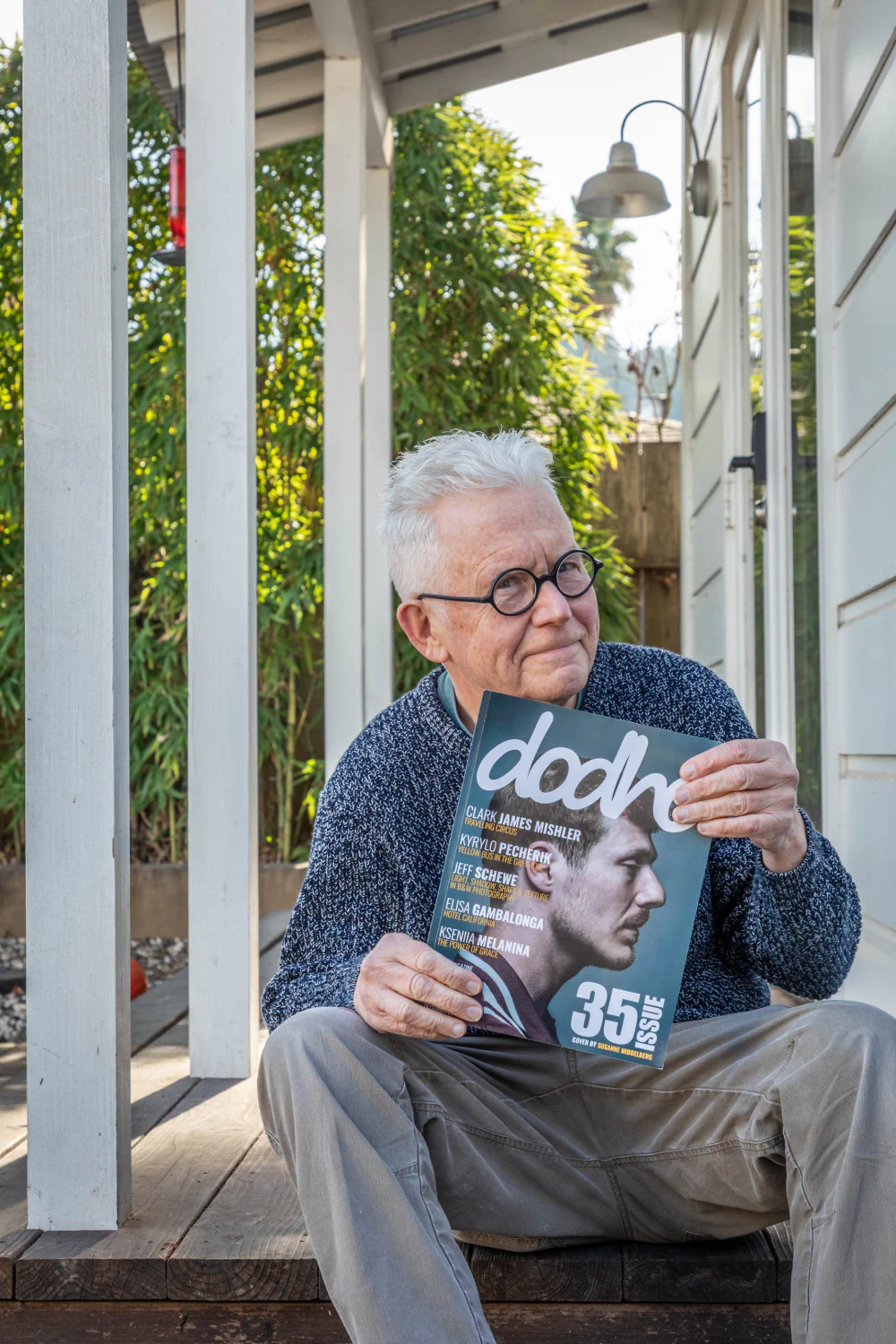

Clark James is one of the featured authors of Issue 35 of Dodho Magazine.

His work is rooted in a documentary tradition based on time, proximity, and sustained observation, where photography becomes a tool for understanding people through their environment, their work, and their shared rituals.

In this interview, we speak with him about the origins of his relationship with photography, the motivations that continue to drive his practice, and his approach to long-term projects. [Official Website] [Official Website]

When did you start to feel that photography became part of your daily life? What led you to choose the camera as your primary means of expression?

Photography became an important part of my toolkit immediately upon taking Photo 101 in college. It was a required class for my design major and ended up being the most important single puzzle piece of my entire education. After twenty years as a successful graphic designer and a great deal of thought, I made the overnight switch from design to photography and never looked back. There were two things I immediately loved about being a photographer.

