A few months ago, on a lonely night in Madrid, after spending the entire day patiently and persistently trying to convince a group of executives at a multinational tech company of the need to link process improvement to business goals, I locked myself inside a movie theater.

I needed a mental jolt—something that would force me to think about something different and, at the same time, deeply human. I chose Plan 75, a film by Japanese director Chie Hayakawa. I had heard excellent things about her as a screenwriter and filmmaker, and above all, I was already familiar with the film’s deeply unsettling subject.

The Japanese government had introduced a public health program offering free, voluntary euthanasia. Under this program, anyone over the age of 75 could rely on a panel of experts who would professionally accompany them toward a calm, painless death. The officially stated—and hypocritically benevolent—goal was to prevent the suffering of the final days or years of life, especially for those who find themselves completely alone at its end: a “scientific” way to combat unwanted loneliness. The real objective, of course, was something else entirely, far more dehumanizing and driven by economic logic: reducing the costs of geriatric care and senior living facilities.

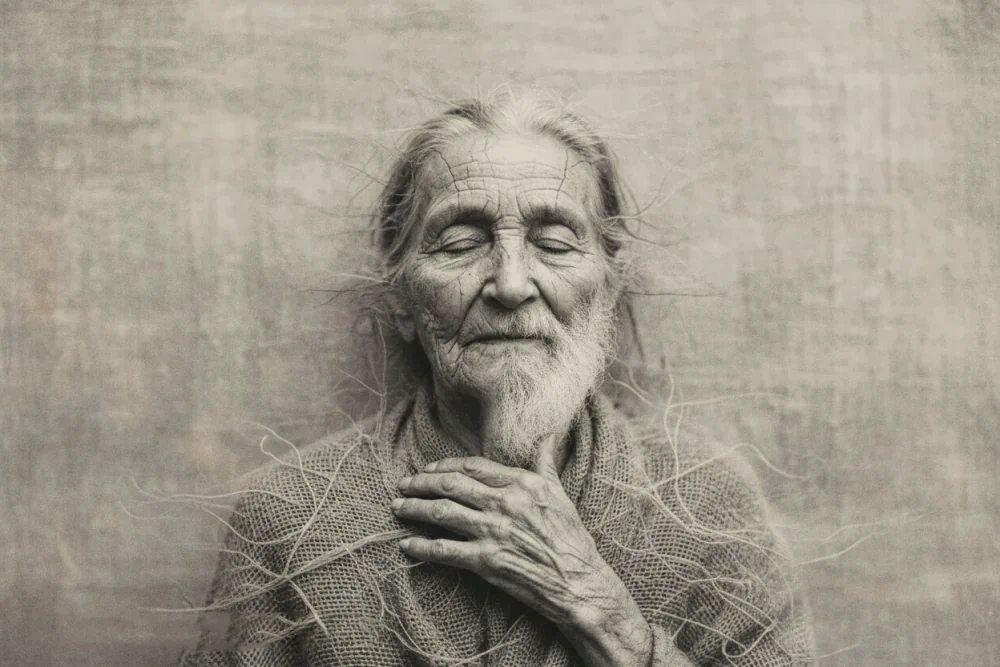

If I pause for a moment to reflect, I find myself asking: “Where has the echo of traditional Japanese lyricism gone? The one in which old age is the twilight of life, its colors simply different, yet no less beautiful than the light of the so-called ‘productive’ years. Has our society really become so dehumanized that we now treat the elderly as a burden, as a cost to be managed?”

It’s true that our society tends to calculate the profitability of everything—even old age. But it’s also true that many elderly people suffer from profound, unwanted loneliness, made even heavier by regret: regret over not having done what they truly wanted, not having lived fully, or having postponed things that ultimately were never realized.

