For twenty years before becoming a photographer, I lived inside the logic of supply chains.

My professional life was defined by throughput, flow, and process optimization, always seeking the invisible bottlenecks that slow things down or cause systems to fail.

When I transitioned into documentary photography, I didn’t abandon that way of seeing. I redirected it. Instead of factories, warehouses, and loading docks, I began looking at people, places, and rituals as systems that were fragile, resilient, and human.

In September 2018, shortly after my work in Puerto Rico, I traveled to Varanasi, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, to observe what felt like the most complete system I’d encountered: a city organized around the processing of life, death, and salvation along the banks of the Ganges River.

A month earlier, I had been in Puerto Rico documenting the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Nine months after the storm, in the communities I documented, blue tarps still covered rooftops. They were no longer temporary fixes; they had become permanent architecture of neglect. Families navigated daily life without electricity or running water. By the time September arrived, I wasn’t looking to escape that reality, but to reorient myself. I needed to see a place where systems—social, spiritual, and physical—had endured for centuries.

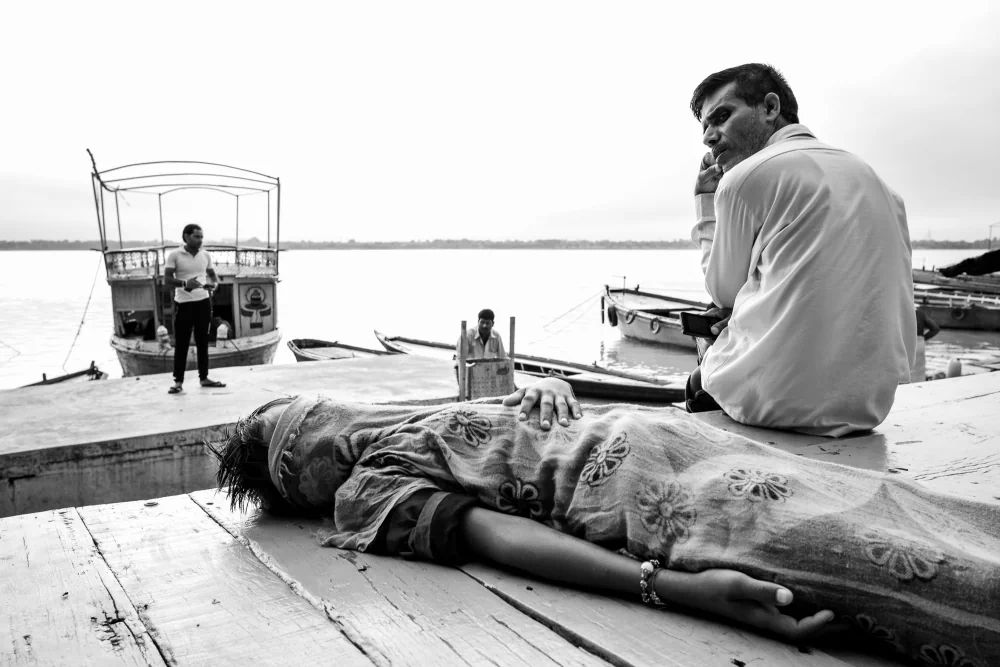

Varanasi had been on my list for years. I was drawn to Shiva, a deity who holds creation and destruction in the same hand. In Varanasi, Shiva’s city, that duality is not metaphor but daily practice. In Hindu belief, Varanasi is a crossing point where death breaks the cycle of rebirth. To die here, to be cremated here, is to achieve moksha. That belief shapes the city’s architecture, the flow of bodies, and the rhythms of the riverbanks long before sunrise. It creates a logistical framework for faith as rigorous as any supply chain I managed in my previous career.

