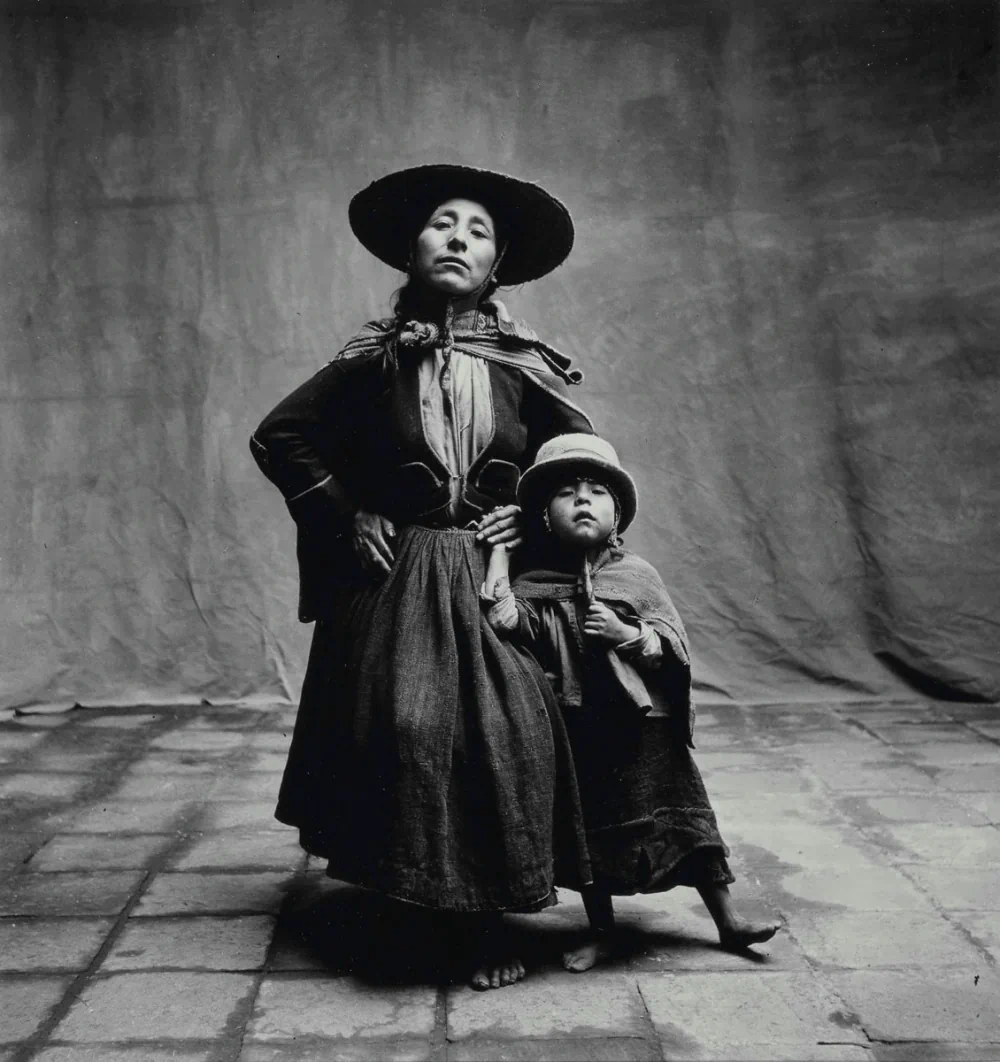

The neutral background is often described as a device of clarity. A way to isolate the subject, remove distractions, focus attention. In Penn’s hands, however, neutrality is never innocent. The blank background does not liberate the subject; it exposes it. It does not protect; it interrogates. Penn’s backgrounds function less as spaces and more as conditions. They create an environment where nothing escapes scrutiny and where every gesture, every wrinkle, every hesitation becomes visible.

Penn understood something fundamental: emptiness is never empty. A neutral background is not the absence of context; it is the imposition of a context so absolute that it leaves no room for escape. His seamless backdrops, corners, and flat planes operate like controlled chambers. Once inside, the subject has nowhere to hide. There is no narrative to lean on, no environment to soften the encounter. The photograph becomes a confrontation between the viewer and the photographed, mediated only by Penn’s ruthless precision.

This is why Penn’s portraits often feel unsettling even when they are elegant. The silence is oppressive. The subject stands alone, stripped of anecdote, stripped of protection. Clothing becomes armor. Posture becomes defense. Expression becomes evidence. The background does not decorate; it accuses.