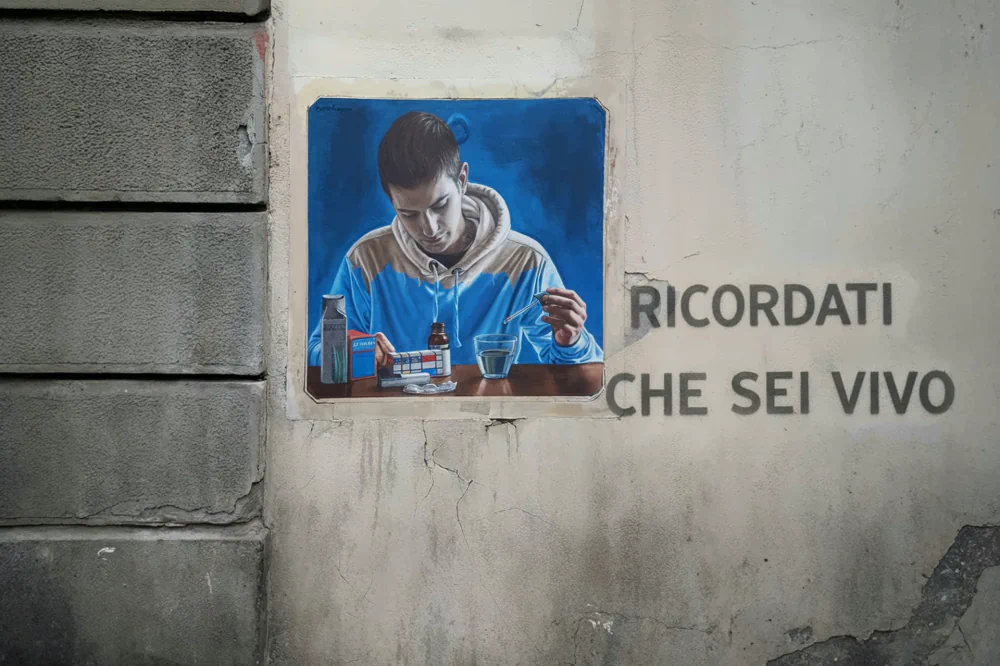

When I got home, still thinking about it, I searched through my photographic archive and came across a photo I had taken in Florence on New Year’s Eve 2023. It showed a wall bearing the words: “REMEMBER THAT YOU ARE ALIVE.” I find it compelling to connect that graffiti with Hayakawa’s film.

If we live—as unfortunately happens more and more in our society—by burying life instead of acting so that death finds us alive; if we live through the lives of others rather than following the traces of our own desires and dreams; if we live a life of escape, of remorse, of unlived dreams and betrayed desires—then perhaps it would make sense for the Ministry of Health to offer us a programmed euthanasia. But why should it come to that? Why don’t we try to live in a way that gives our lives meaning, instead of leaving them at the mercy of chance? Let’s practice wonder.

It isn’t easy. Time is one of the most precious resources we have, and at the same time the one we most often take for granted—only to find ourselves, too late, overwhelmed by regret when it is no longer available. Living fully and consciously in each given moment—the famous here and now—without wanting to be elsewhere and without longing to escape, may be the greatest challenge in any of our lives.

Our minds constantly project us into another place or another time. That is why the real difficulty lies in practicing attention, in learning how to remain present. We must let go of regrets about the past and fears about the future, because both consume the present.

When my son, who has Down syndrome, underwent heart surgery at just five months old to correct a malformation that would have allowed him to live only until the age of five, I was introduced to the world and inner workings of a pediatric intensive care unit. It was a plunge into raw reality and into the present moment—a present in which the angels were the healthcare professionals who offered their skills and humanity in service of the young patients and their families. There, I encountered the purest form of solidarity. There, I lived the selfless desire to do anything possible to ease the suffering of those children, alongside the pain of absolute helplessness when nothing more could be done. It was there that I understood the vital necessity of practicing constant awareness in order to truly live each moment. And it was there that I was given the criteria that have guided me throughout life, helping me distinguish what truly matters from what is fleeting and merely superficial.

By being fully in the here and now, we see things more clearly and act with genuine love—or at least with empathy. This allows us to experience with wonder even things that would normally seem trivial or even tedious.

