To speak of Lisette Model is to speak about photography as an act of confrontation. Not confrontation as spectacle, but as position.

Model did not photograph to seduce, to please, or to explain. She photographed to assert a right: the right to look. And more importantly, the right to look without asking permission.

This claim feels uncomfortable today, when photography is increasingly surrounded by ethical frameworks, consent debates, and moral safeguards. Model’s work does not fit easily within contemporary codes of visual politeness. Her images resist justification. They do not apologize. They do not soften their presence. They insist. And in that insistence lies their power.

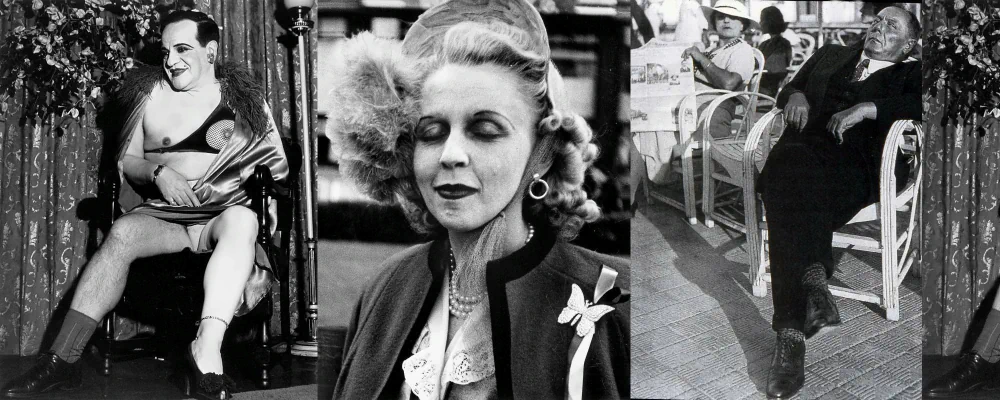

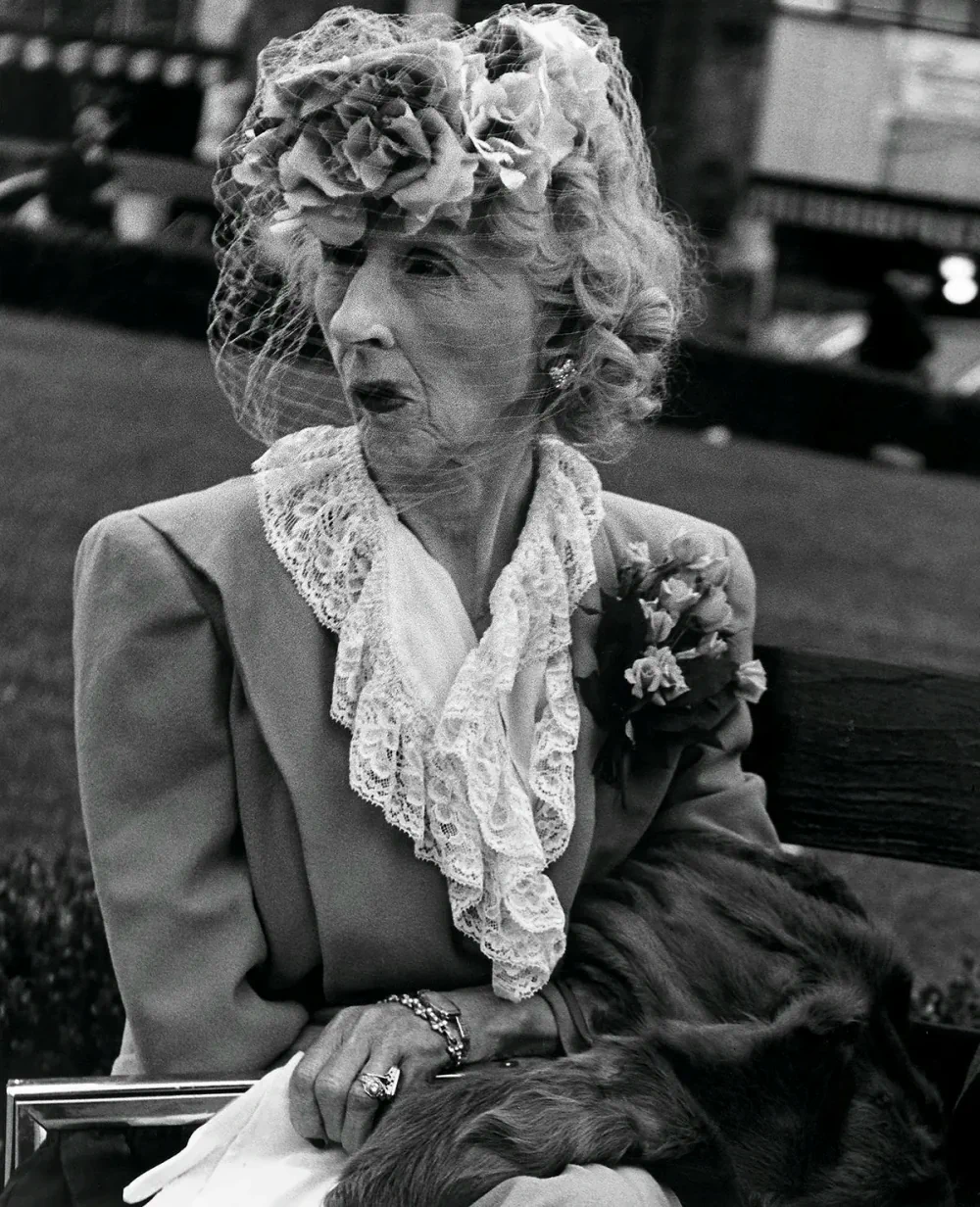

Model’s photography is often described as brutal, direct, unflattering. These labels are not wrong, but they miss the point. What makes her work radical is not its harshness, but its refusal to negotiate visibility. Her subjects are not collaborators in a shared narrative. They are not performers aware of their role. They are people caught in the fact of being seen. The camera does not ask. It claims.

This claim is political, even when the subject appears mundane. To look without asking permission is to challenge the idea that visibility must be granted by the subject. Model reverses the usual hierarchy of photographic courtesy. Instead of requesting access, she asserts presence. The photographer exists in the same space as the subject and does not pretend otherwise. There is no invisibility cloak, no pretense of neutrality.

Model’s proximity is key. She works close, often uncomfortably close. Bodies fill the frame. Faces press against the edges. There is no respectful distance. The camera intrudes, and it knows it intrudes. This intrusion is not hidden; it is structural. The photograph records the tension created by that closeness. The discomfort is not an accident. It is the content.

In series like her street portraits and beach photographs, especially those made at Coney Island, Model refuses idealization. The bodies she photographs are heavy, awkward, aging, exposed. These are not images of leisure as fantasy. They are images of presence as fact. The subjects are not dignified by aesthetic grace; they are dignified by being seen at all, without correction.

This is where the ethical complexity emerges. Model does not flatter her subjects. She does not protect them. She does not offer narrative redemption. The right she claims to look is not balanced by a promise to represent kindly. And yet, there is no mockery. The gaze is not cruel. It is uncompromising.

