To understand Ansel Adams one must begin far from the camera. Not in Yosemite, not in the darkroom, not even in the history of photography, but in a room where a young man practices scales at the piano for hours.

Adams grew up in San Francisco at the beginning of the twentieth century in a family that valued cultural education and allowed this restless child, who did not adapt easily to conventional schooling, to develop an essentially self directed formation. Music was his first serious language. For years he believed he would become a professional pianist, and this was not a passing ambition. He studied rigorously, internalized the logic of musical interpretation, learned to repeat a phrase until intention and result finally coincided.

This experience shaped his character in a lasting way. Music taught him that emotion is not something that simply happens but something constructed through conscious decisions. Sensibility, he understood, requires structure. In music, freedom appears only after technique has been mastered. When Adams abandoned the idea of becoming a concert pianist, he did not abandon that understanding of the world. He transferred it intact to photography.

This musical inheritance explains why Adams never thought of photography as a spontaneous act. From the beginning he understood it as interpretation. It was not about capturing what stood before the lens but translating an experience into an organized visual form. Just as a musician does not merely reproduce a score but interprets it, the photographer must construct an image that responds to an inner intention.

At a time when photography was becoming increasingly accessible, Adams adopted an almost contrary attitude. While others celebrated the ease of the camera, he saw in it a complex instrument demanding the same discipline as the piano. That personal rigor would become the foundation of everything that followed. He did not seek to produce images. He sought to understand how an image might remain faithful to human experience.

This early conception, born from music, allowed him to position himself outside the usual debates of his time. He was not concerned with whether photography should be art or document. The real question, for him, was how to make an image carry the same intensity as what had been lived. That apparently simple question accompanied him throughout his life and would give rise to one of the most influential methodologies in the history of the medium.

Yosemite as a Problem, Not a Setting

The landscape was not his subject. It was the place where photography became an inquiry into experience

Adams’s first trip to Yosemite in 1916 is often described as a foundational, almost mythical moment. Yet to reduce it to youthful admiration for nature is to simplify what truly occurred. Yosemite was not simply a beautiful place he decided to photograph. It was the space where he discovered the insufficiency of photography as he then understood it.

