To speak of Brassaï is to speak of the night. Not as a mere setting, nor as a time slot associated with mystery, but as a visual territory governed by its own rules.

For Brassaï, the night was not a dark extension of the day, but an autonomous world that demanded a different way of seeing, walking, and photographing. In that deep understanding lies one of his most significant contributions to the history of photography.

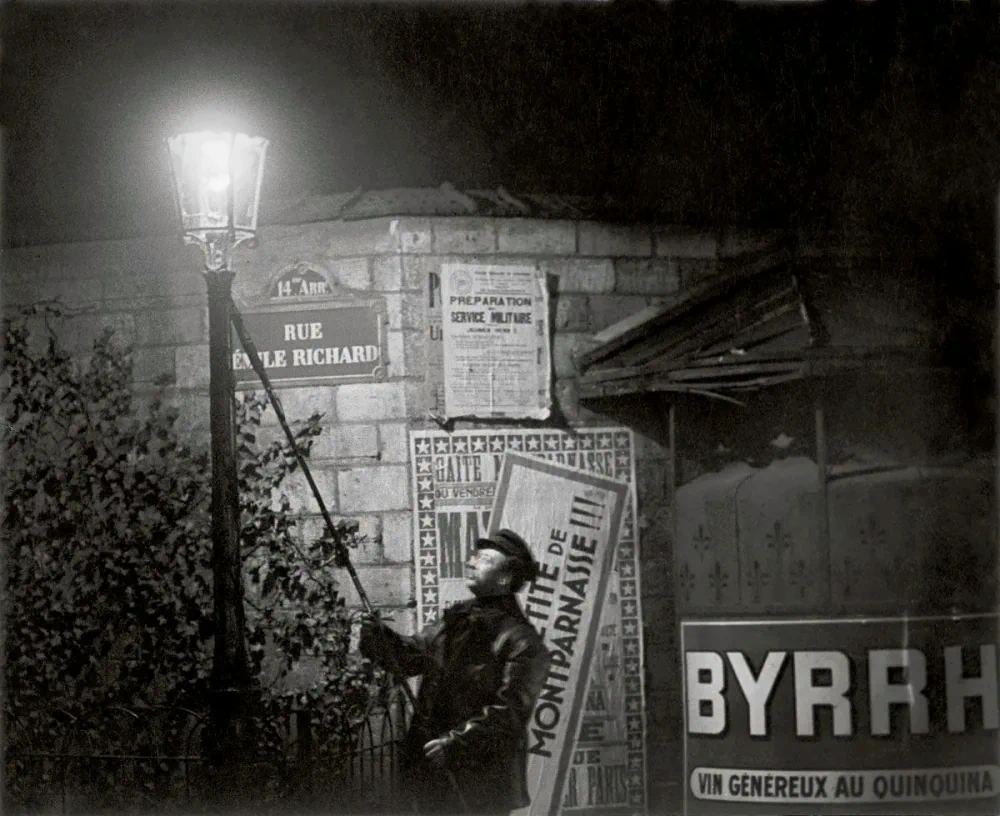

When Brassaï began roaming Paris at night in the 1930s, the city radically changed its face. The streets emptied or became populated by different bodies, different rhythms, and different rules. Artificial light, scarce and uneven, distorted volumes, stretched shadows, and transformed the ordinary into something strange. Many photographers avoided this territory, considering it technically hostile. Brassaï, on the contrary, embraced it as a language in itself.

Photographing at night at that time was no trivial gesture. Film emulsions were slow, exposure times long, and the margin for error enormous. But Brassaï did not try to overcome these limitations; he integrated them. Blur, fog, grain, and harsh contrast were not flaws to be corrected, but expressive elements that defined the visual grammar of the night. Technique did not impose itself on the image; it bent to it.

His celebrated series Paris de nuit does not simply document the city’s nightlife. It constructs an imaginary. A parallel Paris where prostitutes, workers, lovers, criminals, and flâneurs coexist under an ambiguous light that flattens social hierarchies. Night, in Brassaï’s photographs, does not judge or explain. It observes. It suspends. It allows figures to exist without the pressure of daytime narratives. In this sense, the night functions as a space of freedom. Not only for the subjects photographed, but also for the photographer himself. By day, the city imposes order, functionality, clear legibility. By night, that order loosens. Forms dissolve, gestures gain density, and photography ceases to be descriptive to become atmospheric. Brassaï understood that night did not demand precision, but presence.