The first was the fact that I could create hundreds of unique “designs” inside my camera every day. The second thing was that none of my clients ever requested changes! Suddenly, I was having way more fun, creating much more imagery and, surprisingly, I had greatly improved my bottom line. It was around this time that I decided that my camera would never leave my side and that my professional image production and my personal image creation would merge. I also began to understand the necessity of being “on,” i.e., actively looking for “my” images, during every waking moment. It’s been forty years since making my transition to photography and I am still completely in love with the process.

What continues to motivate you to begin new projects? How would you describe your current relationship with photography?

I have always been self-motivated and, from the beginning, imagined myself to be a project photographer. I am drawn to projects that lead to a body of imagery that, collectively, tell a story. Over the years, I have sought and, happily, been hired to document subjects that require more than a day and certainly more than a couple of hours to complete. One photographic story lasted a decade and required twelve segments. I was repeatedly air-dropped into a rural Alaskan Yup’ik village where I documented five generations of a single family involved in subsistence activities.

Being hired to photograph long-term projects is wonderful, but many of my favorite projects were self-created and they never seem to end. My circus imagery is a good example of a multi-year project that will continue to grow as long as the troupe chooses to perform. While some projects never seem to end, I am often unsure when they actually start. I think it is important to photograph whatever pulls you in. And if you continue to be drawn to the subject or activity, I think it important to find new and better ways to tell the story. I have found that the deeper I dive, the better the images get!

How would you define Traveling Circus in a single sentence? What were you interested in conveying that might not be evident at first glance?

My Circus story is a short photo essay documenting the lives of a small troupe of performers who bring their talents and idiosyncrasies to small Northern California communities. I was originally drawn to the mystique of the circus, but I soon realized that this group of unique personalities would provide endless photographic potential and that some of the best images would not necessarily be produced during performances.

What kind of presence did you want to have as a photographer within the circus? What surprised you once you began editing the work? Which part of the circus did you find most challenging to photograph?

As with any documentary project, being a fly on the wall is desirable. After showing up year after year, members of the circus began to feel comfortable with me invading their space. My objective is always to create simple images of real people doing what they do. I think what was most surprising to me was that circus people have little, if any, downtime. To this troupe, the circus is not just what they do but who they are. Putting up the big-top, taking it down, practicing their acts, working on new acts or just taking a few seconds to stretch legs, arms, or back, it’s all circus, all the time. As a photographer, it is a challenge to keep up and to absorb it all.

Was there a moment when the project started to give something personal back to you? When did you feel you had gone far enough, and how did you know it was time to stop?

Documentary photography fills me up; it gives back more than I could ever give. What could possibly be more fun or more fulfilling than hanging with other humans who are living a life completely different from yours and who are more than happy to share their lives with you? Who would ever want such a project to end? For any number of reasons, of course, projects do come to an end, so it’s a good idea to have another idea in the waiting.

I generally have three or four ideas I am photographing at any given time, and I keep my eyes and mind open for the next story to add to my list. I am tired of trying to “sell” story ideas to anyone. For the past decade, I have decided what I should photograph. This self-directed process has been personally rewarding and has even led to similar assignments. I am a big proponent of making images that speak to me. Everything else will follow.

What makes a project deserve continuity over time for you? What do you want to remain from a body of work once it is completed?

I believe a project involving interesting, honest people will be worthy of my time and efforts. The continuity of a good project will always be there for me and, at some point in time, I will have a body of work that hangs together and is much more than the sum of its individual images. With perseverance and a little luck, I may eventually have enough material for a book. For me, the goal is to have fun, learn from the experience and, if possible, earn enough to keep it all moving forward.

Which technical decisions do you make before starting a project, and which are resolved along the way? How does technique influence the type of images you produce?

I am not what anyone would consider a technical photographer and I rarely approach my work with technical solutions. Mostly, I let the subject, circumstances, and light be my guide. I prefer to work quickly and somewhat detached from my subjects so they can do exactly what they do with minimal influences from me. As photographers, we all have very different approaches to our work and, as a result, we all make very different images. We need to be comfortable in our space.

How has the way you evaluate your own work changed over time?

It was Philip Glass who once said: “Getting the voice isn’t hard, it’s getting rid of the damn thing. Because once you’ve got the voice then you’re kind of stuck with it.” I recently realized that the images I make today are similar to those I made fifty years ago. Upon editing black-and-white negatives from the 1970s, I was surprised to discover how unchanged my approach is today. I’m not saying this is a good thing. It is simply what it is.