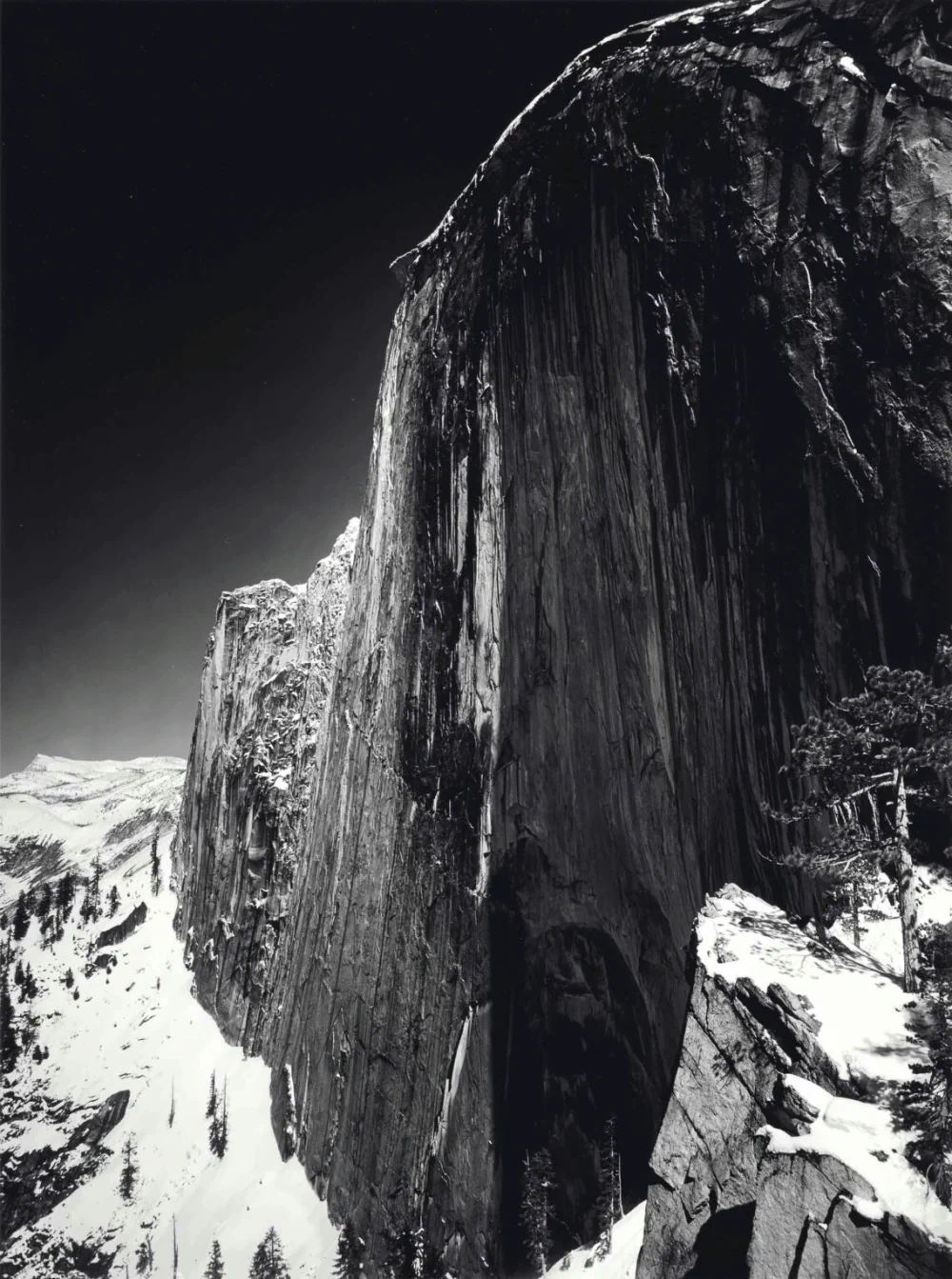

Faced with that landscape, the camera seemed incapable of responding. The images were flat, literal, lacking the emotional depth he perceived while standing there. This initial frustration proved decisive. Adams realized that photography should not merely record appearances but express the experience of being present. Yosemite thus became a laboratory, a territory in which the relationship between perception and representation had to be rethought.

He returned to that place for decades not out of thematic loyalty but because it continued to pose questions. How can one translate monumental scale without falling into spectacle? How can silence be rendered without becoming decorative? How can the complexity of light be made visible without betraying its subtlety?

These questions placed Adams in a singular position within photographic history. While many photographers chose their subjects for narrative or social reasons, he chose an apparently immobile landscape in order to investigate something far more dynamic: the way human perception constructs meaning.

In his work, the landscape is not nature in the romantic sense. It is a relationship between time, light, and consciousness. Each photograph attempts to reconstruct that encounter, not as a copy of the world but as a rigorous interpretation. This distinction is essential. Adams never pursued easy spectacle. His most famous images may appear grand, yet they are built upon restraint, precision, and control.

Yosemite was therefore less a subject than a method. It allowed him to develop a practice grounded in prolonged observation, repetition, and the continual return to the same place until he understood how light reshaped form. This patient work anticipated an idea especially relevant today: that photography is not an instantaneous act but a process of knowledge.

The Invention of a Modern Clarity: Group f/64 and the Break with Pictorialism

Sharpness was not a technical choice but an intellectual position in relation to modernity

In the 1930s photography was still seeking legitimacy within the artistic field. Pictorialism, with its soft focus and manipulated imagery, dominated much of the scene. Many photographers attempted to prove photography could be art by imitating the effects of painting. Adams saw this as a renunciation of the medium’s specificity.

Together with Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and others, he founded Group f/64. The name, taken from a minimal lens aperture, symbolized maximum depth of field and sharpness. Yet this technical decision was in fact an aesthetic manifesto. Photography had to accept its own nature rather than imitate other languages. It had to be clear because its task was to reveal, not suggest.

This defense of clarity coincided with a broader transformation in modern visual culture. In a world rapidly entering industrialization, photography could become an instrument of precise knowledge. Adams understood that modernity did not require more blurred images but more exact ones.

Group f/64 did not aim to eliminate emotion from photography but to relocate it. Emotion should arise from a direct relationship with the world, not from formal artifices. This idea had deep consequences. It freed photography from the need to justify itself against older arts and affirmed it as an autonomous language.

Clarity, for Adams, was never neutral. It was a form of responsibility. To show things precisely was to acknowledge their presence without distortion. This ethical stance toward representation marked a turning point in photographic history and laid the groundwork for practices that would influence generations to come.

Technique as Ethics: The Zone System and the Deliberate Construction of the Image

Control was not mechanical obsession but the necessary condition for honest expression

The development of the Zone System represents one of the most significant moments in Adams’s career. Far from being merely a technical innovation, it was the crystallization of his thinking about photography as a conscious act.

The system divided tonal scale into precisely controllable zones, enabling the photographer to predict the final result with extraordinary accuracy. Exposure and development became intellectual decisions rather than accidents.Adams insisted on previsualization. The photograph had to exist mentally before it was taken. The camera recorded something already conceived. This idea transferred the interpretive logic of music into photography. Just as a musician imagines sound before producing it, the photographer must imagine light before capturing it.

Technique, in this context, was not secondary. It was the means through which intention could become visible. Adams rejected improvisation not because he distrusted intuition but because he knew intuition requires structure to manifest.His work in the darkroom extended this process. The final print was a carefully modulated interpretation, a construction seeking to remain faithful to the original experience. At a time when photography was becoming increasingly democratized, Adams defended a demanding practice that restored reflection to the photographic act.

“The negative is comparable to the composer’s score and the print to its performance.”

Permanence and Relevance: Adams in an Age Saturated with Images

His legacy is not an aesthetic of landscape but a radical proposal about how to look

Today, in a world dominated by the incessant production of images, the work of Ansel Adams acquires an unexpectedly contemporary meaning. His photographs seem to belong to another temporality, one in which looking required stopping, observing, understanding.Visual saturation has transformed photography into an automatic gesture. Adams offers an alternative. He reminds us that an image can be the result of a prolonged relationship with the world. That photography can be a form of thought rather than mere recording.

His influence silently traverses contemporary practice. Concepts such as dynamic range, tonal control, and conscious editing have their roots in his methodology. Yet beyond technique, what endures is an attitude: the conviction that seeing is a responsibility.

Adams did not seek spectacle or constant formal innovation. He pursued something more difficult: a clarity capable of articulating the relationship between human beings and their environment. In doing so he created a body of work that continues to question us. He did not photograph mountains. He photographed the possibility that the act of seeing might remain conscious in a world increasingly inclined to forget it.