Model’s photographs expose a fundamental tension in photography: the difference between respect and permission. Respect can exist without consent, and consent does not guarantee respect. Model operates in that unstable space. She respects her subjects enough to believe they can withstand being seen. She does not assume fragility. She does not infantilize. Her work challenges the comforting myth that ethical photography must always be gentle. Model’s images argue the opposite: that sometimes ethics require honesty rather than softness. To look directly, without aesthetic anesthesia, is to acknowledge the subject’s existence without filtering it through approval.

This philosophy also explains Model’s influence as a teacher. She encouraged photographers to abandon prettiness, to reject safe compositions, to trust their instinct even when it felt socially risky. The camera, in her view, was not a mediator of harmony but a tool of clarity. Photography was not there to reassure the viewer, but to wake them up.

The right to look without asking permission is not a license for exploitation. It is a responsibility. Model’s images carry that weight. They do not feel casual or careless. They feel deliberate, intense, committed. She takes full responsibility for her gaze. There is no irony, no detachment. The photographer is present, accountable, exposed.

In today’s visual culture, saturated with images designed to be liked, shared, and validated, Model’s work feels almost shocking in its indifference to approval. Her photographs do not seek agreement. They do not seek empathy through sentimentality. They seek recognition through confrontation. This does not mean her work is timeless in a comfortable sense. It is timely in a disturbing one. It forces us to ask whether our current obsession with permission has diluted the power of seeing. Whether fear of offense has replaced curiosity. Whether photography has become too polite to be honest.

Model reminds us that the act of looking is never neutral. It always carries power. The question is not whether that power exists, but how it is exercised. She chose to exercise it openly, without disguise, without apology. The camera becomes an extension of presence rather than a shield.

Her photographs do not resolve the ethical questions they raise. They hold them open. They refuse closure. And that refusal is essential. It keeps photography from becoming a moral performance instead of a visual inquiry.

To look without asking permission is not to deny the subject’s humanity. It is to accept the risk of encountering it without guarantees. Model’s work lives in that risk. It is uncomfortable because it does not offer safety. It demands engagement.

In the end, Lisette Model does not argue that photographers have the right to do anything they want. She argues something more demanding: that photographers must be willing to stand behind their gaze. No excuses. No moral shortcuts. No hiding behind good intentions. Her legacy is not a style, but a stance. A refusal to dilute the act of seeing. A reminder that photography begins not with the camera, but with the decision to look. And that sometimes, the most honest way to look is without asking permission first.