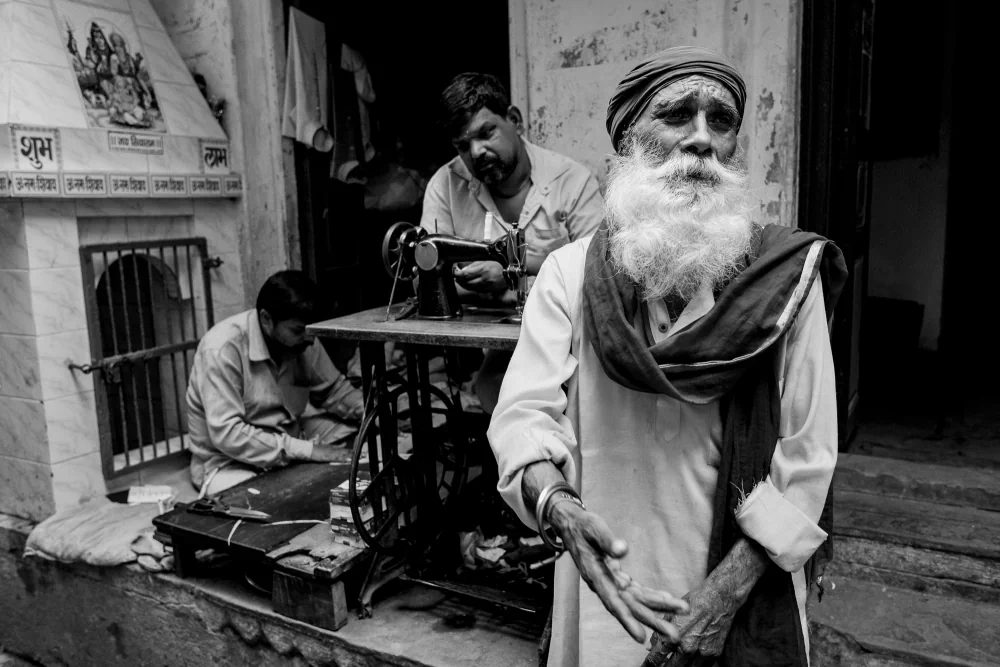

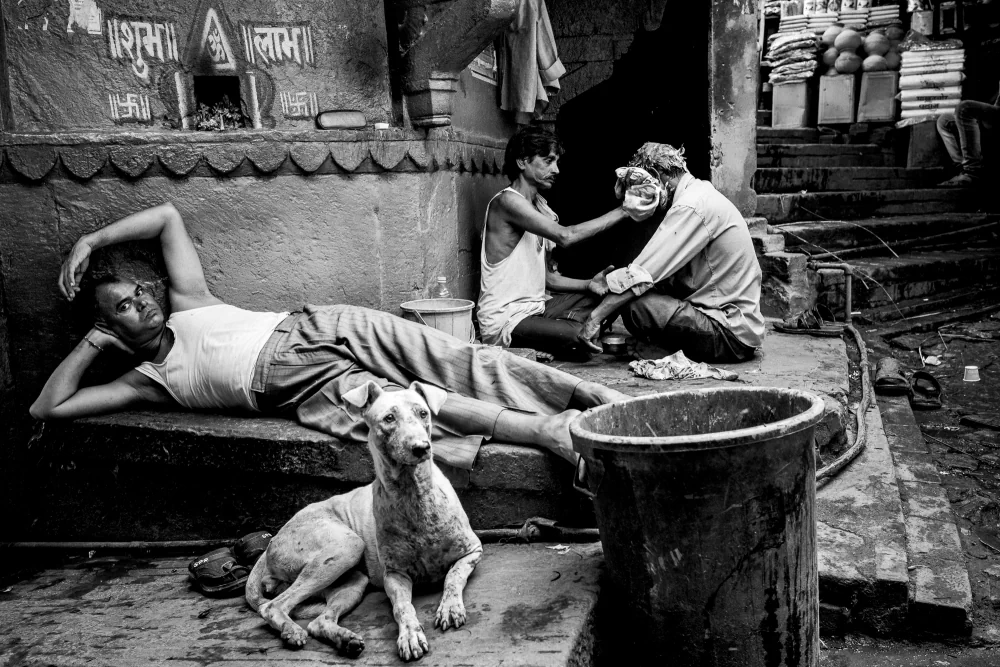

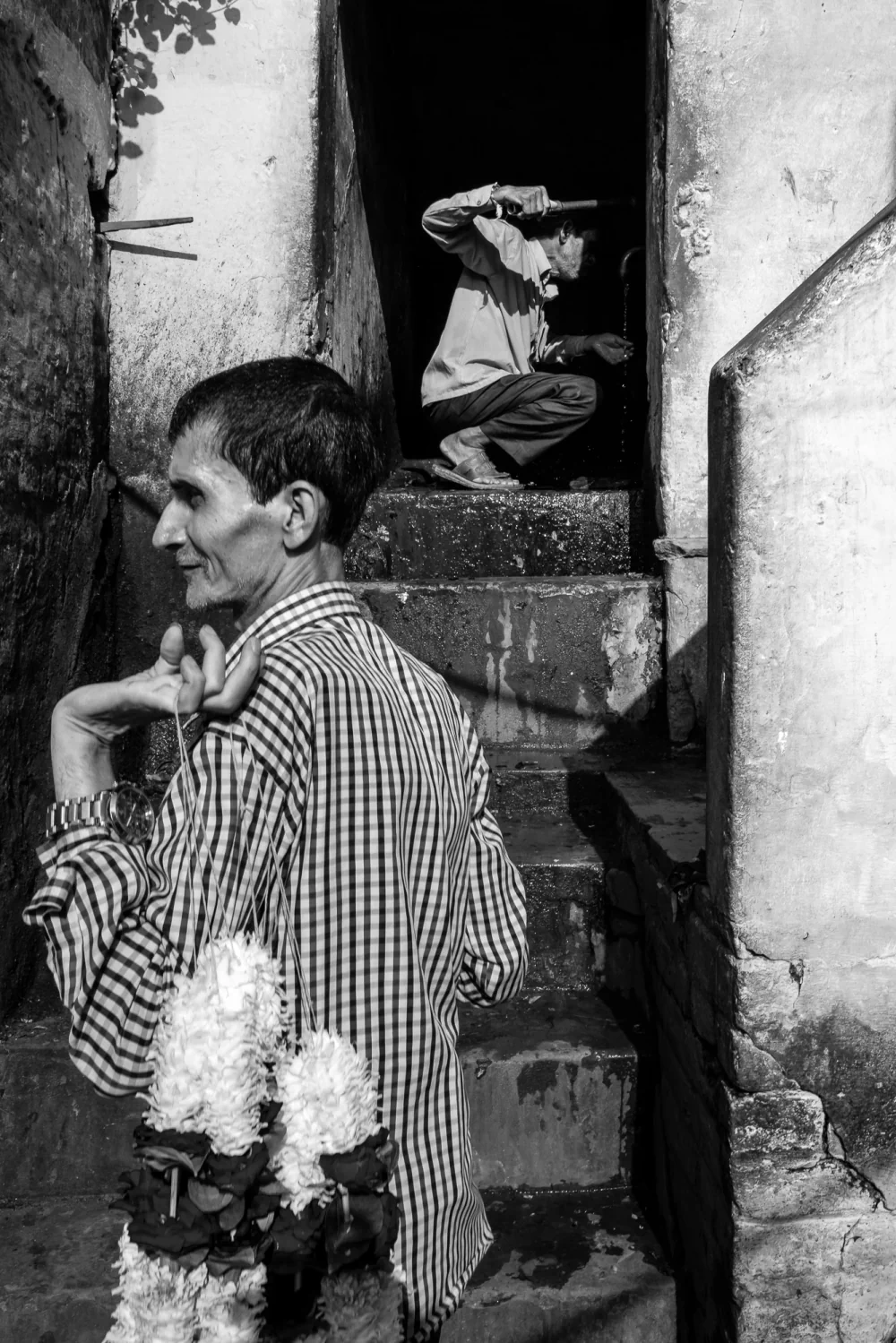

Every morning, the city resets. I began my days early, walking the ghats as light first touched the water. The visual density of the riverbank is overwhelming, yet organized. The rhythmic slap of wet fabric against stone echoed from the water’s edge as women washed saris. Water buffalo cooled themselves in the river. Men bathed quietly while barbers worked methodically, the soft scrape of the blade marking the start of the day. These were not isolated moments; they were interlocking actions that kept the city moving.

The Ganges itself functions as the city’s main artery. From an environmental perspective, the river is in crisis. Yet faith sees something else. In Varanasi, infrastructure extends beyond pipes and filtration plants. Collective belief sustains the river’s role, allowing ritual and routine to continue even where modern safeguards fall short.

Late one afternoon, as the day’s light began to fade, I was walking through the narrow corridors near the burning ghats. I stopped to photograph a quiet scene: a dog beside a man resting on a stone step, and, in the background, a barber completing a shave. Moments later, the sound of heavy footsteps filled the passageway. A group of men moved quickly past me, carrying a body on their shoulders. There was no hesitation, no delay. There was no room for a bottleneck. Whatever needed to happen next had to happen before the sun disappeared. The city demanded throughput, and the people provided it.

I chose to photograph this work in black and white to strip away the noise of the environment. India is often exoticized through its vibrancy—the explosion of color in textiles, spices, and festivals. But color can anchor images to a specific time or trend. Black and white offers clarity. It emphasizes the structural geometry of the ghats, the texture of the stone, and the gestures of the people. It allows these routines, performed in the same rhythm for generations, to exist outside of spectacle. By removing color, I wanted to remove the distraction of the present moment and focus on the continuity of the process.