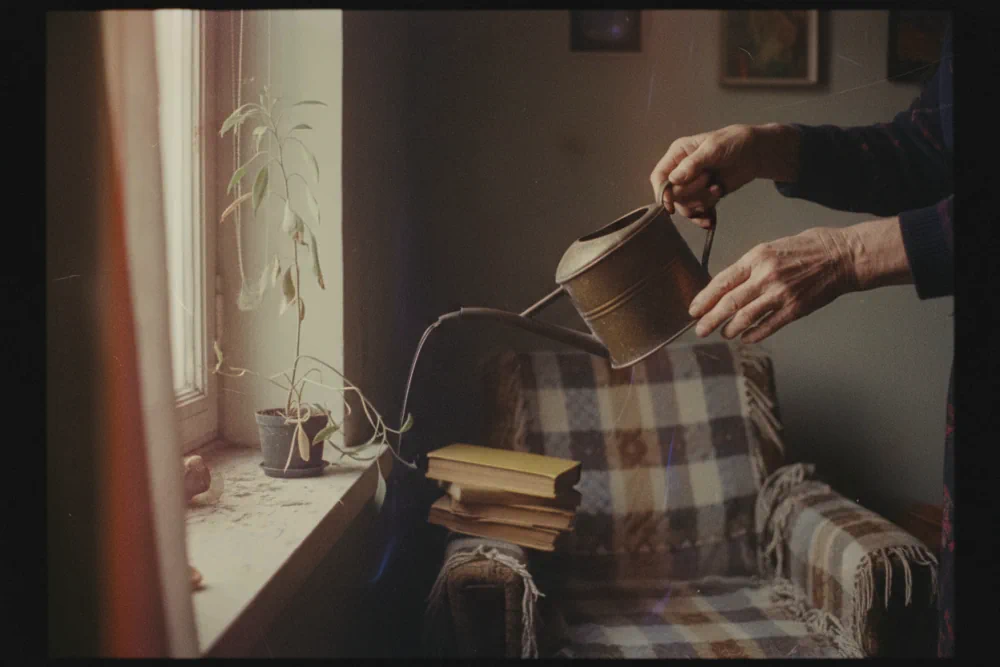

What has been expressed so far about old age and the present moment finds its magical union in the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi—a term that has recently gained popularity in some circles of our society. Wabi signifies stillness, acceptance of reality; beauty is always hidden somewhere. It calls us to recognize the beauty contained in simplicity. Wabi is an attitude that values humility, simplicity, and fragility as a path to true contentment. Sabi is the profound, serene beauty that emerges over time; it is the beauty shaped by time itself, revealed in the processes of use and wear. It is the evanescence of life.

Wabi-Sabi is, therefore, deeply connected to the kind of beauty that reminds us of life’s transience. We must see the world with our hearts; imperfection is the natural state of all things, and in simplicity we find both value and comfort. Wabi-Sabi is a feeling that arises when we sense the imminent disappearance of beauty and life. It evokes a range of emotional responses—from nostalgia and melancholy to reflection and longing.

On the other hand, when all we pursue is the frantic search for happiness, we often find ourselves in a subtle, penetrating state of anguish—one that does not free us from the fear of nothingness or the insignificance of life.

On the contrary, it fuels pessimism, narcissism, and vulgarity. We must cultivate our hearts, put the dignity of the individual back at the center, and start from within—rebelling against superficiality and the vanity of those who make promises they can never keep. This is how life gains meaning, and how we surround ourselves with wonder. In this way, no Plan 75 can hold sway, because we know the source of our own happiness, a reference we can return to whenever we need it, and in doing so, we become truly capable of enjoying our way of being in the world.

Plan 75 reflects an opportunistic and hypocritical approach to old age—one that amounts to ignoring it. It is a mechanism that likely winds its way through many areas of our society. Older people are often marginalized and stigmatized, creating generational conflicts. They are seen as the visible manifestation of human fragility and transience—something we all face sooner or later and strive to eradicate at all costs.

Yet in ancestral cultures, elders were regarded as bearers of wisdom. People turned to them to learn or to avoid mistakes. Their ability to be fully present—without seeking to dominate but instead creating a space where others could feel welcomed and heard—was highly valued.

The ancient Greek philosophers viewed time as a succession of transformations, a continuous flow; Aristotle even argued that time did not exist in absolute terms, but only as the interval between two moments. Time was considered a supreme judge, capable of correcting injustices and redeeming the soul. Perhaps we should return to seeing time—and, by extension, old age—through a similar lens.

Old age can be a period for gathering and reflecting on what has been lived, a time for storytelling, for essence; a time of slowness, of recovery, of openness toward others, and of willingness to be helped. As you get older, you simply are.

Photosatriani

I am a curious of life with idealistic tendencies and a fighter. I believe that shadows are the necessary contrast to enhance the light. I am a lover of nature, of silence and of the inner beauty. The history of my visual creations is quite silent publicly but very rich personally, illuminated by a series of satisfactions and recognitions, such as: gold and silver winner in MUSE Awards 2023; Commended and Highly Commended in IGPOTY 2022/19/18, honorable mention in Pollux Award 2019; selected for Descubrimientos PhotoEspaña (2014), Photosaloon in Torino Fotografia (1995) and in VIPHOTO (2014). Winner of Fotonostrum AI Visual Awards 2024. Group exhibitions in: Atlántica Colectivas FotoNoviembre 2015/13; selected for the Popular Participation section GetxoPhoto 2022/20/15. Exhibitions in ”PhotoVernissage (San Petersburgo, 2012); DeARTE 2012/13 (Medinaceli); Taverna de los Mundos (Bilbao); selected works in ArtDoc, Dodho, 1X. A set of my images belongs to the funds of Tecnalia company in Bilbao, to the collection of the "Isla de Tenerife" Photography Center and to the Medicos sin Fronteras collection in Madrid. Collaborator and interviewer for Dodho platform and in Sineresi magazine [Website]