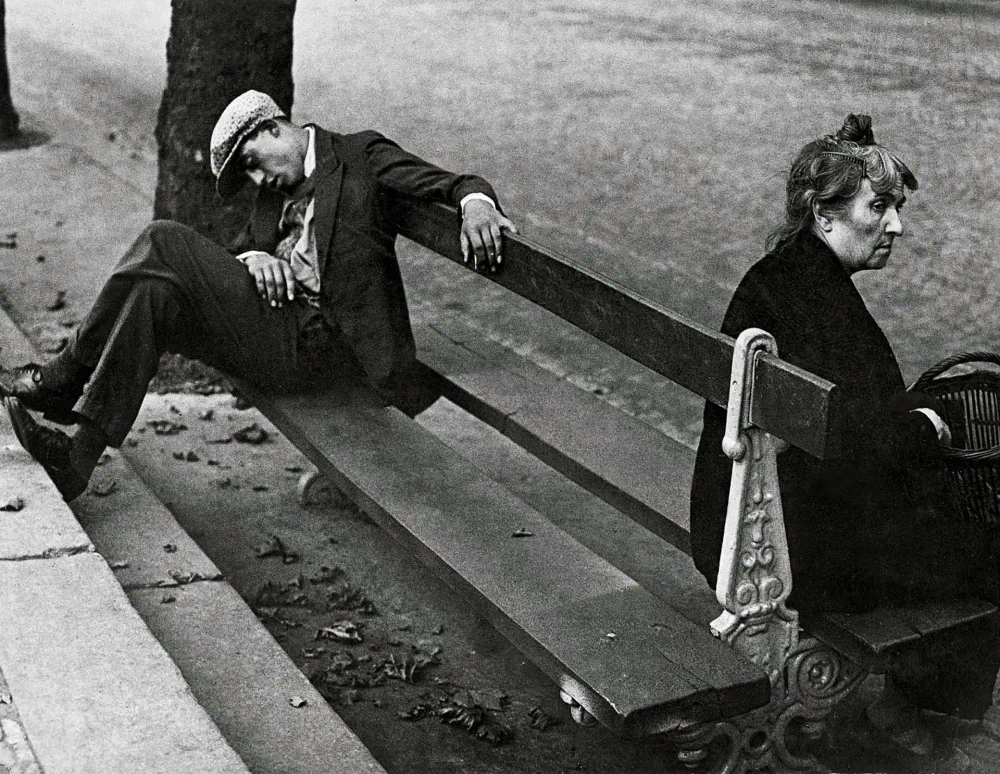

This understanding distances his work from the idea of night as a mere aesthetic device. There is no pursuit of spectacle or easy exoticism in his images. What emerges instead is an intense attention to intermediate states: waiting, fatigue, shared intimacy, accompanied solitude. The night becomes an emotional mirror rather than a backdrop.

Brassaï also understood that the night revealed a different truth about the city and its inhabitants. Not a more authentic truth in moral terms, but a more exposed one. As daytime surveillance fades, behaviors, relationships, and gestures emerge that are not meant to be seen. The camera, far from violating this space, integrates into it with an almost complicit discretion.That complicity is essential. Brassaï did not photograph the night from the outside. He inhabited it. He walked for hours, spoke with people, shared dead time. Photography was not an act of capture, but of coexistence. That is why his images do not convey intrusion, but proximity. The photographer does not interrupt; he remains.

From a formal standpoint, his work establishes a quiet rupture with a more explanatory documentary tradition. Rather than showing, he suggests. Rather than narrating, he evokes. The night allows him to renounce the obligation of total clarity and to accept ambiguity as a value. What is not seen is as important as what appears.

This approach remains deeply influential. Many contemporary photographers working with night, shadow, or low visibility do so within a logic that descends from Brassaï, even when he is not explicitly cited. Night is no longer merely a lighting condition, but a perceptual state. A space where the image is built from the incomplete, the fragmented, and the suggested. In a visual world obsessed with hyperdefinition, Brassaï’s lesson feels especially relevant. His work reminds us that seeing does not always mean clarifying. That photography is not obliged to illuminate everything. That some truths only emerge when we accept shadow, silence, and waiting.

Brassaï understood that the night was not a limitation to overcome, but a language to be learned. And in doing so, he permanently expanded the field of what could be photographed. He did not add a subject to photography; he added a different way of thinking about it. For this reason, his work belongs not only to the history of night photography, but to the history of seeing itself. A way of looking capable of accepting that darkness is not absence, but another form of presence.