A figure lies on a wooden platform at the river’s edge, covered in patterned cloth, a bracelet visible on an exposed wrist. A man sits beside them, his back to us, hand raised to his chin, his head turned slightly toward me. Is this how death arrives in Varanasi? Not hidden in hospitals, not sanitized into ceremony, but carried to the river by someone who stays close until the end. I stood there as a witness. I didn’t ask questions.

Morning Rituals is not a travelogue, nor an attempt to interpret belief. It is an observation of how a city functions when destruction and creation are accepted as part of the same cycle. In contrast to my work in Puerto Rico and Guatemala, where I document what happens when infrastructure fractures and systems fail, Varanasi showed me something else: a place that refuses to break.

Each morning, the system resets. And life continues.

About Harvey Castro

Harvey Castro is a multidisciplinary artist and documentary photographer based in Oakland, California, whose work examines systems of identity, displacement, and resilience through long-term, research-driven projects.

His practice extends beyond the photographic print, incorporating cyanotypes on fabric, sculptural elements, and site-responsive installations that reflect the physical and social conditions of the communities he documents. Castro’s projects have been exhibited internationally in museums, galleries, and cultural institutions across the United States, Mexico, and Europe.

He is a recipient of the CENTER Santa Fe Excellence in Multimedia Storytelling Award, a California Creative Corps Fellow, and an alumnus of the Eddie Adams Workshop. His work is developed through sustained engagement and close collaboration, emphasizing presence, process, and the quiet mechanics that shape everyday life. [Official Website]