Unlike documentary photographers who situate their subjects within social or geographic frameworks, Penn removes the world entirely. What remains is not purity, but exposure. The subject is reduced to presence. And presence, when isolated, becomes vulnerable. The neutral background acts like a spotlight without light, a void that magnifies rather than erases. This strategy reaches its most literal form in Penn’s corner portraits, where subjects are placed between two converging walls. These images are often discussed in terms of formal brilliance, but their psychological charge is far more important. The corner is not just a compositional device; it is a trap. The body is compressed. Space closes in. The subject cannot expand outward; it must fold inward. The background becomes architecture of constraint.

What makes this violence silent is Penn’s refusal to dramatize it. There is no chaos, no visible force. Everything is controlled, polite, almost classical. The aggression lies in the refusal of comfort. Penn does not offer empathy through environment. He does not soften the encounter with visual cues. The subject is seen as they are, or at least as they perform themselves under pressure.

This pressure produces extraordinary results. Penn’s sitters are alert. Even when they appear relaxed, there is tension. A slight stiffness in the shoulders. A guarded gaze. A posture held a second too long. These are not candid moments; they are negotiated moments. The photograph records not just how someone looks, but how they endure being looked at.

The neutral background amplifies power dynamics. Penn holds the power, and he does not pretend otherwise. The studio is his territory. The rules are his. The background enforces those rules. It eliminates excuses. If the subject appears uncomfortable, the discomfort cannot be blamed on circumstance. It belongs to the encounter itself. This is particularly evident in Penn’s portraits of artists, writers, workers, and cultural figures. Stripped of their environments, they cannot perform their social roles. A butcher, a painter, a poet—all are reduced to bodies, faces, stances. Their identity is no longer narrated by tools or surroundings. It must emerge through presence alone. The background demands truth, or at least a convincing performance of it.

Fashion photography, in Penn’s work, undergoes the same transformation. Clothing is no longer contextualized by lifestyle or fantasy. Dresses and suits stand against emptiness. The model becomes sculptural. The garment becomes an object under examination. Desire is not generated through narrative, but through precision. The background refuses seduction and, paradoxically, intensifies it.

Penn’s still lifes reveal the same logic. Objects placed against neutral grounds lose their function and gain weight. A cigarette butt, a bone, a piece of trash becomes monumental. The background isolates the object until it can no longer be ignored. This is not aestheticization; it is confrontation. The viewer is forced to look longer than is comfortable.

The silent violence of Penn’s backgrounds also extends to time. By removing temporal markers, the images resist historical placement. The subject exists in an eternal present. There is no “before” or “after” implied. This timelessness intensifies the pressure. The photograph becomes definitive. There is no suggestion of change, no escape into narrative progression. The subject is fixed.

This is why Penn’s work continues to feel contemporary. The neutrality of his backgrounds aligns disturbingly well with modern systems of visibility: surveillance, profiling, classification. The blank background resembles institutional spaces, identity photos, clinical environments. The subject is isolated to be examined. Penn’s elegance does not soften this; it sharpens it.

Yet, to reduce Penn’s work to cruelty would be simplistic. The violence is not sadistic. It is analytical. Penn is not interested in humiliating his subjects, but in revealing the structure of representation itself. The neutral background exposes how much we rely on context to construct meaning. When that context is removed, identity becomes unstable. The photograph reveals not who someone is, but how fragile that idea is. nThis fragility is what makes Penn’s work profound. The background does not erase humanity; it tests it. Some subjects resist. Some comply. Some collapse inward. All are transformed. The photograph becomes a record of that transformation.

In a photographic culture obsessed with authenticity, Penn’s work is a reminder that authenticity is not given; it is produced under conditions. The neutral background is one such condition. It is not passive. It acts. It exerts force. It shapes behavior. It reveals power.

To look at an Irving Penn photograph is to witness a controlled experiment. Remove context. Apply pressure. Observe the result. The violence lies in the method, not the outcome. And because it is silent, it lingers. It follows the viewer. It unsettles long after the image has been absorbed. Penn did not photograph neutrality. He weaponized it. And in doing so, he revealed something uncomfortable: that clarity, when absolute, can be as aggressive as chaos. That silence can be louder than noise. And that the most severe forms of violence in photography often arrive disguised as elegance.